Pai emphasizes the instructive rather than informative potential of history—a strategy similar to that of the nineteenth-century Bengali man of letters, Bankim Chandra Chatterjee. In his historical fiction, Chatterjee sets up the magic, colour and inventiveness of history-as-story against the ‘meaningless jumble of dates and names of persons and places’.

As Sudipta Kaviraj points out, the writing of nationalist history followed two different trajectories: the real and the imaginary. The former was marked by factual research; the latter by a fictive imagination turning to historical subjects. Significantly, at a point when James Mill disqualified ‘oriental fables’ from the domain of rational history, many proponents of rationalism such as Bankim Chandra and Romesh Chunder Dutt combined ‘real’ and ‘imaginary’ histories. The indigenous historian inserted Puranic myths, legends and romances into the historical discourse.

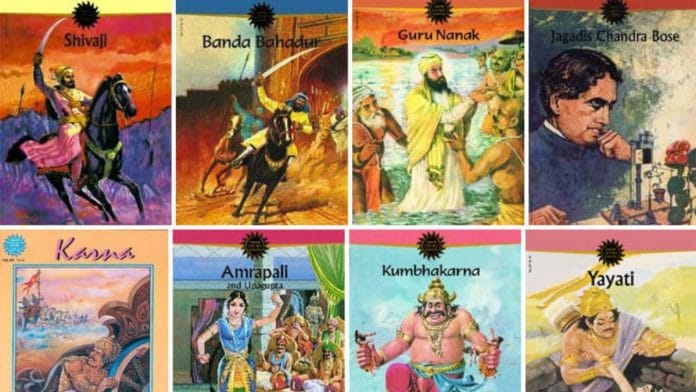

Mimicking the example of Bankim Chandra (and the prominent trend of nationalist history in the nineteenth century), the boundaries of community within the ‘fictional’ history of the Amar Chitra Katha remained fluid and allowed anybody—avowedly irrespective of caste or community—to become a part of the imagined community of the nation. Within this frame, an allegiance to the memory of Padmini’s ‘sacrifice’ or Shivaji’s ‘vanquishment of Muslim invaders’ or the valour of Rana Pratap becomes the touchstone for the patriotism of every Indian, whatever region, caste or community s/he may belong to. A Rajput identity is conflated with ‘Indian’ identity, the history of Rajasthan represents the glorious past of India. To cite from the introduction to Rana Pratap (1977): ‘In essence Rana Pratap’s name is synonymous to the highest order of the revolutionary patriotic spirit of India.’

Exemplifying the triumph of the individual in the most trying circumstances, the ACK’s narratives serve as an elaborate practical guide for modern middle-class children in a competitive, globalizing world. It is difficult to miss the crucial link between the ACK and Pai’s prescriptions for the development of ‘personality’—a term resonant with the modern connotations of leadership and communication skills. This leads me to the Partha Institute of Personality Development, founded by Pai in the 80s. This initiative is far from being as well-known as the ACK, but it is important to trace the contiguities between both projects.

Also read: Tinkle and Amar Chitra Katha, the comics we grew up with that grew up with us

Partha and personality

‘Personality’, in an entrepreneurial, corporate context, connotes attributes such as appearance, enterprise, confidence, ambition and the drive to deal with challenges and succeed. Pai sets up an interesting traffic between history and the discourse of personality development, with history envisioned as a pedagogic tool to teach children how not to fail, and how to be confident citizens in a competitive, individualist world. Emerging on the eve of the 70s, the Amar Chitra Katha had its finger on the pulse of the palpable discontent brewing among the younger generation, faced with the increasing pressures of education and the prospect of unemployment. In addition, there was a rising disillusionment with the iconic figures of nationalist discourse. Pai speaks of the time when he witnessed ‘educated youngsters of Bombay resorting to violence’. He writes, ‘I then met and talked to many youngsters and realized that though today’s education imparts a lot of information to young minds, it does not prepare them to face life.’ Advertisements for enrolment into the Partha Institute of Personality Development appeared in various issues of the ACK, addressing parents in the following manner: ‘The world is becoming increasingly competitive [ . . . ] Is your child prepared for the grim battle of survival and success? Just imparting him the three Rs (Reading, Writing, Arithmetic) is not enough. It is vital that he possesses the three Cs (character, confidence, courage) also.’ A bridge is thus set up between the past and the present, between heroes of the ACK tales and the (globally) successful capitalist entrepreneurs.

“History tells us of many great men who had very humble beginnings. Chandragupta Maurya, who founded the Mauryan Empire was a person of humble origin. Shalivahana, who established a mighty kingdom, was a potter’s son! Kalidasa was a shepherd boy. Sher Shah Suri, who defeated Humayun and became the Sultan of Delhi, was the son of a horse breeder of Sasaram. Hasan, who later became a popular ruler and was known as Bahman Shah, worked on the farm of a Brahmin called Gangu. Shivaji was the son of a petty chieftain.”

In the 80s and 90s, the ACK’s practical middle-class ethic became increasingly geared towards fashioning a global Hindu identity. Pai draws from a range of sources to make this ethic viable and teachable to young people. An ethic resonant with Bankim Chandra’s formulation of ‘anushilan’—seeking the cultivation of innate human faculties, physical and intellectual—animates the ACK’s imagination of an India where the culturally empowered Hindu with a global vision replaces the subject of the welfare state. Pai’s stated claim that education should inculcate courage, patience, perseverance and a sense of fellowship in an individual, skilfully re-notates the four virtues advocated by Bankim as essential for the Hindu male: enterprise, solidarity, courage and perseverance. The ACK narratives also draw on Vivekananda’s reframing of brahminism as a norm of excellence rather than as a status related to the ‘accidents’ of birth or caste. In Adi Shankara (1974), an ‘outcaste’ questions Shankara, refusing to move out of his path as customary: ‘What shall I move? My body of common clay or my soul of all-pervading consciousness?’ Shankara then acknowledges his superiority: ‘He has seen the one reality in all. He is indeed my guru, regardless of his low birth.’

The pedagogic ingenuity of the ACK lies in seamlessly suturing the discourses of Bankim Chandra, Vivekananda or the Gita to that of the popular propagators of capitalist and corporate success in the West—Dale Carnegie and Ayn Rand. It imbues the capitalist worldview with moral authority, teaching modes of cultural leadership to middle-class children that fit in with a corporatized, globalized world and yet remain organically connected with ‘tradition’.

In the Amar Chitra Katha, the implicit critique of welfarism and a plea for individualism is displaced onto a moral plane through the presentation of an ideal evolved self who has a responsibility to society. Drawing on figures such as Vivekananda, ACK ensures that the figure of the ‘economic man’ is not central to its discourse, and it is the duty of the educated upper-caste individual to educate the lower castes. In this manner, the individualist self, imbued with moral authority, replaces the interventionist state.

Chanakya (1971) demonstrates how a ruler must be carefully chosen and trained if he were to lead the nation with requisite power and authority. Chanakya, a celibate sage, trains Chandragupta Maurya to become a mighty ruler. Visually represented as sinewy, muscular and powerful, Chanakya is not a reclusive hermit who meditates in caves, withdrawn from the world. Slighted by Nanda and faced with the invasion of Magadha by Alexander, he chooses Chandragupta—to overthrow the ruler. Chandragupta is anointed to be the new king as he is ‘very brave, very intelligent and very powerful’, with the right amount of respect for brahminical authority and order. Read against the backdrop of the 70s, Chanakya conveys that the ideal ruler must ally himself with the brahminical-patriarchal order.

Notably, Babasaheb Ambedkar, the rallying point for Dalit politics, is also represented in an individualist and Hindu patriarchal mode in an eponymous issue devoted to him (1979). The heroes of the ACK are routinely born at an auspicious hour in the Hindu calendar, signalling their extraordinary destiny. Hindu religious symbols fill the large opening panel of Babasaheb Ambedkar, as an ascetic prophecies Ambedkar’s birth to his father: ‘I bless you. You shall have a son, who will achieve worldwide fame.’

In the course of the narrative, we tour the gamut of Babasaheb’s experiences— the struggle of his family to educate him, his solitary studies at two in the night in the crowded one-room tenement in Bombay, his endless hours of toil at the British Museum library in London. Each event is pressed into re-affirming the power of the individual, never allowing caste to emerge as a social and political question. In the manner of all ACK heroes, Ambedkar is a model of excellence. Most importantly, he emerges as an icon of merit. If we read this in the larger context of the ACK’s valorization of the individual, the story hegemonically recasts the historical marginalization of the lower castes as a condition requiring ‘meritorization’ and self-elevation for emancipation. While Ambedkar’s life and writings are foundational to Dalit politics and movements for reclaiming rights, in the ACK, this figure is deftly displaced on to a discourse that is fundamentally opposed to the special rights that the state is constitutionally obligated to provide to historically disadvantaged sections.

Babasaheb Ambedkar can be situated at the cusp of the cultural politics signalling the transition into the 80s. Significantly, it was republished in 1996 after the violent anti-Mandal agitations of the early 90s and the subsequent resurgence of Ambedkarite politics.

This excerpt from Remaking the Citizen for New Times: History, Pedagogy and the Amar Chitra Katha by Deepa Sreenivas has been published with permission from Seagull India.

This excerpt from Remaking the Citizen for New Times: History, Pedagogy and the Amar Chitra Katha by Deepa Sreenivas has been published with permission from Seagull India.

Academics like Deepa, Sudipta and others of their ilk thrive on the caste system. If Hindu society were to successfully eradicate this evil practice, they would be left with nothing to do.

Their interest is not in exterminating this absolutely horrible practice, but in keeping Hindus divided. If Hindu society successfully overcomes the caste problem it will be a much more united front thereby posing a significant challenge to pseudo-seculars like these academics. Their interest lies in keeping Hindus divided and the best way to do so is to perpetuate the caste system. As long as caste system exists, it will be easy to divide Hindus and pit one caste against another.

The greatest beneficiaries of this will be the aggressively proselytizing religions such as Islam and Christianity.

People like Deepa Srinivas are the reason why there will never be unity in our society. Because they will pull out all stops to ensure that we remain divided into various castes and classes.

The existence of caste in Hinduism is extremely unfortunate. And genuine attempts have been made over the last 300 years to eradicate the problem. To a large extent we have been successful as caste lines in modern India are not as rigid as they used to be in colonial India. In fact, inter-caste marriages are common nowadays.

But the issue with people like Ms. Srinivas and Mr. Sudipta Kaviraj is that this progress is just not acceptable to them. They are worried that if caste were to become irrelevant some day, what would be their own relevance?

Such people – “academics” rather – would write reams and reams about caste but do nothing to fight this social evil. Why? Because they and their “scholarship” remains relevant only so long as this pernicious evil of caste persists in our society.

These vultures feed upn the divisions of Hindu society. In a way they assist the Abrahamic religions like Islam and Christianity to attack Hinduism and convert millions of poor lower-caste people.

No wonder, they see Swami Vivekananda, Sri Aurobindo, Ramana Maharishi, etc. as threats.