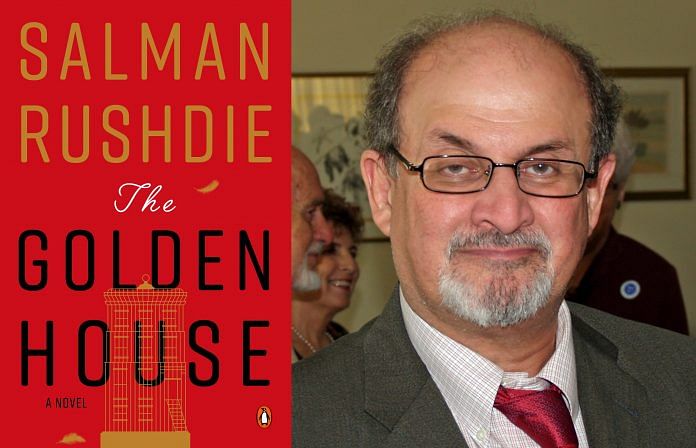

Stacked like a neat game of Tetris, ‘The Golden House’ sticks true to Salman Rushdie’s whimsical style of writing.

It would be terribly repetitive to say that Salman Rushdie’s new novel, The Golden House, is stacked like a neat game of Tetris with references which die out and disappear once their purpose is served. It would also not work to say that the bulging bag of video games, films, novels, mythology, history, tropes of video and language, and geographies and social justice is close to coming apart and scattering all over at the touch of a nail. What can instead be noted is that the greatest of his references, the one in which his plot unsteadily swims, is the one which remains unmentioned throughout: The Golden House is a twisted, upside-down retelling of Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov.

There is the father, “the man who called himself Nero Golden,” and his three sons who are an admixture of known and lost bloodlines. They too are allowed to call themselves what they want to even as they are pulled by their father into the exile of being a Golden and being in New York. What they have left behind is more than just the city of Bombay – they have walked away from the terror of 26/11 and the gangland intrigue of its streets into a life marred with death by exile.

And in true Dostoevskian reverb, they are all culpable for these deaths, or rather, everyone is guilty. The novel’s murders are carried out by guns which have a life of their own and by the past which, unlike Rushdie’s references, does not eventually die out into non-existence. Instead, the past becomes the “city that could not be named” in the “country that could not be named” where mistakes were made which could not be unmade. America kills and India also kills.

Multiple Voices

The thousands of voices in Rushdie’s dialogue make active, breathing beings out of New York and Bombay. These voices are panicky, drowning in crises of gender-identity, and of the tarnished fight for presidency between Batwoman and the Joker with his Suicide Squad screeching in “the segment of the country that was as crazy as he.” It is impossible to not see something of Trump in Nero Golden himself.

With his fingers dipped into all corners of new real estate, limitless resources, and his Russian partner who is slowly swindling the life-blood out of him, Nero seems almost harmlessly gullible, yet all the more dangerous because of his self-assured illusion of control. There is a lot happening, and this has never been a problem for Rushdie before. His earlier fiction is deft at funnelling every brilliant little glint of thought into that one moment where we hold our breaths for every being on the page suspended with their breaths held, waiting for the one implosion which would crumble all meaning into the one bare concern of the novel.

The good and the evil

The bare concern of this novel is good and evil. This is what René, the Ishmael of The Golden House, the storyteller and filmmaker who is making a movie out of the lives in the Golden House, would have us believe. In every chapter he etches out scenes, ending sections with a definitive “Cut” and “Flashback” and “Blackout” to frame with great clarity his documentary, mockumentary, or perhaps feature film. The problem with the story he is telling us is that it does not crumble into bare good and evil. It hardly even muses upon the impossibility of bare good and evil. Instead, when the smoke clears, we find that the stack of Rushdie’s rich detail has overshot its mark and the game of Tetris has been lost somewhere beyond the screen. Game Over.

What we are left with is a novel which is funny, which moves across maps and systems of knowledge, schools of thought, and a wealth of stories behind characters we will not care much for. We are also left with a long watchlist of global cinema – we may call it “René Recommends” – with can occupy the interested reader for the major part of a year. We are left with threads hanging loose which, in The Golden House, are burned off for the lack of an appropriate knot.

Shantam Goyal is a Writing Tutor at Ashoka University, while also doing his M.Phil from the Department of English, University of Delhi.

‘The Golden House’ by Salman Rushdie is published by Penguin.