As an Indian widow, Kamala could have chosen “to immerse herself in negative mourning for the rest of her life,” according to custom; as an English-educated reformist, she might have been a political activist in the public realm. Instead, she chose the middle way “of economic independence and creating a happy home” for herself, her family, and her community. Although her “love of silence, her serenity and independence were her main characteristics …. [h]ers was a positive dynamic personality. Neither did she believe in self-effacement or … martyrdom,” as was expected of Indian widows.

As a Christian, Kamala was not held to the same standards as Hindu widows, and yet she chose to proclaim her widowed state by wearing “only white, grey and dark red saris for many years”; she loved fresh flowers but “could not bring herself to wear . . . [them] in her hair,” according to Indian ladies’ signature style. (Lakshmi np) Given that the customs and attitudes dictating widows’ lives were so deeply entrenched, her independence and professionalism are unusual and exemplary. If Satthianadhan was not a cuttingedge figure in the popular sense, her example represents purposeful contributions to women’s and nationalists’ endeavors nonetheless.

Kamala’s signature credentials reflect the eclectic intellectual fabric of fin desiècle Madras. The venerable Satthianadhan family was well-respected and highlyregarded as Indian-Christian educators and social workers, yielding several links with British royalty. Kamala’s parents-in-law, Anna and W.T. Satthianadhan, because of their missionary and education work in south India, were presented to Queen Victoria in 1878. A generation later, Kamala participated in Lady Ampthill’s Purdah Party welcoming Mary, Princess of Wales (later Queen) to India. (Portrait 35–36)

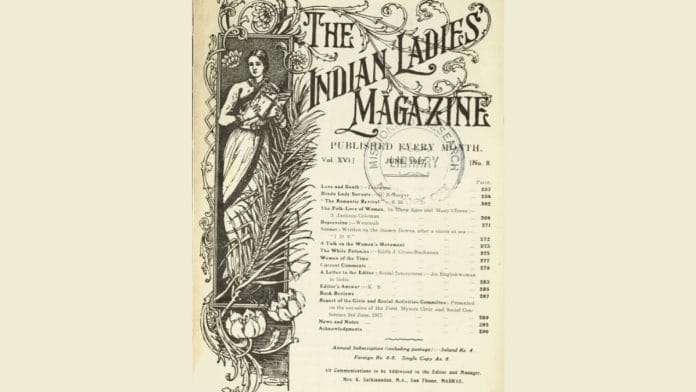

Kamala served as translator to the Princess, for which she was given a signed portrait, featured as the frontispiece for ILM’s coronation number in 1911. In 1941, Kamala was honored for her contributions to education and the promotion of women’s issues with an MBE (Order of the British Empire) and a Coronation Medal. Well-educated and articulate, traditional yet liberal-minded, she was positioned between East and West, ancient custom and modern innovation, Christian humanism and Hindu cultural authority, British imperialism and Indian nationalism; not uncritically, she embodied all those influences together, and it was this synthesis that shaped ILM’s inclusive editorial platform.

Distinct from the short-lived movements of “extremists” and public activists, Kamala maintained that “[a]dvance cannot be from the circumference to the centre, but from the centre outwards; and then only will it last.” (ILM “Ourselves” 1930: 274) For her, this philosophy was deeply personal: a widowed, single mother, she was committed to “retaining all the chaste modest traditions” of Indian womanhood while promoting a modernizing spirit of autonomy and selfsufficiency. (Sengupta, Portrait xii)

Distinct from the highly public profile of her friend, nationalist-activist Sarojini Naidu, Kamala preferred “serving her country” from the platforms of home, family, and community (3); other newly-liberated women took to the streets as protesters, to podiums as lecturers, to conferences as policy-makers, and to jails as political prisoners. Preferring to cultivate social solidarity and avoid divisiveness, Kamala incorporated conservative views about women along with more progressive insights; in this, she aligns with such activists as girls’ education advocate Rokeya Hossain (who denounced purdah but wore a burkah in public) and Dr. Rukhmabai (who refused an arranged marriage but adapted widow’s garb when her rejected spouse died). For all women reformers, striking a balance between traditional values and modernization, and between conservative, liberal, and radical activism, was a perpetual concern.

As nationalist separatism intensified prior to independence, Satthianadhan was among those conflicted by the expectation that she choose between Raj and swaraj. She was notably proud of having been the first to publish many of Sarojini Naidu’s poems, repeatedly according “our Indian poetess” pride of place in ILM, complete with elaborately designed graphic presentations: “The contributions of no lady writer to our columns are so well appreciated by our readers as the beautiful verses from … [her] pen.” (ILM “Sarojini” 1902: 250) That the militant and influential Naidu later dissociated herself from the struggling ILM was a painful betrayal to Satthianadhan; aptly symbolizing their radically divergent paths, Naidu was imprisoned for her political activism (1932 and 1942), while Satthianadhan was twice honored by the British government for her social work.

Kamala saw Indian women as “‘handicapped in every way by evil degrading customs.’ Child marriage, the purdah, lack of education and restrictions on widows crippled the country. Hindu women themselves were loath to change these customs, because they thought it their Dharma or duty to practice them.” (Sengupta, Portrait 48) ILM confronted these entrenched customs with tact, sensitivity, and concern for the individual, familial, and communal costs involved both in perpetuating them and in thwarting modernization, nationalism, and independence.

For Kamala, the amelioration promised by companionate marriage must begin early, in childhood, through facilitating “the healthy companionship and mixing of boys and girls, thus breaking the barriers between men and women, which has been the root-cause of so much orthodox unhappiness in India.” (Sengupta, Pioneer 123) As many selections in this volume attest, extreme gender separatism, and the practices and beliefs underpinning it, accounts for an array of obstacles thwarting the progress of India’s rising generations.

Statesman Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan praised Kamala for her contributions to “the emancipation of women, which is the most significant feature of our time.” (Sengupta, Portrait ix)22 This point is central to understanding her often contradictory negotiation of woman’s place—in private and public realms, in terms of oppression and liberation, and as the pre-requisite to India’s identity politics, modernization, and independence.

For example, outlining “Different Pictures of Women” in the midst of women’s suffrage debates and World War I, she essentializes womanhood by comparing the “manly woman” or “manlike women” to the womanly-woman, who is gentle and reticent, like a “hedgesparrow … the very opposite of … man. If women should ever grow to be like men, then reverence would be at an end, ideality would vanish, romance would perish.” (ILM “Different” 1916: 20) But in the same article, she praises the “man-woman suffragette[s] … the war-woman—the women engine cleaners, the women farmers, the women road-sweepers” who have kept the economy and society functioning while men are away at war: “women of the present day are showing themselves capable of better things … All honour to them,” particularly “the heroism of the nurses.” In this new world order, there is no room for the fastidious lady, “whose fineness flourished in proportion to her uselessness.”

But just a year later, Kamala objects to “Indian women competing with men in all the departments of public life. We are old fashioned and maintain that woman’s proper sphere is the home, and in that sacred retirement, her activities should be unceasing.” (ILM “Indian” 1917: 166) Indian women are superior to “superfluous” European single women, who take “advantage of the war to compete with men” (167); but she contradicts herself again in that same article, asserting “[i]t is only a matter of time. Indian girl graduates must persevere and break down this last barrier to women’s activities.” Such mixed editorial messages indicate an urge to placate competing perspectives, with a view toward facilitating harmony rather than stoking controversy or alienation. This characteristic marks ILM’s contributions to Indian women’s periodicals history as both progressive and essentialist, an ambiguity that likely contributed to its demise.

The influence of English language and literature on India’s literary history raises important points regarding its emergence as a modern nation. British Victorians valorized the Angel-in-the-House, a concept that reifies gendered divisions of labor and the accompanying personal and professional, economic and political strictures binding women’s lives. The good woman was one who stayed at home, engaged in domestic pursuits; she had no need for life outside her home, away from family and domestic chores. In India, the concept was far from alien: there, a good woman spent her existence in purdah, in isolation from the outside world. Insofar as sexual respectability is the primary concern, there is no need for education, literacy, accomplishments, or self-development. Britain’s Angel-in-the-House was a welcome concept to those nationalists purporting to adapt western innovations—so long as they align with pre-existing socio-cultural practices and attitudes.

ILM’s editorial principles reveal a timely synthesis of Angel-in-theHouse domestic ideology and New Woman rights and responsibilities with the “awakening” of Indian women to the modernizing, nationalist, and independence movements. While Satthianadhan baulked at radical female militancy, whether English suffragists or Indian freedom fighters,25 Victorian gender ideology offered a suggestive model for reforming the status of Indian womanhood in ways that would preserve and protect—rather than compromise, as was popularly feared—its defining qualities. Once passed through a “nationalist sieve … selectively adopted … [and] reconstituted,” (Chatterjee, Lineages 86) the resulting “awakening” found expression in writing that eloquently records India’s spirit-of-the-age.

The Life Literary is a collection of Indian women’s original writing, offering keen insights into “the possibilities of using literature as historical source material… an entry-point into the many mental worlds of the reading and writing communities.” (Ghosh 296)26 Much critical commentary about Indian women’s writing in English relies on faulting authors for being imitative, unoriginal, and derivative or, alternatively, defending them against those very charges. This study emphasizes what they did accomplish, rather than where they were thought to have failed. While some ILM entries do exhibit what might constitute linguistic or literary mimicry, Satthianadhan privileged the message over the medium, valuing content over style. ILM being a welcoming, non-judgmental resource, the fact of the articulation is itself the primary point.

As an English language publication, ILM addressed English, Anglo-Indian, and Indian editorial considerations; ideologically, its dominant framework stressed the essentialist idea that woman’s place is in the home—the most basic commonplace linking East and West. Thus, its editorial platform is both predicated on and anxious about a gender ideology that was increasingly out of step with the time; that its critical values incorporated East and West, ancient and modern, Angel-in-the-House and New Woman resulted in an ambivalent gender ideology uncertainly poised between the known drawbacks of traditionalism and the unknown risks of modernism. As an avenue for women’s social activism, ILM proves to be exceptionally innovative—at once a product of its time, ahead of its time and—dramatizing the speed with which Indian women internalized western modernization to defeat imperialism—by the late 1930s, slipping into redundancy.

ILM offered a unique platform for Indian women writers, many of whom have disappeared from historical records that foreground the Gandhi / Nehru / Jinnah nexus as if that alone accomplished independence. The Life Literary provides abundant evidence to the contrary: evidence of the less visible contributions of the “other” half of the population, the Indian women who for decades established and developed the foundations of India’s nation-building— and then wrote about it. These are their contributions to India’s “national autobiography.”

This excerpt by Deborah Anna Logan’s ‘The Life Literary’ has been published with permission from Jadavpur University Press.