If disgust is not confined to particular geographical regions, neither is it confined to the perceived savage or the primitive. In travel writing on the Mughal and the Ottoman empires, where, as Ania Loomba has pointed out, “medieval notions of wealth, despotism, and power attaching to the East (and especially to the Islamic East) were . . . reworked to create an alternate version of savagery understood not as lack of civilization but as an excess of it, as decadence rather than primitivism,” disgust persists, albeit differently inflected.

Likewise, in writings on the Mughal court the libidinal and the culinary come to be closely linked. Reverend Terry, whose encounter with the Hottentots is discussed above, had a very different perception of food and the foreign in the Islamic East. Yet ugly feelings are common to both ethnographic experiences. In a passage on the monarch’s private realm he chronicles in detail the fine culinary preparations for which the court is renowned. But Terry’s discussion of the culinary pleasures of the court is framed by his salaciousness at its sexual excesses:

There lodge none in the Kings house but his women and eunuches, and some little boyes which hee keepes about him for a wicked use. Hee alwayes eates in private among his women upon great varietie of excellent dishes, which dressed and prooved by the taster are served in vessels of gold (as they say), covered and sealed up, and so by eunuchs brought to the King. He hath meate ready at all houres, and calls for it at pleasure. They feede not freely on full dishes of beefe and mutton (as we), but much on rice boyled with pieces of flesh or dressed many other ways. They have not many roast or baked meats, but stew most of their flesh. Among many dishes of this kinde He take notice but of one they call Deu Pario made of venison cut in slices, to which they put onions and herbs, some rootes, with a little spice and butter: the most savorie meate I ever tasted, and doe almost thinke it that very dish which Jacob made ready for his father, when he got the blessing.

The dish in question, what Terry calls “Deu Pario,” was in fact, dupiyazah, a dish that continues to be a staple of Mughlai cuisine on the Indian subcontinent. Terry’s pleasure in partaking of it is apparent. He appears to relish the seasoning, the spices, and the meats, the extolling of which culminates in his description of “Deu Pario” as a preparation of biblical proportions. But the general air of degenerate consumption in his description is unmistakable. The king’s women, his eunuchs, his boys kept about for “a wicked use” frame this vignette of culinary indulgence. If Terry’s readers are to join in the pleasures of Mughal cuisine, they are also to deplore its sexual licentiousness. Terry’s travelogue seems intent on presenting the culinary and the sexual together as evidence of a regime that is hedonistic in the extreme.

Also read: East India Company sent a diplomat to Jahangir & all the Mughal Emperor cared about was beer

Among the travelers most willing to partake of the bizarre foods of the Mughal court and immerse himself in its unfamiliar food-related rituals is the Italian runaway Niccolao Manucci. As Jonathan Gil Harris puts it, Manucci’s travelogue is a “foodie’s dream.” In his characteristic playful tone, Manucci devotes long passages of his Storia do Mogor to his gastronomic experiences. In such passages, we see a range of affective experiences from pleasure to disgust to shock. While traveling through Surat in the late seventeenth century, for instance, Manucci suddenly notices everyone spitting blood. When he enquires of a female English acquaintance whether the people of the town suffer from a malady or from broken teeth, she clarifies it is their habit of consuming the betel leaf and invites him to share one with her. Manucci gladly accepts the paan, but the taste has him in such shock that he swoons, faints, and has to be treated with smelling salts:

Having taken them, my head swam to such an extent that I feared I was dying. It caused me to fall down; I lost my colour, and endured agonies; but she poured into my mouth a little salt, and brought me to my senses. The lady assured me that everyone who ate it for the first time felt the same effects.

In the schema of contempt-disgust that we have seen at work in travel writing on the Hottentots and others, Manucci’s physiological response here seems atypical. As such, it appears to be neither contempt nor disgust, sim- ply shock brought on by his distaste for paan. But as I have pointed out earlier in this chapter, it is important to note the word “disgust” as drawing its origins from the Latin dis- and gustus (“distaste”). This etymological connection signals the connections between the traveler’s experience of both distaste and disgust. In marking the distaste of food, the traveler expresses a kind of “good taste,” a qualitative judgment.

Also read: No one could see Shah Jahan eat. But a Portuguese priest once snuck in and here’s what he saw

Manucci’s distaste and disgust become most apparent when he has to dine with the envoys. In a particularly vivid passage he presents a scene of men with food-stained mustaches, digging into the flesh of camels with their bare hands, begging for more fat in their already greasy food, and concluding the meal with their “eructations” as loud as bulls:

Almost every day that I went there I was obliged to dine with the envoy, and I thus had the chance of observing their mode of eating. . . . The food was flesh of camels and of horses cooked with salt in water, and some dishes of pulao of goat’s flesh. The cloth, spread upon a carpet, was very dirty. . . . It was disgusting to see how these Uzbak nobles ate, smearing their hands, lips, and faces with grease while eating, they hav- ing neither forks nor spoons. . . . Mahomedans are accustomed after eating to wash their hands with pea-flour to remove grease, and most carefully clean their moustaches. But the Uzbak nobles do not stand on such ceremony. When they have done eating, they lick their fingers, so as not to lose a grain of rice; they rub one hand against the other to warm the fat, and then pass both hands over face, moustaches, and beard. He is most lovely who is the most greasy. . . .”

In the many travelogues discussed above, we get few opportunities to observe their transformation, their affective responses to the foreign travelers in their domains, and their own sense of disgust at the outsiders’ dietary practices and foodways. For the most part, as Singh observes of Reverend Terry’s narrative, the traveler plays the part of ventriloquist, offering us little by way of his subjects’ motives, feelings, or reactions.

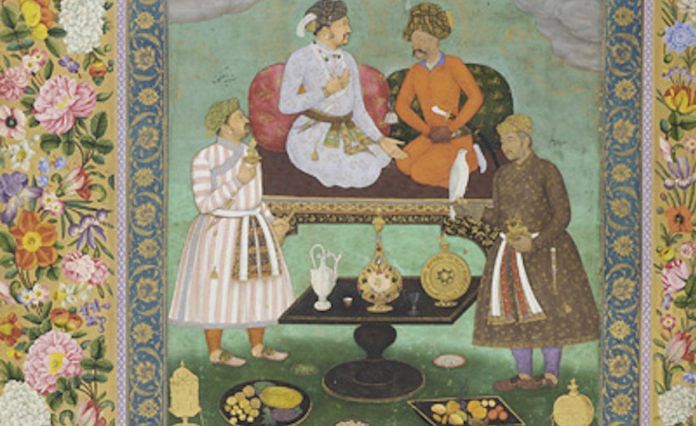

The example I wish to consider here is a shared meal between an English traveler and a Mughal official. The traveler in question is Sir Thomas Roe, King James’s ambassador to the court of Emperor Jahangir. An employee of the East India Company, Roe traveled to the Mughal Court from 1615 to 1619 to secure trading rights in the region. Despite his official title as King James’s ambassador, for all practical purposes he was an employee of the fledgling (and often parsimonious) East India Company, sent on a mission to secure trading privileges for English factors in India. But with nothing of worth to offer the Mughal emperor, Roe’s part-diplomatic part-mercantile task had become virtually insurmountable. In his letters to company officials, he begged them to send more valuable objects to India. “The presents you have this yeare sent are extremely despised by those [who] have seen them,” the ambassador complained.

Though newly arrived, Roe was painfully aware that without presents he had little hope of advancing himself in the ranks of Mughal bureaucracy. For “it is neither person, quality, commission that will distinguish an ambassador,” he wrote in the letter, “but only presents; for which I am worst furnished, having nothing at all.”

This sense of inadequacy set the tone for Roe’s embassy in Jahangir’s court. With little to offer, he resented the gift-giving culture of the Mughal court. His embassy had brought too little and too late, in a land where cross-cultural trade had thrived for centuries before the English arrived on the scene. His meager gifts became a constant source of tension between him and the Mughal monarch. Nearly every object that changed hands between them—maps, paintings, fabrics, coaches—came to be vested with competing territorial and cultural claims. In these “gifts gone wrong”—to use Natalie Zemon Davis’s terminology—we catch a glimpse of some of the earliest encounters between two monumental civilizational entities in the Anglo- Islamic world. The hierarchies at work between East and West in this context do not consistently conform to the frameworks Said identifies in a post-Enlightenment context. While the “body of ideas, beliefs, clichés, or learning about the East” that Said defines as “Orientalism” had yet to be codified as such, Roe appeared to be grappling with the categories of difference that would preoccupy later travelers to the East.

Also read: India was a land of dharma but Europeans reduced it to Hinduism, Islam. And we accepted it

Food, as always, played a key role in defining the terms of etiquette in this encounter. As with gift giving, Roe was frequently confounded by the culi- nary and commensal etiquette he encountered at court. For the most part, he found the many food-related rituals he encountered tiresome. In an irate journal entry he complained about the twenty melons that had been sent to him as a present by an official: “Doubtlesse they suppose our felicitye lyes in the palate, for all that ever I received was eatable and drinkable—yet no aurum potabile.” While the potable gold that Roe had wished for never comes his way, a much sought-after invitation to dine with Mir Jamaluddin Husain finally arrives. Roe gladly accepts, hoping to benefit from the strategic alliance with an important official at court. Thus the meal is planned in the king’s gardens, an elaborate tent is erected, and a banquet is prepared. But after several warm exchanges, when a cloth is laid out and dinner is brought, Jamaluddin begins to retreat from the scene so he can eat with his own people.

Roe becomes painfully aware that their rituals would not permit them to dine with him, “they houlding it a kind of uncleanness to mingle with us.” He feebly objects: “Whereat I tould him hee promised wee should eate bread and salt together: that without his company I had little appetite. Soe hee rose and sate by mee, and wee fell roundly to our victuals.” After his host politely agrees to dine with him, Roe goes on to describe the many fruits and nuts that were served as part of the banquet, but reveals that another guest that same evening confessed his countrymen would take it amiss if they ate together.

In many ways, the archive limits our access to the responses Roe evoked in his guarded host. Since we hear these voices only as Roe channels them, we never get the full range of their affective resonances. Yet we sense that Roe here represents the polluting object. The traveler, as outsider, perhaps poses the greatest danger to the rituals of purity associated with food preparation and food consumption. While this is only hinted at in Roe’s travelogue, we might begin to imagine what such a potential for disgust from the object of disgust implies for other cultural encounters chronicled in the travelogue.

This excerpt from Tasting Difference: Food, Race, and Cultural Encounters in Early Modern Literature by Gitanjali Shahani has been published with permission from Cornell University Press.

This excerpt from Tasting Difference: Food, Race, and Cultural Encounters in Early Modern Literature by Gitanjali Shahani has been published with permission from Cornell University Press.

Very interesting I would like to get more information on food from Tamilnadu and North Karnataka.