The World Bank’s food security update of August 2022 flagged how global concerns over the likelihood of a rice export ban by India are rising. It noted that “exporters, concerned that export restrictions will be introduced (as has been done for wheat), are moving quickly to open letters of credit and have signed contracts to export 1 million tonnes of rice from June through September 2022.” But are these concerns real? Is there any cause for worry in the case of Indian rice? Our estimates show that even though there is no palpable threat to India’s food security, the window of Indian rice exports this year may be constrained.

In 2021-22, India produced about 130.29 million metric tonnes (MMTs) of rice. About 86 per cent of this (about 112 MMTs) was produced during the Kharif season (sown during June/July and harvested during November/December). The remaining 14 per cent was produced in the winter months during the Rabi season.

As per NITI Aayog’s demand and supply projections, India’s projected consumption in 2022-23 will be about 108 to 109 MMTs of rice. In addition to the central pool stocks of rice with the government, the private sector also maintains some stocks of rice that move between crop years. But, if we assume for the sake of understanding, zero opening and closing rice stocks, then it appears that last year, the country generated a surplus of about 22 MMTs (130.29 – 108.28). This was approximately the amount of rice that was exported from the country last year. However, this will not be the case every year, as stocks both with the Food Corporation of India (FCI) and the private sector play an important role in India’s rice balance sheet.

Also read:

Problems for India’s rice crop this year

This year, there are news reports of lower paddy acreage and yield. But it is not just the area coverage that is lower than last year. There are reports of the drying of transplanted paddy crop in fields primarily due to lack of irrigation. Inter alia, there appear to be three reasons for this. First, deficit rains in key paddy growing states of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and West Bengal, which produce about one-third of India’s paddy. Second, dwarfing of rice plants caused by a Southern Rice Black Streaked Dwarf Virus (SRBSDV) attack and third, more remunerative price incentives for sister crops like soybean, and cotton.

Kharif is the main cropping season in India and it pivots on monsoon rains. About 52 per cent of India’s gross cropped area has assured irrigation, as per data from the Ministry of Agriculture. This implies that about 48 per cent area depends directly on monsoon rains for irrigation. Even in irrigated areas, rains are needed to reduce dependence on electricity and diesel. So, if there is serious deficiency in rainfall, the crop production and its costs of cultivation are bound to be adversely impacted.

As of 29 August 2022, India’s monsoon showers are about 7 per cent above their long-period average value (LPA). Interestingly, the LPA value has itself been adjusted downwards this year in light of shrinking volumes of Indian monsoon rains over time. Despite a good monsoon figure at an all-India level, six states/Union Territories have received deficient rains. These states include Uttar Pradesh (with a rain deficit of 44 per cent), Bihar (with a deficit of 39 per cent), Jharkhand (deficit of 26 per cent), Manipur (deficit of 44 per cent), Tripura (deficit of 28 per cent) and Delhi (deficit of 31 per cent). Until recently, West Bengal was also in this category. However, a recent spurt in rains has pulled up its rain measure, though it still shows a deficit of about 18 per cent.

Not just deficits, this monsoon season has also seen instances of floods, like in Madhya Pradesh, and increased intensity of rains in a shorter span of time, like in Maharashtra.

To counter the lost time, many farmers in states like Bihar and UP have shifted to shorter duration varieties of paddy and many have even shifted to cultivating pulses like moong which require lesser water for irrigation. All this has led to lower acreage and lower expectations of paddy yields this year.

Apart from rains, virus attacks in the northern states of Punjab and Haryana are reducing tillage in paddy crops. For farmers in some areas in these states, this is double trouble. First, wheat suffered shrivelling due to historical levels of heat during the critical harvest months of March and April 2022 and now the paddy crop is infested with the virus. Thankfully, the virus attack is limited to only some regions of the states. But for some cotton farmers of Punjab, the virus may actually be kicking-in the third bad crop cycle after their cotton crop was badly damaged due to the pink boll worm attack in October 2021. This year is emerging as exceptionally difficult for them. Punjab produces about 10 per cent of India’s paddy and the impact of the virus on rice crops is yet to be determined by the scientists.

Overall, it appears that India’s paddy crop this year is likely to be smaller than last year. Our ongoing market assessments and media reports suggest the loss may be anywhere between 10 to 15 per cent.

Also read: India has a dal problem – open import policy is hurting prices and farmers

Projecting Indian rice balance sheet for 2022-23

Using the same rice balance sheet approach, we estimate the ‘window of exports’ this year. We create scenarios of production estimates and use them to estimate the availability of paddy in the system in the current year. Upon comparing availability with domestic demand for paddy, we estimate the residue in the system, which we refer to as the ‘window of export’ for the country. In our base case, we assume the current year’s crop to be the same as last year’s (130.3 MMTs). Based on our ongoing market assessments, we then introduce shocks to the Kharif paddy production (10 per cent, and 15 per cent) and create three scenarios (Table 1).

Based on these estimates, we find that unlike 2021-22, when India exported about 22 MMTs of rice, India’s rice export window for 2022-23 will be much smaller, somewhere between 12 MMTs and 17 MMTs.

We have made a few assumptions: one, paddy allocations under PM Garib Kalyan Ann Yojana (PMGKAY) would discontinue from September 2022 onwards. Two, the Indian government will only be holding paddy equivalent to the buffer stock norms by October 2023 and three, Rabi paddy is likely to stay the same as last year.

If the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana (PMGKAY) does discontinue, then the open market availability of rice for exporters will reduce, shrinking the export window further. And if rice procurement follows the pattern of the previous three years (procuring about 50-60 million tonnes of rice), resulting in higher stocks than the buffer norms, the window would shrink yet further.

Also read: Inflation pinching your pocket? There is more in the pipeline. But god can help

Situation on domestic inflation in rice

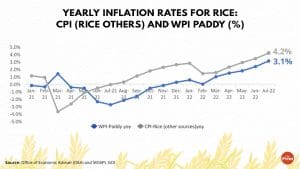

Even though low, domestic rice price indices have been fast in gaining upside momentum. (Figure 2).

Also read: India is splurging big time on airlines, roads & railways. Let’s just hope it all pays off

No cause for panic

The year 2022 is emerging to be unique for Indian agriculture. Both the staple crops of rice and wheat appear to be suffering production losses.

The above projections show that even though the rice export window appears smaller this year, there does not appear any threat to the country’s food security. Besides, we need to remember that India has a Rabi paddy season too, unlike wheat, which only gets sown during winters. Though only small, Rabi paddy can cover some gaps in Kharif paddy.

However, September is a critical month for paddy as it is also the month where the crop is most susceptible to pest attacks. How the crop performs this month will have to be closely watched.

Also read: Cotton, other crops shouldn’t meet fate of wheat. Govt needs an empowered group

Some policies need rethinking

We think that releasing rice from FCI stocks for meeting targets under the ethanol blending program is ill-advised. In view of climate change emerging to be a reality, India needs agility and realistic policies. The release of timely and accurate data can supplement efforts of the government to tailor the policies to emerging scenarios so that knee-jerk reactions and sudden restrictions under the Essential Commodities Act are avoided.

The damage to wheat crops due to excessive heat in March and erratic monsoons in large rice-producing states has again shown that climate change cannot be wished away any longer. Therefore, the government policies have to ensure that the farmers are given advisories well in time, depending on the climatic conditions. Policies on production, procurement, trade, import and export have to be fine-tuned with agility so that the emerging scenario from adverse climatic conditions are taken into account expeditiously. Funding for the National Initiative on Climate Resilient Agriculture (NICRA) needs to be enhanced so that better seeds are developed to withstand climate extremes.

Both Saini and Hussain are co-founders of Arcus Policy Research. Views are personal.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)