Those were the times when any female performer-whether they were dancers, singers or even actresses-were looked at with suspicion, as the world of performing arts had become decadent and hit rock bottom. The then high-society women were supposed to strictly be in purdah, let alone sing or dance in front of strangers.

However, several women of high-born status had a courtesan mother with a legitimate father from high society. Akhtari was one such exception. Even so, the British government and its supporters were not very keen to entertain any unmarried female singer.

All India Radio would not admit women unless they were of a respectable stature or, in other words, married. In the late pre-Independence and early post-Independence era in the Indian subcontinent, to be considered respectable, one had to marry and relinquish any connections to their performing past.

By mapping Akhtari Bai’s path in life and music, one can inevitably see the prevalent culture that she was still unable to shake off. Akhtari came to the musical stage when a tawaif singing was still very much a part of the upper-class sociocultural scene in North India. At the peak of her singing and acting career, Akhtari decided to move back to her loving Awadh.

What better place to move to than Lucknow, the social and vibrant capital of Awadh with all its amenities and extravagances? It had its own charisma, the splendour of nawabi culture, sophisticated etiquette and courteous social graces. It was also the abode of the nobles of North India who appreciated and patronized Akhtari’s gayaki, andaaz and ada.

Akhtari Bai bought a property in Cheena Bazaar in Lalbagh with a sophisticated salon in mind. It was an aesthetically appropriate venue for the highest echelon of Lucknow’s societal structure. This house was called ‘Akhtar Manzil’, and in a really short time, it became a popular landmark of the city. This abode rose to fame in the early 1930s and 1940s. The attendees of this salon were the nobility and royalty of Awadh as well as far beyond.

Also read:

Moved by the beauty and charm of Akhtari Bai, Raza Ali Khan could not restrain himself from gracing these mehfils and making her a court singer in the Rampur estate. But even with all the nobility at her feet, Akhtari desired what her mother never had—respect.

In those days, the only way to gain the high society’s real respect was to get married. To this end, she found her partner in the young barrister, Ishtiaq Ahmed Abbasi, a member of the Talukdar family of Kakori. Abbasi Sahab was Lucknow’s foremost lawyer who was popular and respected for his profession and standing in society. He had been educated in London and was a bar-at-law.

His suave looks and polished social etiquette ultimately did strike Akhtari Bai with the Cupid’s arrow. After quite a secret courtship, she married Abbasi Sahab in 1945. The quick ceremony raised the status of Akhtari Bai to Begum Abbasi legally and she became Begum Akhtar for her fans.

Naam Akhtar Tha, Woh Begum, Abbassi, Tarranum unsey tha, Woh Malika-e-Tarranum

(Her name was Akhtar, to him [husband] Begum Abbasi. Melody manifested she was [for admirers], truly the Queen of Melody)

After her wedding, Akhtari moved to Mateen Manzil, Nayagaon, the home of Abbasi’s parents, until he bought a new mansion for his Begum on No. 1 Havelock Road. She strived to transform herself from a public person to a private entity, from shama-e-mehfil baiji to parda-nasheen shareef zadi.

The price of respectability had to be paid-Begum Akhtar gave up music, public performances and her professional life as a concert performer.

This transformation, along with the death of her mother, pushed her into a chasm of melancholy. Since their marriage, Abbasi Sahab had prohibited his wife to sing publicly. After all, she was now an aristocrat’s wife. Begum Akhtar’s mental health went spiralling, but she managed to survive even this extreme depression.

The day was saved thanks to Sunil Kumar Bose, the chief producer of music at the All India Radio in Lucknow, and his tenacious younger colleague, Luv Kumar Malhotra. Luv persuaded Abbasi Sahab to encourage his spouse to sing.

He refused initially but, within 10 years, a declining turn in his fortunes compelled him to let Begum Akhtar perform. Eventually, she returned elegantly to engage in what made her most delighted. Her husband stood next to her in this hour of crisis and encouraged her to restart her radio programmes and music concerts.

She began her life’s second innings with greater commitment and absolute dedication, and once again managed to regain her exceptional status. Her ada and andaz defined Lucknow’s nawabi opulence, she sang with a great understanding of the lyrics and she added far more to the words with her voice. She was now, once again, Mallika-e-Ghazal, Mallika-e-Tarranum and the heartbeat of millions of admirers.

She was awarded the Padma Shri in 1968 and the coveted Sangeet Natak Akademi award in 1972. She continued to garner accomplishments in her lifetime and was awarded the Padma Bhushan posthumously in 1975.

Meanwhile, her husband’s estate was lost partly due to the Partition and partly due to ill management of whatever remained. But, familiar with such changes in fortune, Begum Akhtar relentlessly pursued her career and, some might say, even supported her family.

There is a very touching anecdote that is dear to everyone who knew her. The Begum used to leave a satlarha of tremendous value with the jewellery designer and sitarist, Arvind Parikh, during the off-season. He would, in turn, offer her money to smooth over the lean time. When the concert season started again, Begum Akhtar would give him the money in exchange for the jewellery (which was a present from the Nawab of Rampur).

This system continued for a good seven or eight years. When she passed away, the necklace was with Arvind. The gentleman and musician that he was, he returned it to the late artist’s husband without asking for money in return, as he felt content enough to have been of some help to the legendary singer in her lifetime.

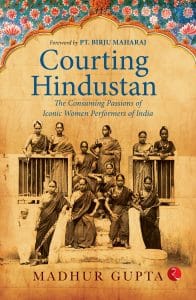

This excerpt from Madhur Gupta’s ‘Courting Hindustan: The Consuming Passions of Iconic Women Performers of India’ has been published with permission from Rupa Publications.

This excerpt from Madhur Gupta’s ‘Courting Hindustan: The Consuming Passions of Iconic Women Performers of India’ has been published with permission from Rupa Publications.