Just as the Urdu language used in Lucknow became increasingly refined, so did the sentiments conjured by the language. Emotion itself was shorn of all things sordid, and developed what would become the calling card of Lucknawi expression—its delicacy or nazakat. Verse upon verse would describe the sublime agony of separation, or unrequited love, using imagery subtle as shadows and language as delicate as a lover’s sigh. A popular adage of the fastidious lengths to which Lucknawi delicatesse could extend to was Lakhnau ki nazakat hai ki rasgulle bhi chhil ke khaye jate hain. And the poetic genre par excellence to capture this mood became the Urdu ghazal. In time this delicacy of sentiment would be deemed excessive and wanton, its

proponents similarly derided as effeminate and decadent. But in the late eighteenth century, these evenings of exquisite music and dance in Lucknow would become so famous that a saying was created: Subh-e Benaras, Shaam-e Awadhwa, Shab-e Malwa.†

And yet the first wave of poets who migrated from Delhi to Lucknow would not be entirely complimentary about their adopted city. Indeed, they were sometimes bitter in their vitriol, and scathing about the brash new city they had moved to, especially when compared to the remembered grandeur and elegant decrepitude of the grand old Mughal city of Delhi. ‘Far better than Lucknow the ruins of Delhi,’ mourned Mir Taqi Mir, the finest ghazal writer of his time, with unvarnished scorn. ‘Would that I had died back there / than let my madness lead me here!’ Mir would live the rest of life in Lucknow, and would make an art form of his prickly truculence regarding Lucknow and its citizens, and would go out of his way to belittle everyone around him. When the Lucknow cognoscenti asked Mir to recite his poetry for them, the scornful poet demurred, saying that it would be quite beyond their understanding for ‘to get my poetry you need to understand the language that is spoken at the steps of Delhi’s Jama Masjid,‡ you do not.’ Mir struggled to reconcile himself to a changing order, one in which his unfashionably sober clothes were gently mocked, and the brash and brassy confidence of the Lucknow elite was an grievous insult. The best known story about his introduction to this sparkling new world was when he entered a mushaira for the first time, his frayed dignity wrapped tightly around himself, and no one recognized him for the great poet from Delhi that he was. When it was his time to recite a poem, these are the verses he pronounced:

Why do you mock at me and ask yourselves

Where in the world I come from, easterners?

There was a city, famed throughout the world,

Where dwelt the chosen spirits of the age;

Delhi its name, fairest among the fair.

Fate looted it and laid it desolate,

And to that ravaged city I belong.

Mir was around sixteen years old when his beloved city was devastated by Nadir Shah, and he would never recover from the horror of that desecration, and the nostalgia for all that he had lost:

This age is not like that which went before it.

The times have changed, the earth and sky have changed.

On one occasion, when Asaf failed to pay sufficiently respectful attention to Mir while he recited a ghazal, distracted by the fish in his pond, the poet was quick to show his displeasure. But the nawab cheerily refused to be insulted, and continued to pay the poet his stipend till the end of his life. The nawab could console himself with the knowledge that Mir had insulted the emperor himself, when he was in Delhi. The emperor had once rather impetuously claimed that he himself was such a good poet that he could churn out verses while performing his ablutions in the morning. ‘Yes, and they smell like it,’ was Mir’s stingingly predictable rejoinder. In Lucknow, Mir’s ‘deeply emotional and sincere verse’, wrote a scholar, ‘appeared old-fashioned in Asaf-ud-Daula’s court, yet his mere presence brought fame to it.’

Another great Delhi poet who made Lucknow his home was Mirza Muhammad Rafi ‘Sauda’. Sauda was given an annual grant of 6,000 courtesans and poets 255 rupees by Asaf and he lived in the city, with rather less angst than Mir, till his death in 1781. Nevertheless he too delighted in satirizing the nawab and when he heard that Asaf had killed a lion during a hunt, composed the following couplet:

See, Ibn-i-Muljam comes to earth again

And so the Lion of God once more is slain

When he learnt of these lines the nawab was understandably startled. The ‘Lion of God’ was one of the titles of Imam Ali himself and Ibn-i-Muljam the name of the man who had killed him. ‘Mirza, I hear you have compared me to the murderer of the Lion of God?’ he asked the irreverent poet who answered laughingly, ‘well it was a fair comparison. The lion was God’s, not yours or mine.’

Perhaps even more galling for Asaf would have been the lines of the other great Delhi émigré poet, Mir Hasan. For Mir Hasan revolted against the physical fact of the city of Lucknow itself:

When I arrived in the land of Lucknow

I saw no pleasure in that town.

Grief had so besieged my soul,

I felt I could never take to this place,

Even if there are many pious people here,

What shall we do if the place itself is bad?

One of the features of Lucknow that caused such turmoil in Mir Hasan’s sensitive Delhi poet’s soul was its undulating nature, with its gentle rises and dips. ‘This country is settled on bumpy ground, so that its paths wind all up and down.’ He huffed about the narrow alleys: ‘Each lane is so narrow here, that it’s scarcely possible to take a breath.’

As for another great émigré poet, Mushafi, the critique appeared personal to the point of insult:

Lord, you’ve robbed me of my city

Brought and sat me in this wilderness

What can there be between me and these Lakhnavis?

Dear God, what have you done to me?

So even while the artists in their paint-splattered ateliers were producing the perfectly ordered and paradisiacal stepped terraces and courtyards typical of this age, the poets were hinting at a more disorderly reality. From the sheer quantity of construction activity begun by Asaf at this time, it is certain that there would have been heaps of rubble and debris, as well as the elegant terrace buildings that would be immortalized in paintings and later poetry. Nonetheless, perhaps with an abashed eye upon the source of his patronage, Mir Hasan* himself admitted piously that Asaf had much to be praised about:

May Asaf-ud-Daula be kept safe forever

For he made the plans for his stay in this place

He put an end to all the dirtiness here

And gave a real shape to Lucknow.

It must have been a great trial upon the nawab’s patience to withstand the many barbs of these Delhi poets. And yet when one of the Mughal princes also used poetry to deliver a veiled castigation, the nawab reacted with his usual good humour and charm. On one occasion during the Holi celebrations, Azfari felt that his royal cousins had not been treated by Asaf with quite the deference they were owed, and this prickly Mughal scion extemporized a few verses to this effect. On hearing this poetic complaint, Asaf smiled and promised to assure the cousins a proper stipend too, a promise which he held till the end of his life.

Perhaps Mir’s most devastating critique would be of Lucknawi poet Jurat’s ghazals which he called ‘not poetry, but descriptions of kissing and licking’ (chumachati). This particularly colourful insult is believed to have been caused by Jurat’s use of a notorious Lucknawi innovation—Rekhti. If the lofty Urdu ghazal used the normative masculine Rekhta voice, then Rekhti arose as the self-consciously playful and feminine anti-ghazal. Instead of the cerebral themes of ghazals, Rekhti provocatively presented the quotidian and the feminine, while adopting the voice of a woman: ‘the travails of burdensome husbands; the annoyances and quotidian spats between housewives and their domestic servants; the rivalries among co-wives; and the lascivious shenanigans of illicit liaisons—including within the zenana itself ’. The idiom of Rekhti is sometimes called ‘begamati’ zubaan’ (language of the respectable women) though, paradoxically, poet Rangeen, who is credited with inventing Rekhti, claimed to have acquired an understanding of the idiom during an ill-spent youth in the company of tawaifs. Rangeen adopted a woman’s name, Anvari, dressed up in women’s clothes and exhibited feminine mannerisms when he recited his poetry. Rekhti had much in common with the Bhakti mode of song and poetry in which the poets identified as women and sometimes dressed up as women while singing to their beloved Krishna. In time, this aspect of Lucknawi poetry would also be used by the British to question the nawabs’ masculinity.

Despite the unshakeable nostalgia for Delhi, however, almost all of the great Delhi poets flocked to Lucknow. It was said that there were more Urdu poets in Lucknow than lived in the rest of India. And since the grandeur of a court in India was gauged by the excellence of its poets, Asaf brought blinding brilliance to his own court while simultaneously dimming the lustre of the Mughal court.

Mir ‘Soz’, a Delhi poet outstanding for his ghazals, was appointed ustad, or poetry teacher, to the nawab. Not only was the nawab a poet himself, but ‘at least one of his wives, most of his successors, and many of his prominent courtiers and officials were poets in their own right, some of recognized quality even today’. Asaf was considered a passably competent poet, Mir himself writing graciously about the nawab’s poetry. One of Asaf ’s verses was as follows:

Oh Asaf, the story of this life is so delicate,

That it ends in a jiffy.

In time the great Delhi poets would die out, their place taken by a confident new generation of Lucknawi born and bred poets, the most famous of whom would be Shaykh Imam Baksh ‘Nasikh’ and Khwaja Haider Ali ‘Aatish’.

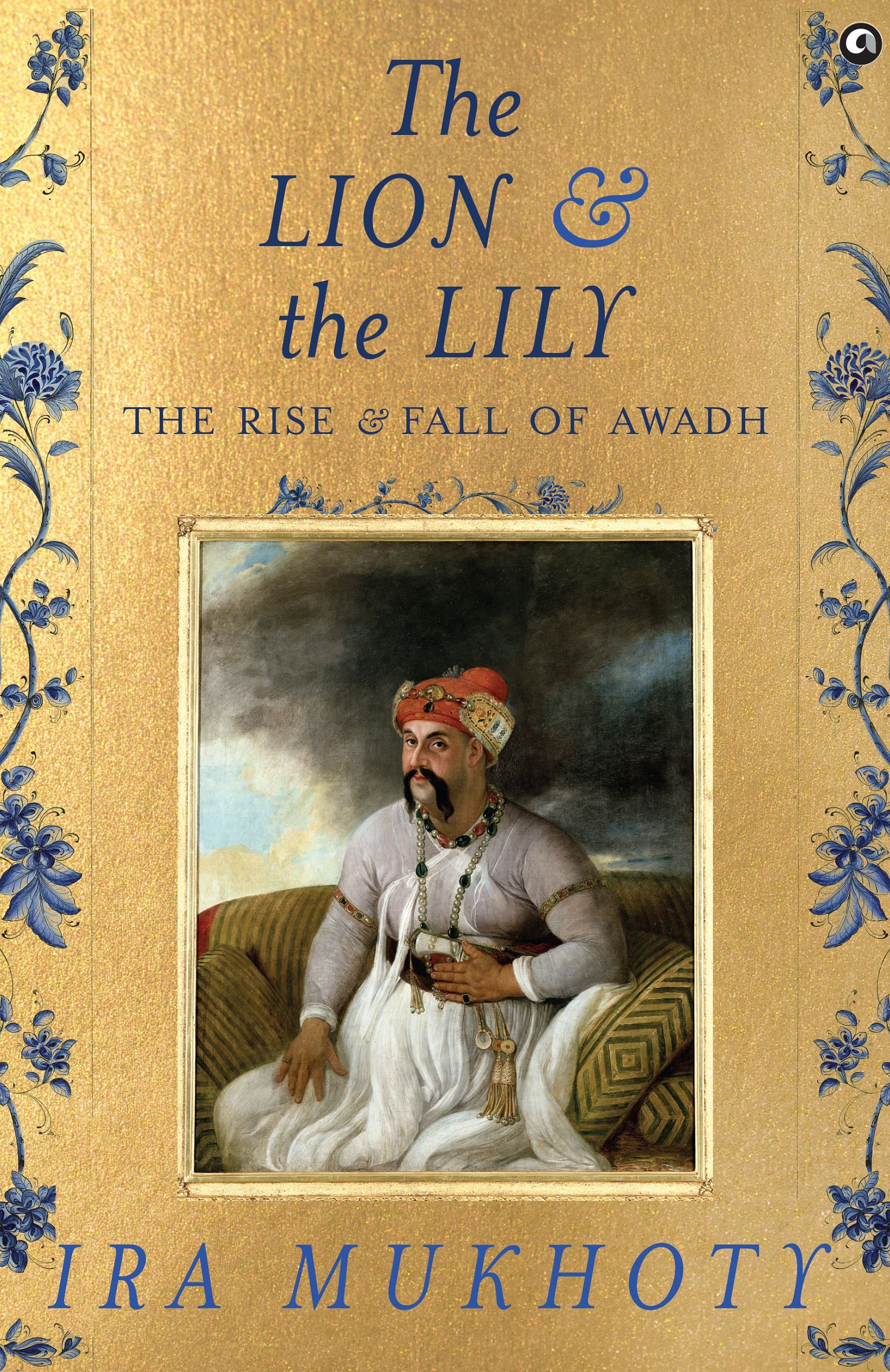

This excerpt from The Lion and The Lily: The Rise & Fall Of Awadh has been published with permission from The Aleph Book Company.

This excerpt from The Lion and The Lily: The Rise & Fall Of Awadh has been published with permission from The Aleph Book Company.