Writings on the Wall is a metaphor that grew out of my travels, mostly through the poll-bound regions of India and the neighbourhood over the past 15 years. Because, even more than its big festivals, the subcontinent comes to life during its elections. And what’s on people’s minds, their aspirations, joys, concerns and fears, you can pretty much understand by reading these writings on the wall. These can be graffiti, advertising, skylines, fences, piles of rubble.

Or even a solitary bull. In glorious patches of black and white.

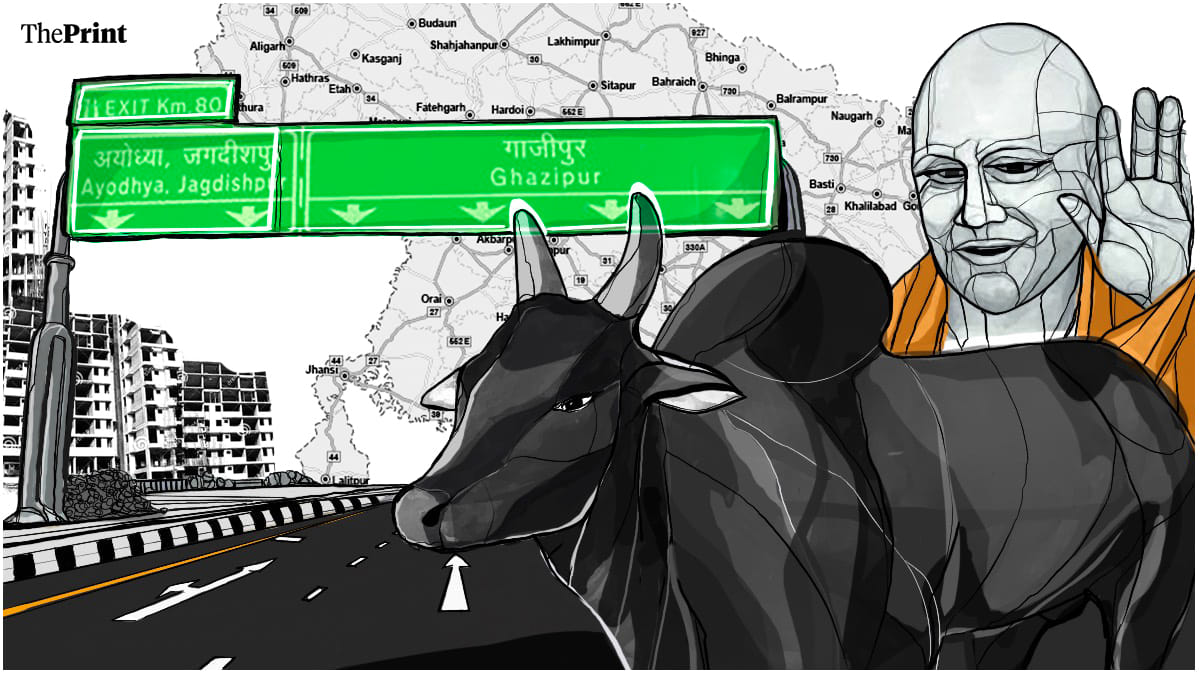

It has to say something for the way politics is playing out in the 2022 election campaign in Uttar Pradesh that the first of the ‘writings on the wall’ that catches our eye is a bull. A real bull, not as in the many, mostly rude, metaphors drawn from it. It looks down at us from a couple of hundred feet up. Its all-black hump rising into the skyline, a little like just anything that looks prominent and ornamental, placed as a canopy on top of a typical Hafeez Contractor skyscraper. It stands on top of the interchange on the new Purvanchal Expressway, as we turn left from underneath to drive into Ballia district. It looks curious, although we can be sure it has no idea it has now become a key factor in this poll campaign. A factor significant enough to help upend some recent presumptions.

Chhutta saand (vagrant bull) or simply chhutta pashu (vagrant cattle) is now a part of almost every political conversation. Cow slaughter has been illegal in Uttar Pradesh since 1955, but strict implementation of the law over the last five years has changed the picture. The sentiment, that Yogi Adityanath’s police might let you get away with the murder of a human but not that of a cow, cuts across party loyalties. Just that the BJP’s committed voters often say it with appreciation, not disapproval. But for most others, especially the smaller farmers, it is a nightmare. Unable to sell old cattle that no longer yield milk or calves, farmers push them away to roam the countryside. Sometimes, like our Mr Bull, they can end up on top of elevated expressways.

The stray bovine has now become a case study of the law of unintended consequences. In the past, most non-yielding cows were not sold for meat locally. But traders would buy these in bulk and take them to regions where beef eating is still legal. The Northeast for example. But in Yogi’s UP, even trading in cows was suicidal. Hungry cows discarded by UP’s mostly poor farmers stayed in the state. A tricky question one of our interlocutors on the outskirts of Varanasi asked, how come this isn’t such a problem in Bihar? The answer came from a journalist who knows Bihar better. Nitish is more practical. He’s ensuring there’s no slaughter, but is allowing the trade.

Cow slaughter (by Muslims, of course) is now absent from the BJP campaigners’ pitch. If in five years, cow protection has lost its oomph, and the stray cow menace is an issue, it tells us that politics changes all the time. Even in the Hindi heartland, where we might have thought it was frozen after the three BJP sweeps. In 2014, campaigning for his first term, Narendra Modi had thrown opposition to ‘pink revolution’ (meat exports) and made a key proposition.

Buffalo meat exports (pink revolution) are steady. But stray cows are now a liability to the extent that in the later stages of the campaign, Yogi is promising a monthly cash dole to those owning non-yielding cows.

This is no game-changing issue. It isn’t as if stray cows will determine the outcome of this election, or have already done so. But it’s among the many factors that carry weight in that perpetual post-1989 tussle in the heartland. Can you unite with religion (Hindutva), what caste divided, or can caste again divide what religion united?

Also Read: Let them eat communalism: Yogi’s poll pitch may work but heartland’s jobless fury endangers India

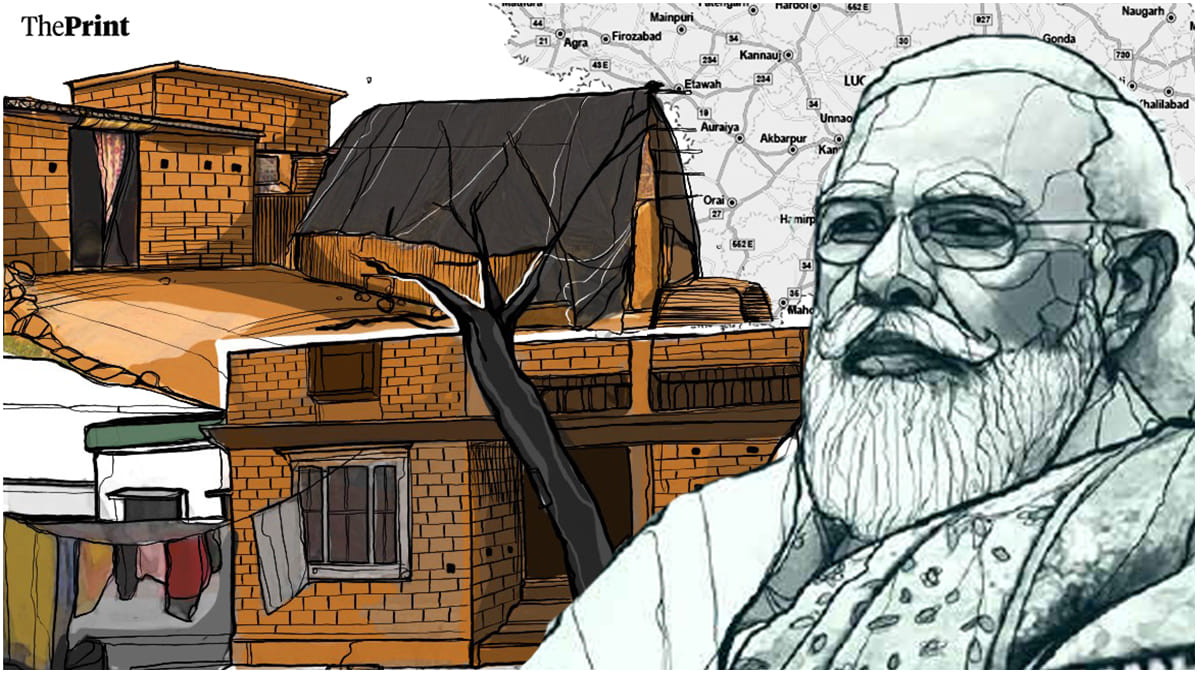

Sonbhadra isn’t the poorest district in Uttar Pradesh, although in most parts you wonder what a poorer one would look like. The poorest and most backward, not just in UP but in all of India, is Shravasti, almost 400 km away, generally to the north.

Maybe Sonbhadra’s data is deceptive because it has enormous mineral resources, and major power and cement plants. Incomes from these can distort overall averages. But in reality, its people are beaten down by a crippling resource curse, as mafias fight over its lands and mineral-laden hills. Not very different from the contiguous zones of the four states it borders: Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Bihar and Madhya Pradesh. Forty per cent of the district is tribal. In July 2019, 10 Gond tribals had been massacred by the land mafia, as reported by Simrin Sirur here.

At his rally at the grounds of an engineering college outside district headquarters Robertsganj, Prime Minister Narendra Modi seems to have sobered his message knowing Sonbhadra’s reality. In a district with a huge hydroelectric project and some of India’s oldest large power plants, his pitch isn’t about more factories, growth, jobs. It is mostly about free food grain. Did any of you have to starve during the period of pandemic? I, he uses first person singular, made sure food grain was sent to 80 crore poor people in the country so no one would starve. Are you all vaccinated? No Hindu-Muslim, and Yogi too finds only one passing mention in the very beginning.

You can say this isn’t quite the BJP’s territory. Given the large tribal and OBC (Kurmi, Patel, Kheri, Kushwaha) population here, the dominating party is the regional Apna Dal (Sonelal) of Anupriya Patel. The MP from here, Pakauri Lal Kol, a tribal, is also from her party. So that might explain the absence of enthusiasm or spark in Modi’s modest rally. But, three of the district’s four MLAs are from the BJP. And it is important enough for Modi to make a stop here.

In a phenomenon we might remember from even the glory days of Indira Gandhi, but haven’t seen in Modi’s rallies, people begin to slowly melt away as he begins to speak. It’s odd, but maybe it is too hot at 2 in the afternoon.

Conversations at the Dalit basti in Genduria village, a few kilometres down the state highway to Varanasi, probably give us some clue. Everyone, every adult in the clump of about 50 houses, is unemployed. Most have some education, several intermediate (Class 12) pass. Some have been unemployed for a decade, since they finished junior college. The government is not hiring, industry is not expanding, many had gone to work in distant states.

Like Panchmukhi Sonkar, 30, who worked in Goa, first at a toothpaste factory and then at an automobile puncture-fixing shop. He’s set up a kuchcha tea shop, but there are no customers because no one has any money. Like all others in the huddle, he survives on odd jobs at brick kilns and construction sites, carrying bricks and sand.

Panchmukhi sold vegetables to pay for his education. Chandan Kumar, also a Dalit Jatav, scrounged and worked on the side to pay Rs 80,000 for his diploma as a pathology lab technician in Varanasi. But then the government said it does not recognise the diploma. He’s grateful he’s found a low-paying job in a local private hospital. How does he hope to live better, or less worse? By working two eight-hour shifts a day at the hospital. You can watch his story here.

Another 20 km down the same highway, we halt at Juri village, also a clump of thatched huts with the odd brick structure here and there. In local discourse, it is called an ‘Awas’, as in built from funds under PM Awas Yojana for the below poverty line (BPL) families. The family at the thatched house next to an ‘Awas’ is from the Maurya community. This is an OBC hamlet with a mix of Kushwahas, Koeris and Kurmis, who almost uniformly say they voted for the BJP/Apna Dal the last time. But there is some rethinking now. Listen to Deepa Maurya, a Class 10 student, and her mother. Again, a story of no jobs, menial labour, no money yet for an Awas house, and the compulsion for her to go to a fee-charging private school, since the free government school is too far. Will she study further? I want to study “daaktari” (medicine, to be a doctor). But… You can listen to the family here.

The story plays out similarly. These people are among the largest non-Yadav OBCs. In the last three elections, the BJP has aced their vote. Now, the picture isn’t so comfortable for it. “Kya karein, jo saat saal pehle berozgar thha, abhi bhi berozgar hai,” (what to do, one who was jobless seven years ago is still jobless) says Babu Lal Kushwaha. Joblessness is the new caste, to be ‘bekaar’ or unemployed is the new identity that cuts across the conventional ones.

Also Read: Modi at 71 has zero challenge. But one CM is emulating him, a divisive, rising BJP star

Jobs, jobs, jobs. That is all you see written on the wall of placards waved by a near-stampede of mostly young people at Akhilesh Yadav’s rally in Nagra near Ballia, as you can see in this video. Some placards want those selected for the police in 2017 given appointment letters, some want teachers’ recruitment exams held, some for paramedical staff and so on.

Lack of jobs is a grievance common to these educated young. There is still some sense of humour though. Placards read: B.P. Ed Exam, now in year 3202. This is the kind of energy we rarely see in an election rally these days, except when Modi is campaigning with himself on the ticket.

Akhilesh finds a few minutes to chat with us even as the stage is being shaken perilously by surging crowds. Much of Modi’s attack on him lately has been over ‘parivarvad’ (dynastic politics). Would Yogi Adityanath have become the head of his religious order, Akhilesh asks, if not as a mere successor to his mama (maternal uncle), who held the position earlier? He would’ve spent his time being jobless like so many others here, he says.

In Mau, the ‘karmabhumi’ of many rival dons, but mostly of Mukhtar Ansari (jailed for some time), we find his son Abbas, a former international shooter and a winner of seven national medals in his chosen discipline, skeet. He describes to us how his career was cut short as the state government filed multiple cases against him, and once criminally charged, you can’t represent India. I am a shooting champion, he says, and they filed an Arms Act case against me.

The Yogi government’s claim of improving law and order, he says, is all baloney. It’s so selective and communal, he alleges, that Brijesh Singh, who is jailed in Varanasi on the charge of carrying out a massacre in Mumbai’s J.J. Hospital with AK-47s, has to approve every real estate deal in the region. And you know what, Abbas says, Yogi visits him often in jail and spends hours deciding on candidates and politics. All he’s doing is targeting us minorities, even me, the great grandson of the great 1948 war hero Brig. Usman, the Lion of Nowshera. Mayawati echoes the same point too. Has the Yogi government taken the bulldozer and hammer to any non-Muslim property, she asks us in a short conversation after her rally near Varanasi.

In all BJP marches, rallies, one chant stands out. Bulldozer baba, Jai Shri Ram/bulldozer baba zindabad. In his speeches, Yogi too uses the bulldozer as a dog whistle. At a rally at Baldev Inter College in Varanasi’s Baragaon neighbourhood, the only times he gets the crowd charged is when he mentions the bulldozer, hathauda (hammer) and SP’s idea of development merely being raising the walls of kabristan (graveyards). But you know what, people have heard him say all this before. Within two minutes of him beginning to speak, there is an exodus. You can watch it here. To be fair, everyone we speak to says they will vote for BJP. But good words they have are all for Modi, not Yogi.

Here is the big picture in these Writings on the Wall. Caste is back, after 2014, 2017 and 2019. Joblessness is the new nationalism and religion. Too many poor people are hurting as they pay for cow protection. Most of the upper castes, especially shopkeepers and traders, say they are stressed, but would continue voting BJP because it improved law and order. A lot of the poor acknowledge free grain, pulses (chana) and edible oil. The decision to vote will be crunched through these sometimes-contradictory emotions.

Sounds confusing? It only means it is a more ‘normal’, fiercely contested election in Uttar Pradesh after three walkovers for the BJP.

Also Read: Can 2024 become more challenging for Modi? Yes, but it’s all up to Congress