The book is British-Indian journalist Mark Tully’s second run-in with fiction, and the stories are all tied to Rajiv Gandhi’s India – the late 1980s.

When Mark Tully speaks of India in his writing, it is hard not to have two creeping doubts—will he be culturally insensitive, or has he gone native, so to speak?

However, his work over the years – several books of non-fiction and a collection of short stories – controverts both doubts, considering how close he has always been to his beloved subject matter. The Padma Bhushan and the Knighthood he received are testaments to his journalistic sensitivity, which never interferes with the writer’s detachment he shows towards the object at hand.

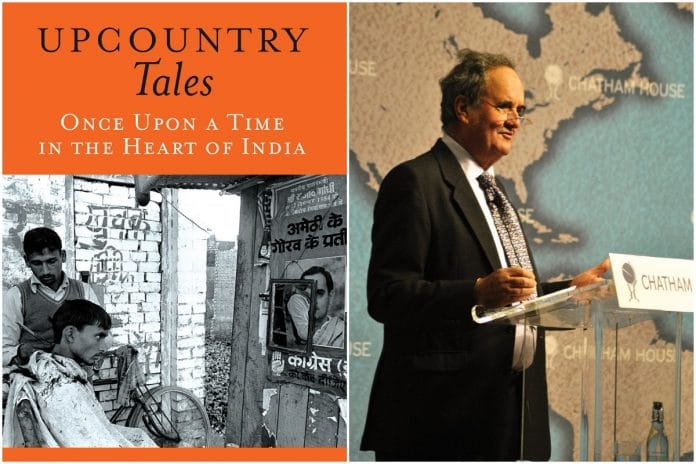

Writing at 82, ‘Upcountry Tales: Once Upon a Time in the Heart of India’ is his second run-in with fiction. It shows, more than anything else, that the recollections of his penetrating insight into the Indian polity can be read in many ways. The stories themselves are tightly tied to what Tully calls a “dead end” in Indian history, especially focusing on the latter half of the 1980s, and what he has to say about the country under Rajiv Gandhi’s rule.

I think Beckett had the right approach here. If an author is too preoccupied with the idea behind the piece of fiction being written, then it would be better to write an essay, as opposed to fiction. Tully’s seven short stories, in one way or the other, try to become illustrations of Rajiv Gandhi’s rickety India, bouncing unsurely towards uncertain transformation.

In doing so, they remain neither compelling short stories, nor the slice-of-life semi-fictional pieces about life in eastern UP, which Tully might have had in mind. They do pose an interesting question though: How important is it for fiction based on socio-political realities to be slightly fantastical at the cost of reality?

The second story in the collection, “Murder in Milanpur”, is a good example to get started on. Thakur Ranvir Singh is discovered dead in his bedroom in Milanpur, an otherwise sleepy little place, whose landlord had never quite accepted the end of the Thakur Raj. In the thick of it, is thanedar Prem Lal, a model and honest cop, who ended up as a policeman instead of a teacher, because his father insisted that the police “get plenty of opportunities to earn a lot of money”.

From then on, it is a saga of false accusations and a search for the truth, with Prem Lal fighting not just against crime and injustice but also the complacency of two CID officers who want to quickly put someone behind bars and rush back from the backwater to the Centre.

The story attempts to valourise the peripheral over the centre. Repeatedly insisting on the CID officers’ lack of knowledge about the “grassroots”, it pokes at an establishment far removed from the hinterland, yet making policies for an India it did not understand too well.

Other stories also scrape at these varied centres of power, dealing with a kerfuffle between Dalits and Brahmins, or with the apprehensive ploughman Tirathpal, stuck between tractors and bullocks, or with the clueless foreign-returned son of a dead local politician. They all poke and scrape, however, without piercing through.

Tully seems to not want to belie the sense of optimism, coursing through the land where his great-great grandfather was an opium agent and his great-grandfather, a trader. But the lack of an edge to this critical history of India might just be because Tully, as he once confessed in an interview, was “soft on Rajiv Gandhi when he came to power”.

Upcountry Tales is firmly rooted in the historical conditions which are explained at length, in almost all of the stories, but the rhetoric misses the backbone of Tully’s earlier writing, such as “Ram Chander’s Story” in the 1991 non-fiction collection, No Full Stops in India.

There is another answer to the balance between reality and fiction that Tully offers, specifically in the story “Slow Train to Santnagar”. It stands out because it is self-aware of the weird, magical art of telling stories which are hard to believe – like gossip filtered and memory readjusted through generations of lore. A bus races a train in an edge-of-the-seat fight against a corrupt politician, an oblivious government, and old steam engine pipes. Tully retells B.R. Chopra’s Naya Daur for the 1980s, writing with an acute awareness of pace and the thrill of cinematic flair.

In this story, as in several others, the stock trope is that the media saves the day by pressuring the establishment into accountability, but it works in this story better than the others, because it is used as a device with a purpose, along with other tropes, like the MP who wants money and the traditionalist who wants to stick to steam engines in the age of diesel.

Tully’s storytelling comes closer to the oddness of life which might be real, but is certainly beyond the believable. The prose loses the need to give accounts and dives into the uncanniness of telling tales, and for once the “once upon a time” of Tully’s writing moves away from “historical stories” about India in the 1980s.

Shantam Goyal is a writing tutor at Ashoka University, while also doing his M.Phil from the Department of English, University of Delhi.