Charandas Chor took the Fringe by storm. This play in Chhattisgarhi, performed for an audience who had no access to the language, moved people profoundly. Newspapers, critics and audiences waxed ecstatic over the production: Never before in the history of the Fringe has The Scotsman newspaper awarded its much-coveted Fringe First prize in the middle of the first week, but the Naya Theatre company of India broke that convention. It took an award for its triumphantly exuberant production, Charan the Thief, a performance of such vitality and interest that the official festival made clear its own wishes to honour the company.

Another rave declared, ‘It is a coup for the Fringe to have introduced them to European audiences.’ Reviewers described it as ‘a life-affirming event’, ‘a kind of theatre, at once sacred and profane, totally accessible as spectacle and resonant with political and private meanings.’ Charandas Chor had leapt over the language barrier to capture the hearts of Fringe audiences: ‘Afterwards, when the bows and encore were over, a small boy behind me turned to his mother and said fervently: “I would like to go on stage and see them and shake hands with them all.” There could, I thought, have been no greater tribute.’

I saw the extent of this impact firsthand in 2005. The Prithvi Festival that year was showcasing Complicite’s Measure for Measure from the UK. When we told Simon McBurney, a globally celebrated director, that Habib Tanvir would be attending his play, he excitedly asked to meet with him. He was thrilled to get the opportunity to meet the director of the incredible Charandas Chor, which Simon had seen as a young theatre person attending the Fringe in 1982.

Local Roots, Global Footprint

Habib Tanvir had created a theatre entirely in the Chhattisgarhi language, with Chhattisgarhi actors, which could communicate with the world both powerfully and with ease. How had this happened? To understand this, we need to explore the process by which Naya Theatre productions were created.

They were not simply plays directed by an urban, internationally trained director which included rural actors from Chhattisgarh. They grew out of a close engagement with Chhattisgarhi culture, in collaboration with Chhattisgarhi artists. Habib had taken up Charandas towards the end of a workshop in Bhilai, in late 1974. The play had its first ‘show’ at a Satnami occasion in Bhilai, on the open-air stage of the maidan. Satnamis are Dalits who follow Guru Ghasidas, originally a dacoit, who established the dharma— Satya hi ishwar hai, ishwar hi satya hai. Truth is their God.

‘I thought that this play about a thief who does not abandon truth was very much up their street. That’s why Charandas grew in Chhattisgarh, not Rajasthan,’ said Habib. He asked the gathered audience of around 18,000 Satnamis if he could share his rough show of Charandas with them. He treated it as a rehearsal with audience, stepping in to fix blocking, improvising songs from a Satnami book he had and asking the gathered Satnamis to repeat.

Habib went on to work further with the Satnamis on Charandas Chor. He involved a Panthi dance party and choreographed them into the play. He included their symbols—their flag, their chowk—into the anticlimax of the play. He worked with their poets to write songs that reflected his approach to humanity: The folk singer generally writes in a reformist vein. I said to the poets, Ganga Ram Sakhet and Swaran Kumar, ‘Look, I don’t want to say that lying is bad, give it up, drinking is bad, give it up. I don’t believe that you can change a man unless it happens that he changes himself. Habits are hard to shake off.

So I’d like you to say that just as a drunkard cannot leave drinking, a liar cannot leave lying and a thief cannot leave stealing, truthful men cannot leave telling the truth’ . . . The song worked. The Chhattisgarhi artists owned the play. The language and expression of the play came out of their culture. When they stepped onto the stage to perform, they were in that sense on home soil. Habib, speaking to a Scottish newspaper about the success of Charandas Chor in Edinburgh, had this to say:

I found the actors so full of abandon, so totally lacking in any kind of inhibition in front of a white audience . . . they were totally confident that they were speaking a human tongue to a human audience who could understand it.

They made no difference between this audience and the village audience back home. And there was no difference between their performance in the village where their language is spoken and the one here. And that confidence, that self-assurance and lack of self-consciousness, that enjoyment they themselves get, was almost contagious—that’s what got you. I think this is one explanation; I know of no other.

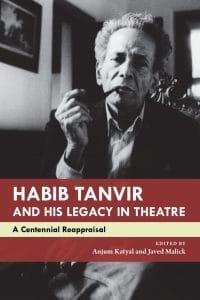

This excerpt from Sameera Iyengar’s essay in ‘Habib Tanvir And His Legacy In Theatre: A Centennial Reappraisal’, edited by Anjum Katyal and Javed Malick, has been published with permission from Seagull Books.

This excerpt from Sameera Iyengar’s essay in ‘Habib Tanvir And His Legacy In Theatre: A Centennial Reappraisal’, edited by Anjum Katyal and Javed Malick, has been published with permission from Seagull Books.

Habib Tanvir belonged to that breed of artists who identified as Muslims but never shone the spotlight on issues prevalent in Muslim societies. Their sole focus was on Hindu society, demeaning and denigrating Hindus for their various social evils ranging from casteism to Devadasi pratha. But Islamic society got a free pass.

In essence, they collaborated with the Mullahs to keep Muslims chained to the 7th century.