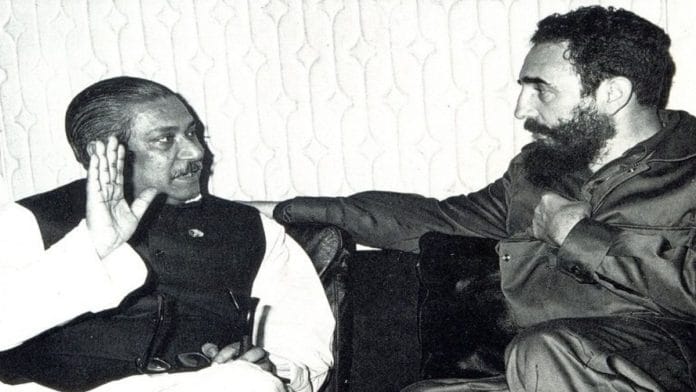

Fidel Castro was right in giving a prescient and timely warning to Bangabandhu that showing magnanimity to his political enemies, who had dourly opposed the Liberation War, would be considered as a sign of inherent weakness in his character and not as a moral virtue. His benevolence would only spur them on to conspire and act with greater gusto and vengeance against him and his government and, in the process, frustrate his dream of building a Sonar (golden) Bangladesh.

Castro was among the few world leaders who had paid the most glowing tribute to Bangabandhu saying he had not seen the mighty Himalayas but had seen Mujib. And yet Bangabandhu paid no heed to Castro’s advice as he thought that by accommodating the committed pro-Pak minded officers in the top echelons of his administration and uniformed services, he had been able to win their trust and confidence.

However, when he started getting hard evidence of how some of his ambitious plans and projects were being sabotaged by an influential section of the bureaucracy, he confided in his party colleagues that he had committed a big blunder by placing repatriates in key bureaucratic posts. He had confessed saying he had tried to build a Bangladesh of his dreams with untrustworthy Pakistani materials and admitted that this was the ‘worst mistake’ of his life.

Castro, being a seasoned revolutionary, who had spent years in the jungle fighting the forces of the ruthless Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista, was a better judge of his political enemies than Bangabandhu. After overthrowing the Batista regime, Castro weeded out from his revolutionary government all those who directly or indirectly were loyal to or supporters of the dictator Batista because he knew very well that by retaining the remnants of the previous regime meant germinating the idea of a counter-revolution.

Castro had drawn lessons from revolutionary history which was replete with instances of revolutionary governments, when ascending power, getting rid, lock, stock and barrel, of defeated forces from their government apparatus as both the victorious and defeated forces could not co-exist and work in the same system under the same umbrella as they were mutually incompatible. Castro had also warned Bangabandhu that he should watch out for CIA machinations as ‘it was out to get him.’

Also read: When the Cabinet approved Emergency—after it had been proclaimed

Already, it was doing everything possible to overthrow a popularly elected government of Salvador Allende in Chile. But an overconfident Bangabandhu took no notice of such warnings as he felt his generous gestures to win over pro-Pak repatriates would help him earn their respect, confidence and loyalty.

Bangabandhu made a series of serious blunders as the repatriates started arriving in Dacca by special flights. He had no fixed policy on repatriates. In fact, his policy differed from person to person. Public attention was focussed specially on three repatriates, the first of whom was Lt General Khwaja Wasiuddin, the only highest ranking serving Bengali officer in the top echelon of the Pakistan Army. In 1971, Lt General Khwaja Wasiuddin was the commander of Pakistan’s biggest infantry corps and had fought against India on the western front but was interned along with his family after 16 December.

But people in Bangladesh were especially keen to know what Bangabandhu would do to A.B.S. Safdar, deputy director general of Intelligence Bureau, Pakistan, who in 1970-71 while based in Dacca was specifically tasked to collect intensive intelligence on Mujib and his associates within and outside the Awami League and submit them to the martial law regime for follow up action. The third repat, Abdur Rahim, a very senior officer of the Pakistan Police Service, was also the focus of public and bureaucratic attention.

This excerpt from ‘Mujib’s Blunders: The Power and the Plot Behind His Killing’ by Manash Ghosh has been published with permission from Niyogi Books.