It’s become received wisdom at this point that the history of Indian ‘Hinduism’ and ‘Islam’, imagined as monolithic entities, are irreconcilable. The firmest ‘evidence’ of this comes from uncompromising Persian-language court chroniclers, singing of the defeat of “infidels” in rising courts—such as the Delhi Sultanate in the 13th century.

But as we look beyond, into the regions that eventually became the Hindi heartland, a more surprising picture emerges. Most medieval Hindus and Muslims didn’t follow the hostile rhetoric of courts; they inhabited a world of Awadhi Sufi epics with Hindu protagonists, which paid homage to ancient Indian mythological tropes. For all their rivalries and arguments, the line between Indian religious strands was rarely as clear as we think—whether Buddhist and Brahmin, or Sufi and Yogi.

‘Hindu’ substrate in a Sufi epic

Medieval society was enormously diverse, and extended far beyond the reach of courts and cities. Pastoralists, wandering traders, mystics, craftspeople and agriculturalists made up the vast majority of the population. Dalmau, today a town between the urban centres of Kanpur and Prayagraj, was once controlled by Ahir pastoralists before its conquest by the Delhi Sultanate.

Late in the 14th century, as the Delhi Sultanate gave way to smaller regional Sultanates across northern India, astonishing new Muslim texts appeared in the historical record. Many were written by Indians who sought initiation from Sufi masters. One of these texts—perhaps one of the most important ever composed in North India—was called the Chandayan. It was written by Maulana Daud, an Ahir pastoralist-turned-Sufi. “I cast my sins into the Ganga,” wrote Daud, at the beginning of his new text. “I became aware of the written word’s power—sang a Hinduki song in Turki script…by serving Shaikh Zainuddin, evil is forever destroyed.”

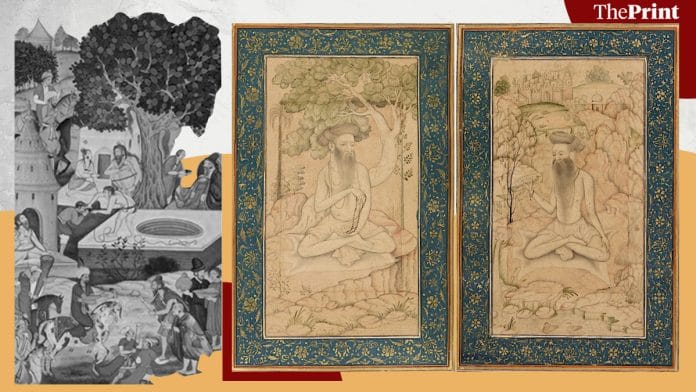

These lines above come from a painstakingly collected new volume of the Chandayan (Marg, 2024). According to the translator, philologist Richard Cohen, the lines above show that it originated in a cultural context we can think of as “Hindu”, above which Sufism had become a major strand of elite devotion. The Chandayan’s story follows two aristocratic lovers, Chanda and Lorik, whose illicit affair brings them into conflict with society and propels them into many adventures. As art historian Naman Ahuja points out in his erudite introduction to this volume, lovers’ travails are a central theme of many of the great Sanskrit epics: think Dushyanta and Shakuntala, or Nala and Damayanti.

The Chandayan’s long, winding narrative was almost certainly borrowed from wandering Ahir bards, and it reflects popular tastes. Battles between dashing heroes, raunchy sex scenes, astrologers and prophecies. It has all the elements of great South Asian romances: cunning attendants, wronged wives, heroes disguised as mendicants. But it also has subtler Sufi ideas, requiring a master’s teaching to understand. The hero, Lorik, is named after the Sun, while the heroine, Chanda, is named after the Moon. Her maid is named after Jupiter. It’s possible to read the text as the coming together of the Sun and Moon under the auspices of Jupiter. Though Lorik fights many battles through the text, they’re for increasingly selfless reasons, suggesting the soul’s journey toward God.

As Prof Ahuja has written, Sufis at the time attracted a wide following, from communities with both “Hindu” and “Muslim” traditions. The Chandayan was intended to tell them a good story while having more esoteric layers for those who took Sufi initiation. Many great Indian epics—the Hindu Ramayana, Mahabharata, the Jain Prabandhachintamani, and Buddhist Jatakas—similarly had beginnings in popular legends. They, too, later received aesthetic and philosophical treatment by monks, poets, and Brahmins. From this perspective, in basing the Chandayan on popular ballads, Indian Sufis were very much following Indian Hindu, Buddhist and Jain precedents.This makes it a landmark in our understanding of popular Islam in the medieval period—and opens up many interesting questions.

Also read: How Buddhists lost out to Brahmins in Nalanda. Even before the Turks came

Sufis and Yogis—rivalries and translations

Just as Indian Hinduism had many strands, so did Indian Islam. Maulana Daud’s Chandayan was popular among the Chishti order of Sufis, popular in Delhi and Ajmer. The Chishtis had limited political aspirations. Elsewhere, Sufi masters did have political aspirations, and did not hesitate to use violence to get it.

At the same time as the Chandayan was being composed in the Gangetic Plains, Kashmir saw the ascent of an uncompromising lineage of Iranian Sufis. These men were far less interested in local epics, and concentrated much of their efforts on converting yogis and temples into Sufis and mosques—sometimes violently. But as I pointed out in an earlier column, they presented conversions as resulting from debates and magical competitions—which proved the superiority of their tradition over others. At least rhetorically, this is reminiscent of the tenor in which Buddhist-Brahmin debates were once conducted. After establishing their ascendance, Brahmin texts often presented Buddhists as misguided heretics incorporated into their superior tradition—just as Sufis did to yogis.

But other strands of Sufism sought inspiration and ideas from yogic tradition. In Refractions of Islam in India: Situating Sufism and Yoga, historian Carl W Ernst documents many examples, especially in Bengal and Punjab. In Bengal, for example, the tantric yogic view of the body was the basis for much Sufi literature, complete with chakras and the nectar of immortality. In tantric traditions, the body has seven chakras, each associated with a god. Sufis identified the chakras with mystical stations, swapping out the gods for angels.

Indeed, Sufis and yogis had a great deal in common: both used breathing exercises and chanting for spiritual experiences; both refused to recognise caste distinctions, and both were buried instead of cremated. Wandering yogis stayed at Sufi dargahs, and both traditions exchanged not only ideas but stories. According to Refractions, a report collected by Ernst in 1998, yogis at Gorakhpur claimed the Prophet Muhammad was a Nath Yogi. Claiming another religion’s founder as a member of one’s own is quite a tradition in South Asia. Vishnu worshippers had claimed both the Buddha and the Jain teacher Rishabha as avatars of their god. For example, the 16th-century Sufi master Muhammad Ghawth Gwaliyari, in his Persian translation of an Arabic translation of a Sanskrit yogic text, claimed Gorakhnath was the Islamic prophet Khizr.

Also read: Kashmiris took Buddhism to the West—when Mongol rulers imported them to Iran

Indian Islams

Gwaliyari’s text, the Bahr al-Hayat, is remarkable in many other ways. At one point, he even calls on the tantric goddess Kamakhya to clarify a particular yogic posture. His work was composed in Gujarat and reached the Deccan, Mecca, North Africa, Turkey and Indonesia. Indian Sufism, itself composed of many distinct traditions, was in turn a distinct, powerful body within the wider Muslim world.

Its engagement with Sanskritic and popular traditions wasn’t a one-off either. In The Many Lives of a Rajput Queen, historian Ramya Sreenivasan studied the Padmavat, a 16th-century Sufi text that served as the basis for a 2018 Bollywood film. The Padmavat was, in turn, based on oral legends about the Delhi Sultan Alauddin Khilji. Though Bollywood depicted him as a half-demented barbarian, the Padmavat originally used Khilji as a metaphor for worldly illusion, while Rani Padmavati, the unobtainable target of his lust, symbolised wisdom.

Such absurd misrepresentations of Indian Muslim history have become all too typical. Indian liberals have tended to paper over the violence associated with kingship, which sometimes romanticised Mughal kings in particular (Think Jodhaa Akbar, or Mughal-e-Azam). This view has now been replaced with far-Right mythmaking that all Indian Muslims were genocidal, alien invaders—based on a handful of courtly texts, usually written by bigoted immigrants.

But regional language traditions reveal a vast Indian Muslim world, securely rooted in Indian myth and tradition. Indian Muslims engaged with popular tradition in the same way that Buddhists, Brahmins and Jains once had. In many cases, they even shared the same divinities as their Hindu counterparts. Like all Indian religions, Islam has squabbled and fought violently with others. And when they had the might of a royal court behind them, Indian Muslims could be as iniquitous as Indian Hindus or Indian Buddhists. But medieval rhetoric doesn’t justify modern policy. In both open-mindedness and in occasional persecution, throughout history, Indian Muslims have been as Indian as any of us.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian. He is the author of Lords of the Deccan, a new history of medieval South India, and hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. He tweets @AKanisetti. Views are personal.

This article is a part of the ‘Thinking Medieval‘ series that takes a deep dive into India’s medieval culture, politics, and history.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)