Fourteen-year-old Akbar succeeded his father Humayun, under the mentorship and regency of Bairam Khan, who ensured that the young Mughal emperor consolidated his rule in India. Akbar gradually expanded the Mughal empire across a vast area of the Indian subcontinent, and ruled for half a century between 1556 and 1605. The Akbarnama is the official chronicle of his reign in three volumes, of which the third volume is known as Ain-i-Akbari, itself a monumental work.

The Akbarnama is attributed to Abu’l Fazl, one of the highest-ranking intellectuals of his time and the official chronicler of Akbar’s court and reign (Blochmann, 1873). The Ain-i-Akbari reveals that the Caracal was of great interest to Emperor Akbar. The Persian word siyagosh is used for Caracal in the text

The Siyagosh

His Majesty is very fond of using this plucky little animal for hunting purposes. In former times it would attack a hare or a fox; but now it kills black deer. It eats daily 1 s. [seer, 1.25 kg] of meat. Each has a separate keeper, who gets 100 d. [darb, half a silver rupee] per mensem (Blochmann, 1873).

Akbar made significant contributions to the literature of the time. The Ain-i-Akbari mentions that the emperor would have books read out to him every evening. Akbar loved depictions of stories through painting, and commissioned several such works from his court artists. Caracals also found a place in these illustrated texts. The styles of painting, however, “were not innovations of the Mughals, since these were in practice earlier, both in sculpture and painting in India and Persia” (Verma, 1997). The emperor personally took charge of the painting atelier, and his patronage attracted the finest painters to his court. From 1570 to 1585, Akbar hired over one hundred artists, including a good number from Central Asia. Using texts sourced from Sanskrit, Arabic and Turkic literature, luxurious illustrated copies of their simplified Persian versions were created in the royal atelier. Four of the texts, several copies of which were commissioned during his reign – Anvar-i-Suhayli, Tutinama, Khamsa-e-Nizami and Shahnameh (Maurice, 1953) – have many wildlife-centric fables and scenes where the Caracal is prominently depicted. In fact, the Caracal is found in multiple illustrated manuscripts of these four texts, often in the very same scenes.

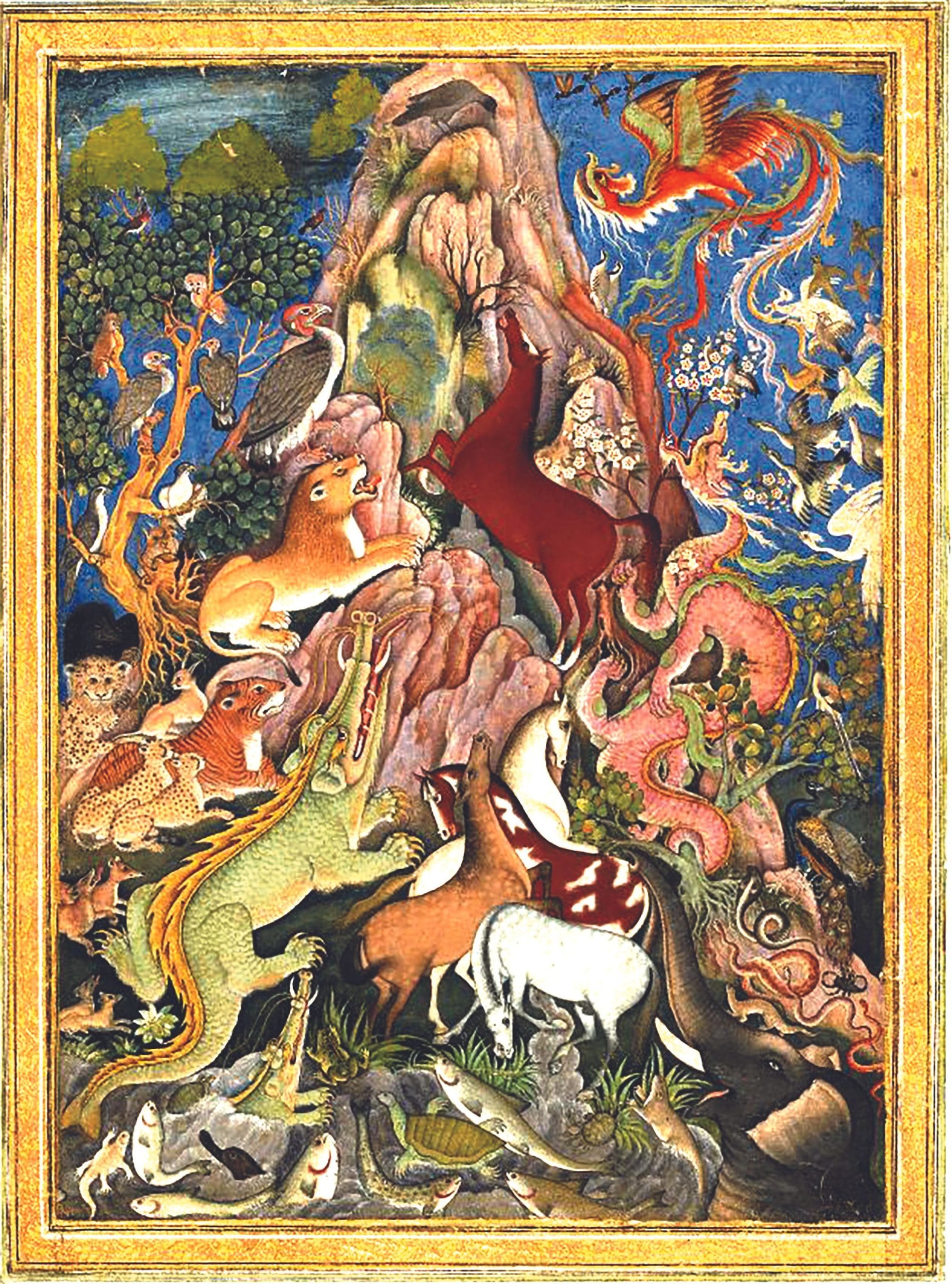

The scene is possibly from a variant of the Anvar-i- Suhayli, or could be an illustration of the Ottoman-era poet Lami’i Celebi’s Serefu’l-Insan, a morality tale in which animals complain of their mistreatment by mankind. A Caracal is present among the vast array of animals, including the mythological simurgh and dragon. Credit: The Trustees of the British Museum, 1920,0917,0.5

Besides the illustrations of stories, a vivid description of the Caracal is found in a classical medieval zoological handbook, the Hayat al-hayawan al-Kubra. Hayat al-hayawan al-Kubra or “The Great Life of Animals” by Damiri (died 1405) was translated from Arabic into Persian in Akbar’s time (Schimmel, 2004). However, in the text, the Caracal is referred to by its Arabic name, “Anak al-ard”, and is described as follows:

It is a certain beast of prey, about the size of a small dog, its chase is considered to be excellent but it sometimes jumps at a human being and wounds him. It does not eat anything but flesh, and sometimes it seizes a crane and birds resembling it, to which it does a good turn. (Jayakar,1906)

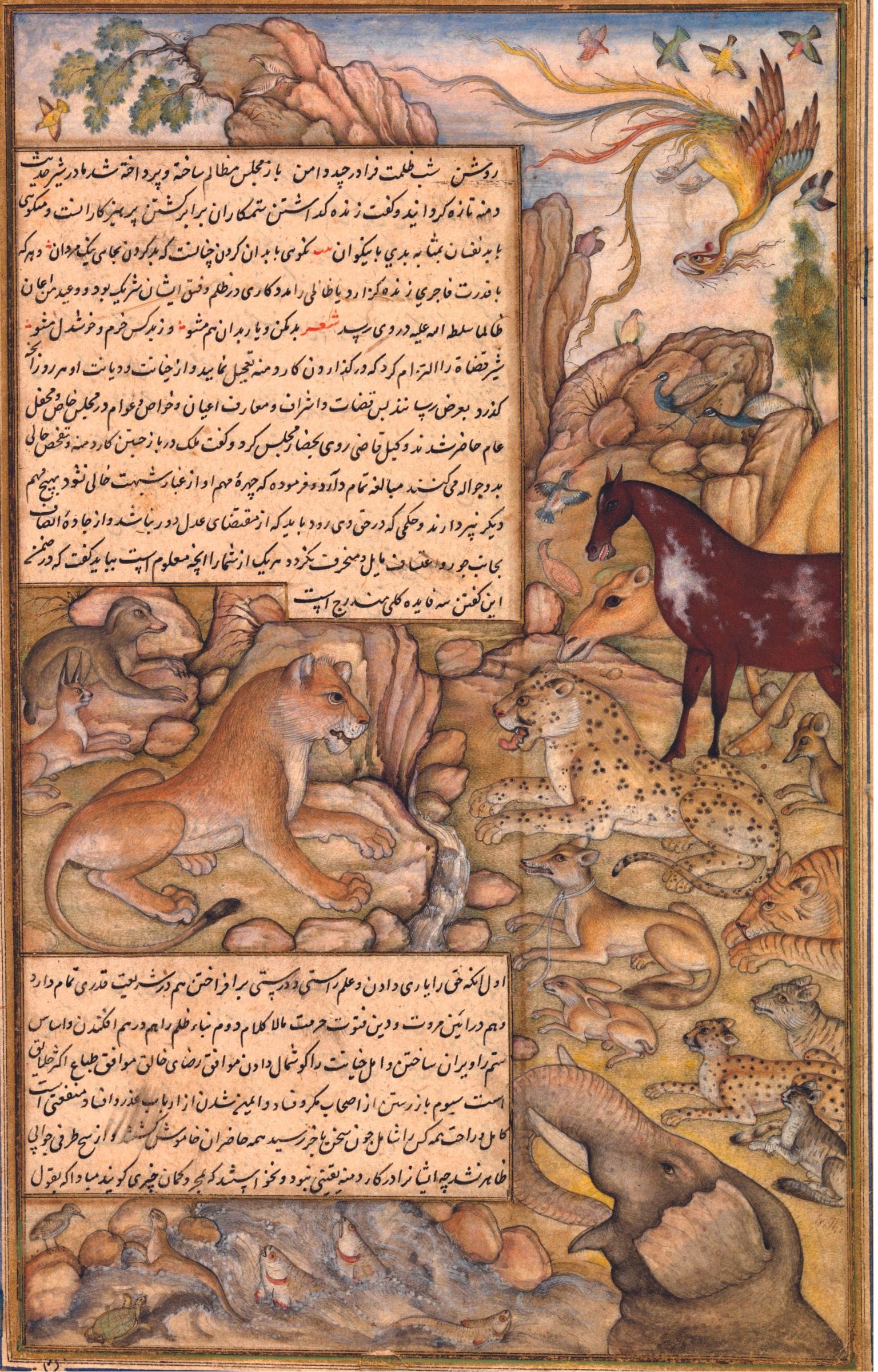

An illustrated scene from the Anvar-i-Suhayli composed by Ustad Hussain Vai’z Kashifi. Among the animals present in the trial of the jackal Dimnah (accused of spreading misinformation) in the lion’s kingdom is a Caracal. Credit: The Chester Beatty, IN O.4.4

Anvar-i-Suhayli

The fables of Anvar-i-Suhayli are based on the ancient Indian collection of interrelated animal fables in Sanskrit verse and prose called Panchatantra (“Five Treatises”) (Contadini, 2007). The manuscripts have depictions of Caracals in the illustrations to some of the stories.

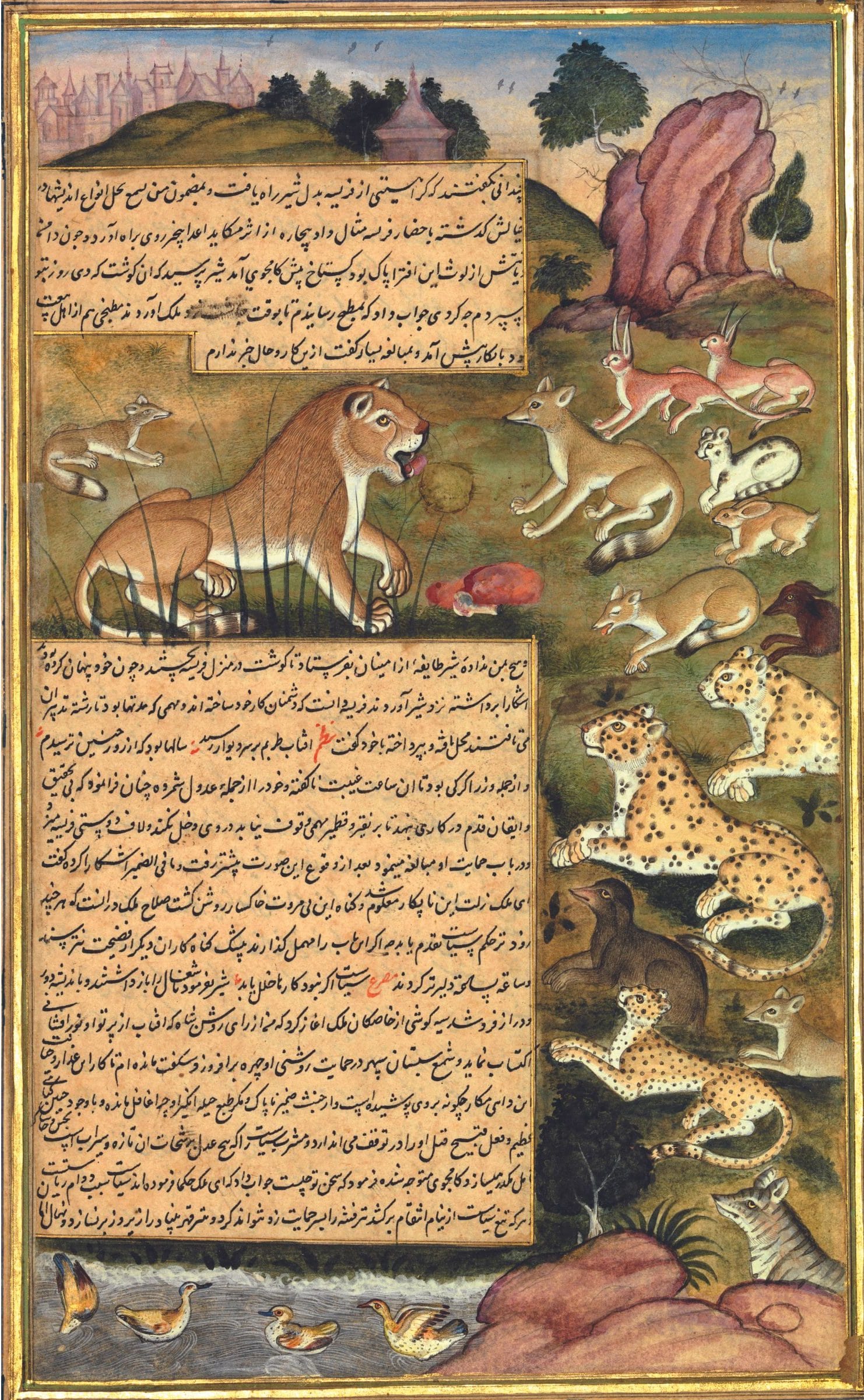

An illustrated scene from the Anvar-i-Suhayli composed by Ustad Hussain Vai’z Kashifi. The lion pardons the jackal Farisah (a minister in his court) after wrongly accusing him of stealing his meat. This illustration was inscribed by the artist Khem Kurd. Also present are a pair of Caracals. Credit: The Chester Beatty, IN O.4.61

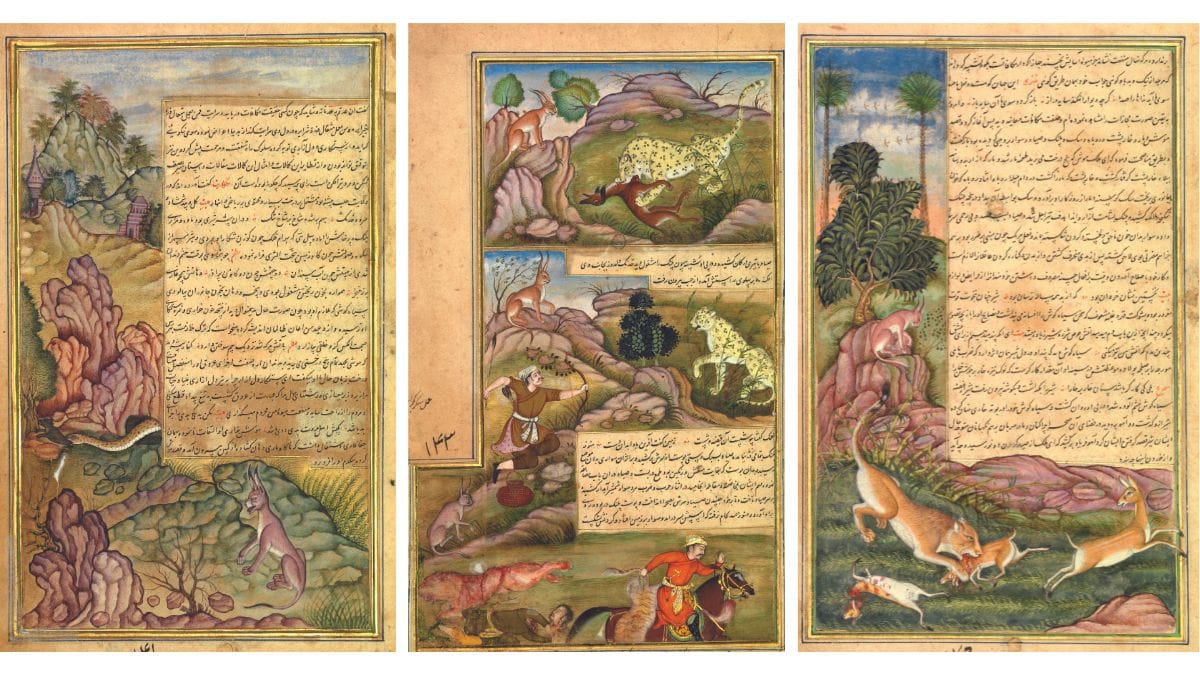

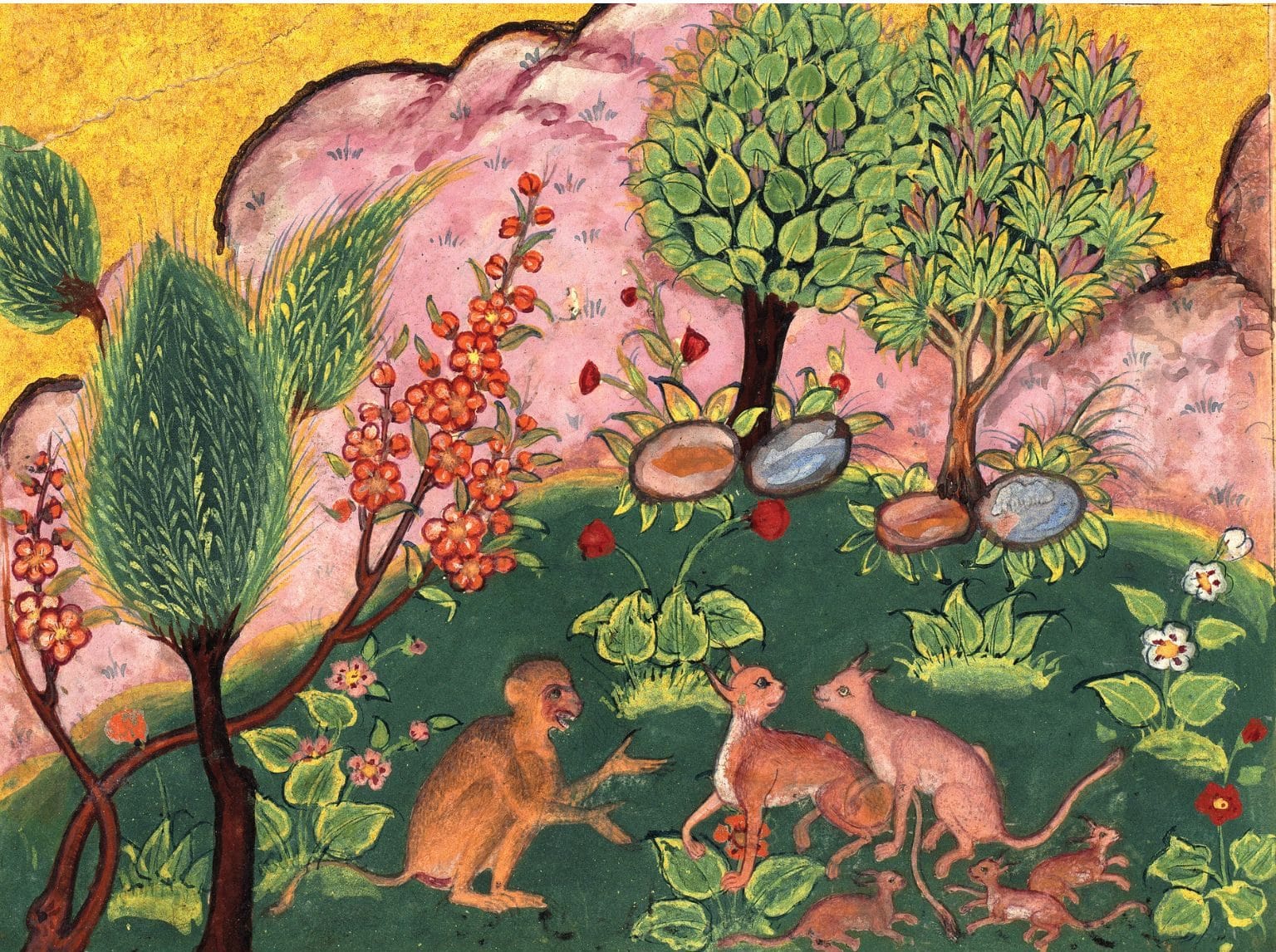

Illustrated scenes from the story of the peaceful minded Caracal from a manuscript of the Anvar-i-Suhayli composed by Ustad Hussain Vai’z Kashifi. This is one of the few adapted stories where the Caracal is not portrayed as cunning or malevolent, but rather as a beacon of morality. The first miniature is painted by Asi in Agra. The second miniature is painted by Nandram Gwaliori and inscribed by Shankar Gujarati in Agra. The artist is unknown for the third. Credit: The Chester Beatty, IN O.464, IN O.463 and IN O.465 (Left to Right)

Tutinama

Relatively early in his reign, Akbar commissioned an illustrated version of the Tutinama or “Tales of a Parrot”, which consisted of 52 fables illustrated by 250 miniatures. The Tutinama was adapted from a Sanskrit anthology called the Sukasaptati or “SeventyTales of a Parrot” from the 12th century AD (Beach, 1992). It was adapted into Persian by Hazrat Ziya’ al-din Nakshabi. The main narrator in the Tutinama is, as its title suggests, a parrot owned by a woman called Khojisteh, and in order to prevent her from conducting an adulterous affair while her husband (a merchant by the name of Maimunis) is away on business, narrates long stories to her in the night. The Tutinama includes many animal-centric fables, including a very interesting story involving a lion and a syagosh (Caracal) (Anonymous, 1801).

As this is a unique instance of the Caracals being major characters in a story, it is worth providing a recounting of the tale here:

A Lion Whom a Syagoash (Caracal) Dispossessed of Its Dwelling

When the sun was sunk into the west, and the moon shone bright, Khojisteh went weeping to the parrot, and said, “I come to you every night for leave, and not for the purpose of hearing you relate tales.” The parrot answered, “No injury can happen to you from my admonition, but you will speedily derive advantage: Go to-night to meet your lover; and if any enemy of yours should come there, I will set on foot a stratagem, as did the syagoash.” Khojisteh asked, “What is the story of the Syagoash?”

“Tutinama (Tales of a Parrot): Tale XXIX”, ca. 1560

First of four illustrations from a manuscript of the Tutinama commissioned during the reign of the Emperor Akbar. Credit: The Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. A Dean Parry 1962.279.193.a.

The parrot said, “In a desert dwelt a lion, who had a monkey for his favourite. It happened that the lion went a journey to some place; previous to his departure he handed over his dwelling to the charge of the monkey. During the absence of the lion, a syagoash took possession of this dwelling- place, because it was a good spot, and chose it for his habitation. The monkey said to the syagoash, This is the lion’s residence, how can you presume to take up your abode here without his permission? The syagoash replied, I have discovered that this place is my paternal inheritance: What news have you? The monkey was silent. The female syagoash said to the male, It is not advisable to continue here; for, to oppose a lion, is to sport with one’s own blood. The male replied, Aye, mistress, when the lion comes, I will drive him away from hence by stratagem. In short, after some days, intelligence arrived that the lion was coming. The monkey went out to meet the lion, and told him all the circumstances about the syagoash, and said, I remonstrated, when he answered, I have discovered that this place is part of my patrimony. The lion said to the monkey, It cannot be a syagoash, how could such an animal usurp my place? It should seem that it is some beast who is stronger than myself. The monkey answered: He is not stronger than you. The lion said, How you talk! There are many animals who exceed me in strength.

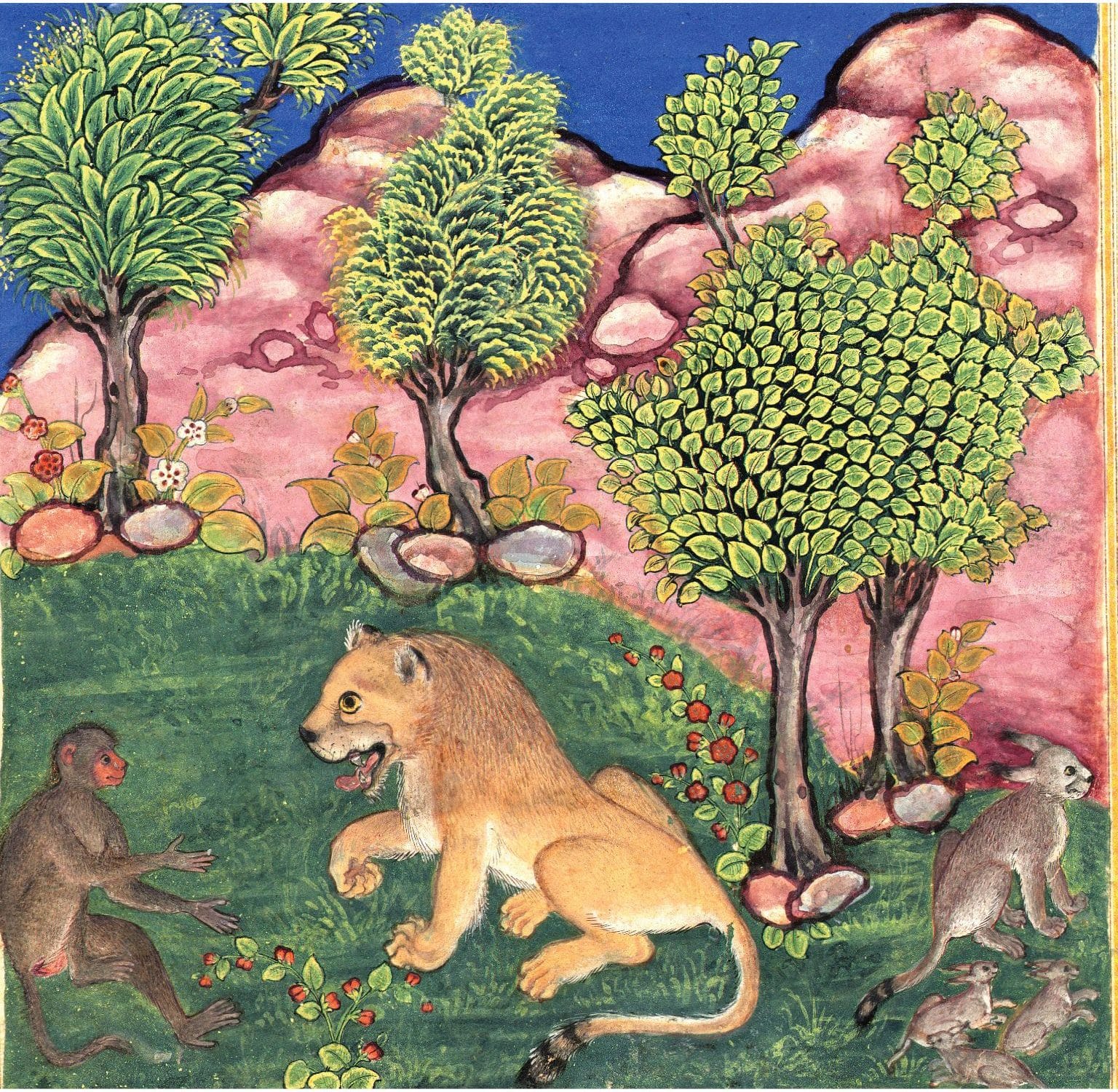

Second of four illustrations from a manuscript of the Tutinama commissioned during the reign of the Emperor Akbar. Credit: The Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. A Dean Parry 1962.279.193.a.

The lion, terrified, set out for his own home, and arrived near the spot. Before the lion’s arrival, the syagoash thus instructed his female: When the lion comes near the dwelling, make your young ones cry; and if I should ask, Why do the cubs cry? you must say, They want fresh lion’s flesh to-day, and will not eat that of last night. In short, the lion approached the dwelling, and the young ones began to cry. The syagoash asked, Why do the cubs cry? The dam answered, Because they are hungry. The syagaosh proceeded, What! is there nothing remaining of the quantity of lion’s and human flesh which was given them yesterday? The female said, They will not eat stale meat; they want some fresh. The saygaosh said to the whelps, Make your minds easy, and have a little patience, I have that our lion will be there to-day; and if this intelligence is true, then, please God, you shall have plenty of fresh meat to devour. The lion was alarmed at hearing those words of the syagoash, not knowing him to be a syagoash. He then fled from the spot, and asked the monkey, Did I not tell you that some mighty animal is in my dwelling? The monkey said, Be not afraid, for this animal is very diminutive, and he speaks these words in order to deceive.

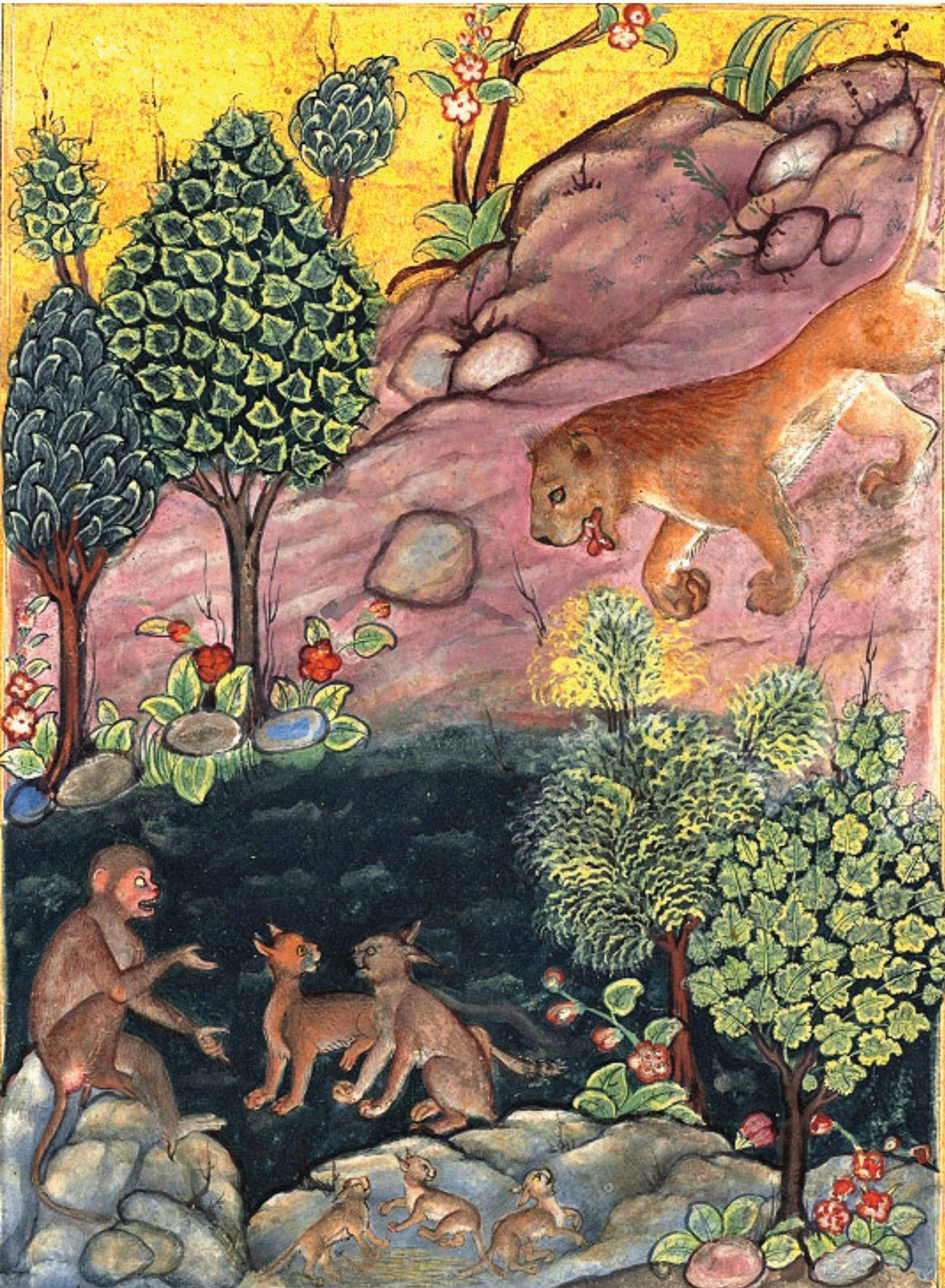

Third of four illustrations from a manuscript of the Tutinama commissioned during the reign of the Emperor Akbar. Credit: The Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. A Dean Parry 1962.279.193.a.

The lion once more approached his home, and the female syagoash again made her cubs cry. The syagoash called out to the female, Do you quiet the young ones; to-day I shall find lion’s flesh, because the monkey, who is my friend, has bound himself by an oath to deceive the lion and bring him hither this day; do you wait a little, and silence the cubs – suffer them not to make a noise; if he should discover my voice, he will not come here. When the lion heard these words, he immediately seized the monkey, and having torn him in pieces, took to flight, and never returned to the place again.”

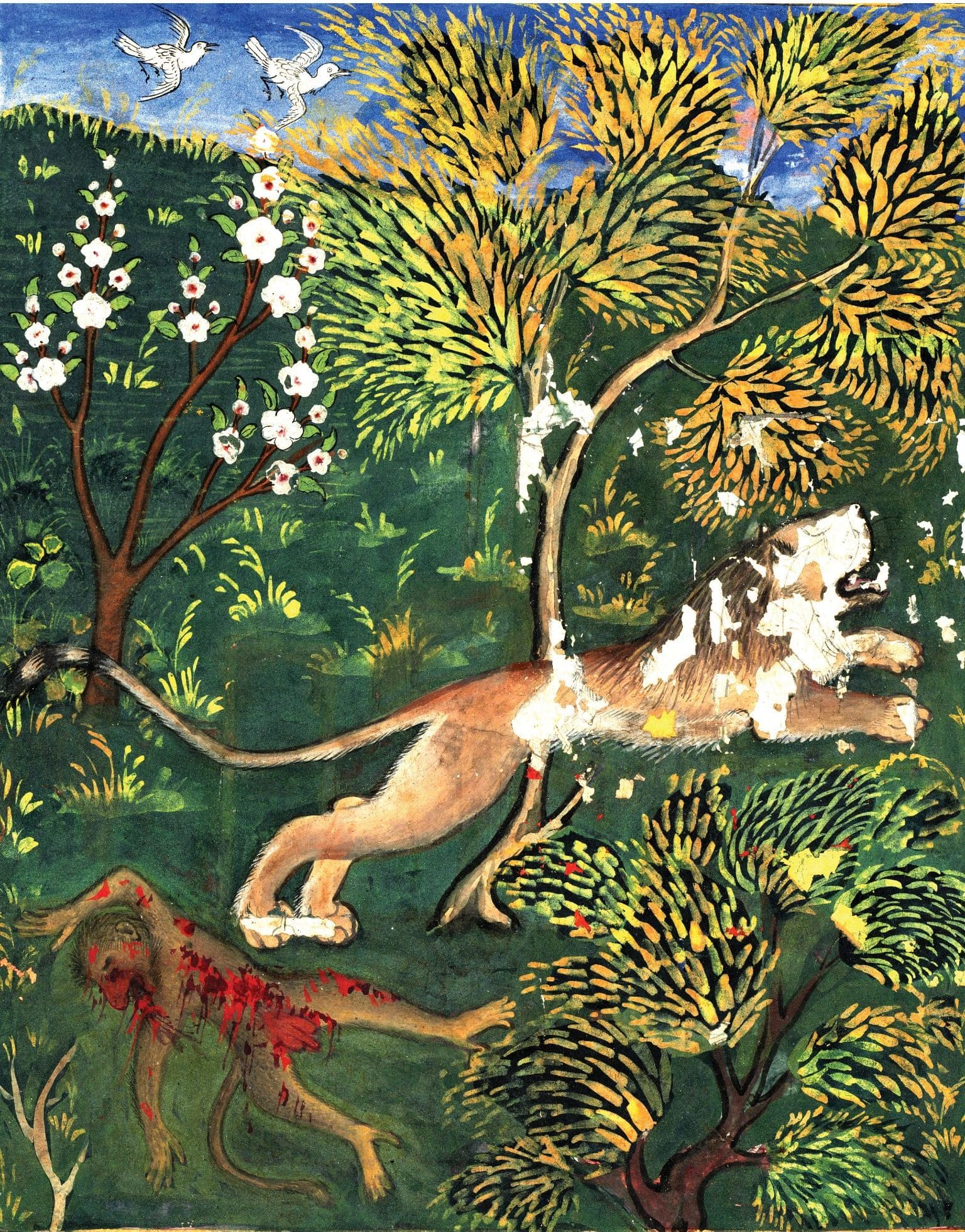

Fourth of four illustrations from a manuscript of the Tutinama commissioned during the reign of the Emperor Akbar. Credit: The Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. A Dean Parry 1962.279.193.a.

The parrot, having concluded the tale of the syagoash, said to Khojisteh, “Arise and go to your lover.” Khojisteh wanted to have gone; at the very time the morning birds made a noise, and the day appearing, her departure was put off

(Anonymous, 1801)

This excerpt from Caracal: An Intimate History of a Mysterious Cat by Dharmendra Khandal and Ishan Dhar has been published with permission from Tiger Watch.

This excerpt from Caracal: An Intimate History of a Mysterious Cat by Dharmendra Khandal and Ishan Dhar has been published with permission from Tiger Watch.