A race of only 192.28 meters in length. That humble, that simple, that brief was the beginning of the Olympic Games. A modest test with a humble winner: a chef from the Elis region called Coroebo (or Koroibos or Choroebus, according to different translations). In the year 776 BC, he ran faster than any other competitor the distance of ‘one stadium’ and returned to his city crowned with olive twigs. Was the chef the first champion of the first Olympiad? Many historians asseverated that Coroebo was not the inaugural winner, but his name was the first to be engraved in stone at the head of a long series of heroes, also mentioned in poems of Homer or Pindar.

The foot race was part of a variety of religious and cultural rites that took place every four years, over six days, in a plain located next to the sanctuary of the city of Olympia, famous for its temple dedicated to Zeus, one of the seven wonders of the antiquity. It is estimated that the pedestrian test would have begun to be disputed at least 150 years before Coroebo, although this is only a conjecture.

Beyond its origin, after the victory of the chef, the games were consolidated and, through their successive editions, they grew in number of participants, who came first from all corners of the Hellenic world and later, from the different provinces of the Roman Empire. Likewise, other tests were added to the simple 192.28-meter contest: a two-stadium race (called diaulium, 385 meters), four stadiums (769 meters), eight stadiums (1.538 meters) and up to twenty-four stadiums (known as Doric, 4.614 meters). Then, the pentathlon appeared (a competition that combined five disciplines: race, discus throwing, javelin throwing, long jump and fight), hoplitodromia (race wearing armor and carrying spear and shield), pugilism and horse-quadrigas. Boxing began with no difference of categories by weight or protection of any kind. The duels had no assault limit and ended by knockout or abandonment of one of the fighters. Over the years, leather strips were incorporated to protect the hands and make the blows stronger. Some boxers added small stones, lead fragments or wood chips to the straps to cause more damage to their rivals. The fights generated so much passion among the public that a new type of contest was added, designed especially for those who enjoyed the blood: the pancracy, an ‘everything’s fair’ kind of carnival, that included bites, asphyxiation, kicks in the testicles and even sinking the fingers in the eyes of the rival. This new addition extended the Olympic calendar to seven days.

Also Read: Can the Tokyo Olympics help bring the world together?

Since its inception, the games were conceived as a period of spiritual and religious recollection. Shortly after, they were dressed with a nationalist halo. In the 9th century BC, the kings Ifitos of Élide, Cleóstenes of Pisa and Licurgo of Esparta instituted what is known as the ‘Olympic truce’, an initiative that suspended all kinds of war actions between the Greek city states during the week of the games. They also established a ban on entering Olimpia, ‘a sacred place’, armed,—‘Who dares to penetrate it with weapons will be considered sacrilegious’.

But not everyone could particpate in the competition. In the early days, only the Greek males were considered as ‘free men’—legitimate sons with full possession of all civil rights, who had not committed anything sacrilegous ever. Then, for political reasons, contestants from other nations were accepted, in some cases by imposition, as happened with the Roman emperor Nero. The rules and codes of competence were engraved on bronze tables located in one of the temples of Olympia. The contestants had to arrive in the city at least four weeks before the beginning of the competition, to establish themselves in a kind of ‘campground’ where training was alternated with the study of competition rules, and where everyone had to take an oath that guarranted respect for the decisions of the judges and ‘loyalty for the competition’. In the 5th century BC, during the final of the boxing tournament, a participant named Cleómedes killed his opponent. The judges disqualified him because they suspected in him some sort of a malice and a sense of trechery to the spirit of the game, and named champion ‘post mortem’ to his rival.

The winners only received a crown made with leaves and twigs of olive as a prize. However, their exploits gained importance to such an extent among their countrymen from the different city states, that they enjoyed benefits not far from that of the current government celebrities—tax exemptions, life pensions, houses, food and other goods allowed the heroes to enjoy a life relaxed and luxurious.

Also Read: Can’t cancel, can’t hold – Tokyo Olympics was going to help Brand Japan, now it’s a headache

What was the role of women in the Games? Priamarily, there were no competitions reserved for them in the Olympic calendar. They only performed in some kind of a manifestation that juxtaposed sport and art in honour of the goddess Hera, which was held at another time of the year. Only single women and girls were allowed to attend Olympia as spectators. Married women were prohibited from witnessing the different sports, under the penalty of death. The only known case of violation of these rules corresponded to Callipatria, a woman who disguised herself as a man to see her son Pisidoro in the boxing competition. When the young man prevailed in the last fight, Callipatria forgot about the harsh rules, and overwhelmed by emotion, pounced on Pisidoro to hug him, not noticing that the linen cloth covering her face and hair dropped. The judges and spectators discovered the deception, but the woman was forgiven for being a daughter, sister and mother of Olympic champions.

The Olympics of antiquity ran until 394 BC, when they were abolished by the Roman emperor Theodosius I at the request of the Milan bishop, Aurelius Ambrosius (later St. Ambrosius), who considered them immoral and promoters of atheism. The decree not only prohibited the Games but also established the death penalty for those who tried to reissue them. Half a century later, another monarch, Theodosius II, ordered the destruction of all the temples of Olympia. To this brutal Roman disposition was added a series of earthquakes that ended up burying the remains, which remained hidden for twelve centuries. In the mid-19th century, a group of European archaeologists discovered the old ruins and the light illuminated the Olympic glory again. A few decades later, a French nobleman, Pierre de Frédy, Baron de Coubertin, came up with the crazy idea of returning life and greatness to the majestic Olympic Games. Well, not so crazy. The Theodosians were no longer there to enforce their absurd orders.

Also Read: No cheering, singing, whistling — All that is different as Tokyo gets ready for Olympics

Nero, the champion

Many monarchs and emperors of ancient times decided to participate in the Games to demonstrate their aptitudes in sport. Philip II, king of Macedonia and father of Alexander the Great, won horse and chariot races in 356 BC. Another contestant was the Roman Nero. The history books and the movie Quo Vadis expose the emperor as a vain and murderous psychopath. In spite of ordering bloodthirsty campaigns, liquidating his rivals and even his mother, a brother and his first two wives (the second, Popea, was killed by Nero by a savage kick in the stomach that caused abortion and death due to bleeding), the despot supported the development of the arts and ordered the construction of numerous theatres and schools. Nero believed himself a descendant of Apollo and owner of an unmatched talent for music and poetry. However, the only ones who applauded and cheered their works, and interpretations were the members of a ridiculous claque that earned generous salaries to flatter the monarch’s ears. In 67 BC, the emperor became obsessed with the Olympic Games and set out to win an olive crown. At any cost. The tyrant enrolled in the chariot race and bribed his rivals so that, as the competition spread, they were dropping out. Nero finished the race by running alone and won despite having fallen awkwardly in a curve. The Greeks looked to the sky to question their gods. Little would have cost them to break the dictator’s neck.

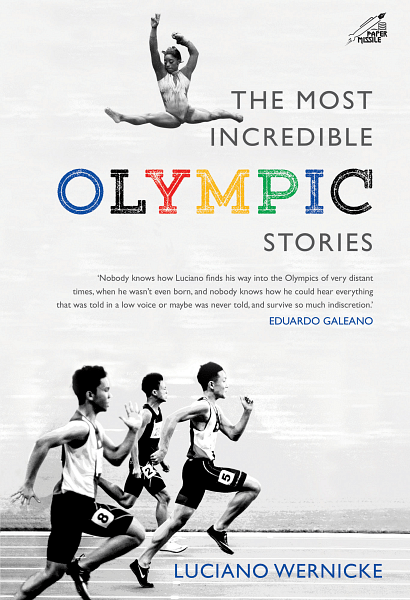

This excerpt from ‘The Most Incredible Olympic Stories’ by Luciano Wernicke has been published with permission from Niyogi Books.

This excerpt from ‘The Most Incredible Olympic Stories’ by Luciano Wernicke has been published with permission from Niyogi Books.