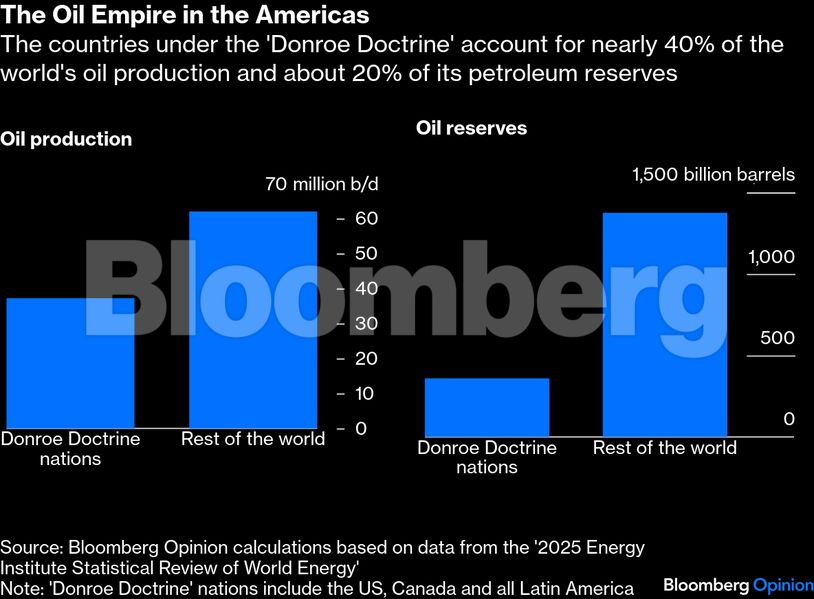

Let’s do the math. Start with the oil production of the US and add Canada. Then include Venezuela and the rest of Latin America, from Mexico to Argentina and everywhere else in between: Brazil, Guyana, Colombia. Like it or not, all of them are living under the “Donroe Doctrine” — an increasingly belligerent Washington’s sphere of influence over the Americas. Together they account for nearly 40% of the world’s oil output.

Then it’s a choice of language to describe what the US administration will do with all those barrels. It may try to exert direct control as in Venezuela, or oversee, influence and simply enjoy the benefits of what’s produced. Whatever the word, President Donald Trump now has his very own oil empire.

And I’m talking about actual barrels already flowing into the market, not underground reserves that would take time and money to be developed. With such resources Trump has an economic and geopolitical lever no US president has had since Franklin D. Roosevelt in the 1940s. At home and nearby, his country can tap a vast sea of oil.

The implications of getting unfettered access to Venezuela’s reserves, the world’s largest, were immediately apparent to anyone in the energy and commodities business, particularly American foes. Oleg Deripaska, a US-sanctioned Russian oligarch, put it well on Saturday: Washington would have the means to keep the oil price close to $50 a barrel — giving it a winning hand in the future against anyone threatening to push the price higher by curbing supply. The Kremlin envoy Kirill Dmitriev said seizing power in Venezuela offered “huge leverage” over the global energy market.

Having de facto control of the Western Hemisphere’s petroleum wealth is a geopolitical game changer. For decades, US military adventurism was constrained by the impact of any war on energy costs. Today the White House has primacy over oil-producing allies and adversaries alike — whether it’s Saudi Arabia or Iran, Nigeria or Russia.

The past 18 months have already shown what these new hydrocarbon riches mean for US foreign policy. Trump’s administration has taken once unthinkable steps: from bombing Iranian nuclear facilities to helping Ukraine target Russian oil refineries. Grabbing Nicolas Maduro from his safehouse in the outskirts of Caracas was the most shocking example yet of what happens when oil doesn’t constrain the Pentagon anymore.

And seizing Venezuela’s oil gives the US another card: the ability to decline offers for access to petroleum riches. For months the Kremlin has dangled its own reserves as a carrot in talks with the White House. Trump can now tell Vladimir Putin he doesn’t need his Siberian fields. He has more than enough.

Don’t give Trump all the credit, or even most of it. He’s in power at the right time. American oil would be booming without him thanks to the riches of US shale, Canadian heavy oil and discoveries in places like Brazil and Guyana. Ex-presidents Joe Biden and Barack Obama benefited, too.

What Trump has done is pull all of that petroleum under Washington’s security umbrella. More than 200 years after US President James Monroe declared Latin America a sphere of influence for the White House, creating the Monroe Doctrine, Trump is updating it for the 21st century, hence the half-joking Donroe label. This time much of it is to do with natural resources.

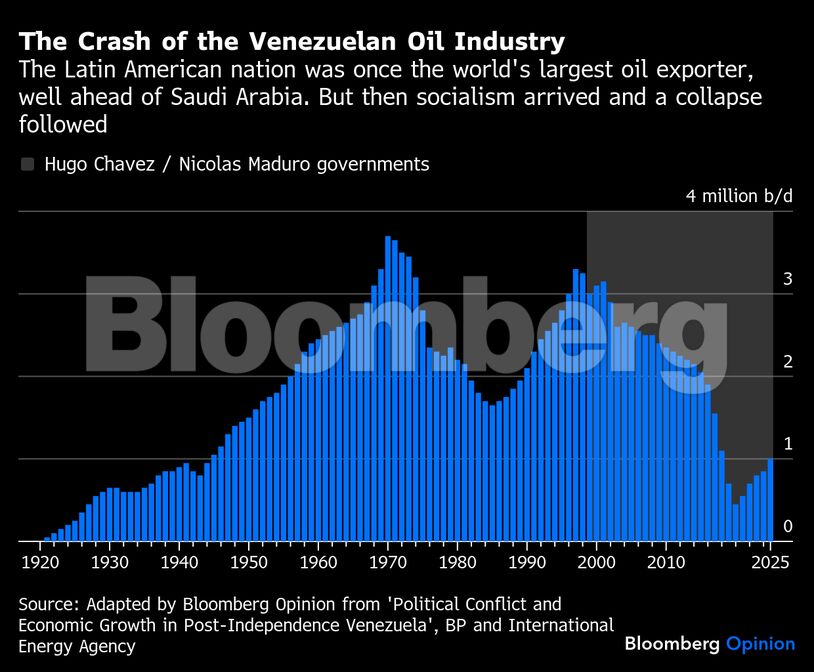

For the new US foreign policy, every oil-rich nation in Latin America is important, but the prize of Venezuela is enormous. This isn’t because of its current production: At about 1 million barrels a day it pumps significantly less than Brazil. It’s because of what it once produced — more than 3.7 million barrels a day at its 1970 peak – and could pump once more.

The geology is there. All that’s needed to unlock the nation’s oil wealth is capital, time and effort. At one point in the 1990s, Caracas had a plan to boost output first to 5 million barrels a day and then to 6.5 million. The arrival of Hugo Chavez, followed by Maduro, put an end to that. Can Venezuela once again target those levels? Sure. Would they be achieved soon? A hard no. Can it be achieved in the next five years? Also unlikely.

But the world doesn’t need the extra Venezuelan oil today, or next year or even in 2027 and 2028. It would be needed in the early 2030s. And by then, if Trump is right that Caracas will play ball, Venezuelan oil production can be far higher.

In many ways the post-Maduro order that Trump appears to be aiming for — letting the regime’s former number two Delcy Rodriguez assume power for now in a soft dictatorship, or “dictablanda” – works fine for US oil companies. She has already stabilized her country’s economy by applying some market orthodoxy. For now, ignore her protests about the American attack. Much of that’s for a domestic audience.

Trump, clearly, has high expectations of her. “We’re going to have our very large United States oil companies — the biggest anywhere in the world — go in, spend billions of dollars, fix the badly broken infrastructure — the oil infrastructure — and start making money for the country,” Trump said in a Saturday press conference. Hours earlier in an interview with Fox News he said the US was going to be “very strongly involved” in the Venezuelan oil industry.

Over the years, we’ve learned to treat Trump pronouncements with caution. But in his second term, he’s done plenty of what he threatened to do. If he says the US will be involved in Venezuelan oil, take him at his word. Perhaps the venture won’t be as grandiose, or as profitable, as he declares. That doesn’t mean it won’t happen. The country’s oil is now part of a petroleum empire stretching from Alaska to Patagonia — all under Washington’s tutelage.

This report is auto-generated from Bloomberg news service. ThePrint holds no responsibility for its content.