India is currently testing over 100,000 samples a day for the novel coronavirus, from 1,000 a day in mid-March. This does not mean number of people tested, because some will be tested multiple times, but it, doubtless, is a significant increase and improvement. And yet, we know less about Covid-19 than we knew a month ago.

As India slowly prepares for the post-lockdown phase, it is important to release more spatially disaggregated data and clean up data systems. We have to get past the Ministry of Home Affairs’ frenetic announcements about multi-coloured zones, without any official data in the public domain about test positivity rates in the states, leave alone districts.

This is critical if we are to evolve sensible protocols to live with Covid-19, involving more narrowly defined no-go zones and early signalling of rising test positivity rate in an area. This will not happen unless the health ministry and Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) stop perpetually “reconciling data”.

All these add to why we know so little about Covid-19 infection levels in India. But it’s data we need if we wish to fight the pandemic.

Also read: Why South Asia has 20% of world’s population but less than 2% of Covid-19 cases

Muzzling the ICMR

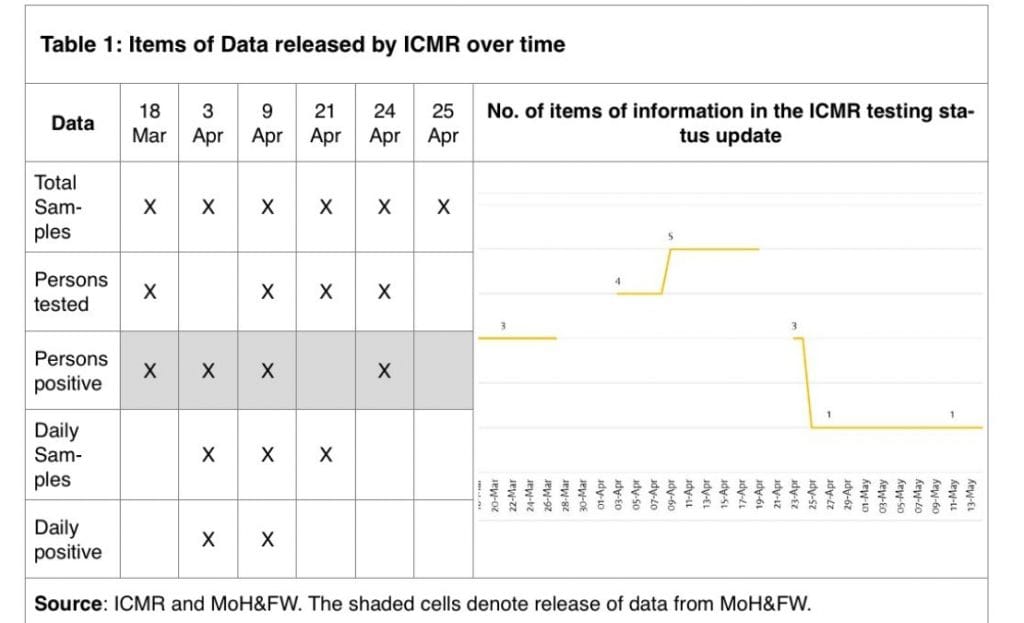

Ideally, the test positivity would be the number of persons testing positive divided by the number of persons tested, but this data is no longer released by official sources. Between 9 and 19 April, the ICMR released the most information — number of total samples tested, the number of total people tested, the number of persons found positive — but it all stopped on 25 April, and Covid-19 numbers kept increasing in India. The ICMR has since only released the cumulative total samples tested. Table 1 shows the extent of information released by ICMR at different times in the past two months.

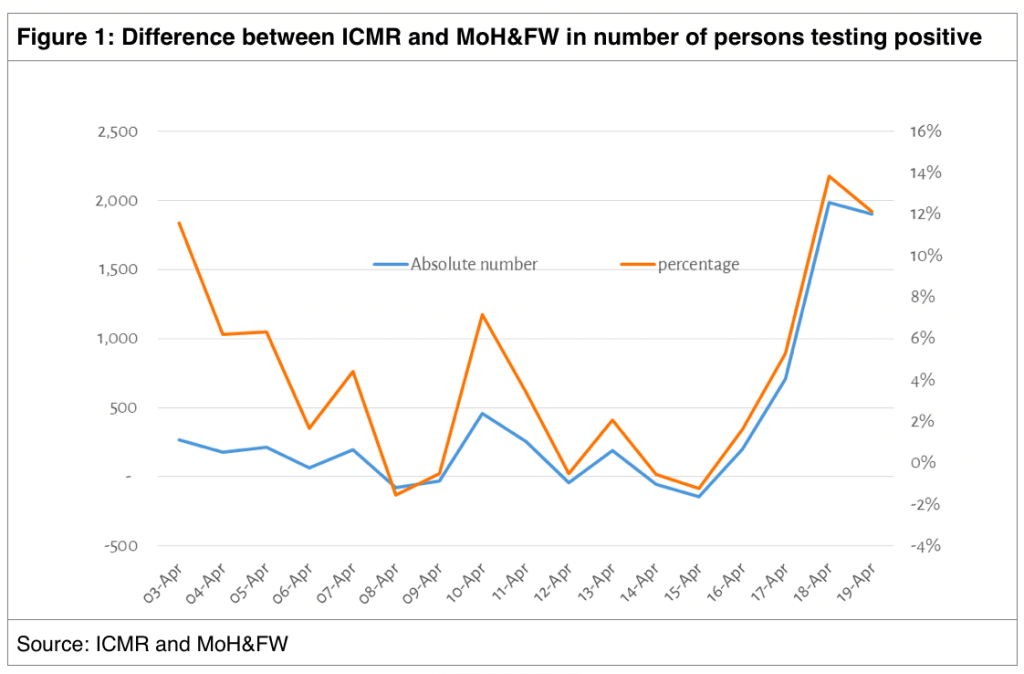

Also, the ICMR’s data did not exactly match with the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare’s, which also used to release data on the number of Covid-positive persons. After the ICMR stopped releasing such data, the health ministry website says its “figures are being reconciled with ICMR”. As Figure 1 shows, the differences were not particularly glaring and the health ministry was not consistently under-reporting numbers, despite occasional spikes.

But, the health ministry has been singularly reticent in its approach to releasing information – almost as if it believed that no news is good news. Its website has no archive of previous documents; once a document leaves the home page, it disappears – becoming as invisible as a migrant in a city. The health ministry has issued periodic letters to the states, on various procedures — for example, the classification of zones. But the health secretary’s letters, which are viral on social media, are never to be found on the health ministry’s website.

It’s a telling commentary on our systems that it has not been possible – for over three weeks – to reconcile state data with a national portal, where, supposedly every test in the country is recorded. Is it because data entry is delayed on the portal – a process improvement that should have been done in mission mode — or because the data captured by the ICMR is uneven or because government data systems are primitive?

ICMR’s data may have shortcomings — there may be misidentification of the location, duplicate records due to the multiple samples per patient, non-use of the unique ICMR ID for subsequent tests — but is anyone fixing these problems and helping states gather reliable data? As a government that touts Aadhaar as a singular national achievement, this data disarray in the midst of a public health crisis makes the exceptionalism of such top-down initiatives sharply and sadly apparent.

Also read: 3,900 new Covid cases in India: ‘Sharpest daily spurt’ but positivity rate same since 1 April

Crisis handling

The story of the ICMR’s data management is illustrative of the handling of the Covid crisis – the lack of transparency, preparation, the reluctance to engage with differences and use them as a cross-check and feedback mechanism, the obsession with narrative and the subservience of professionals and experts.

Before the lockdown, there was little sense of crisis; indeed, the initial procurement of kits started after the lockdown, in end-March. There was no integrated reporting system for various testing laboratories, and even in mid-April, the official storyline was that India’s testing strategy was “smart & focussed”, with tests conducted mostly on symptomatic people — asymptomatic infected people were missed. Since then, Dr Raman Gangakhedkar, ICMR’s head of epidemiology and communicable diseases has said: “If we look at the number of tests done, so far 31 per cent belong to the symptomatic category and the rest 69 per cent would fall under asymptomatic.” The experience of pilgrims who returned from Nanded in Maharashtra to Punjab, among whom 30 per cent tested positive, but were mostly asymptomatic, shows that much remains unknown about the coronavirus’ transmission and virulence. Humility is a better virtue than smartness.

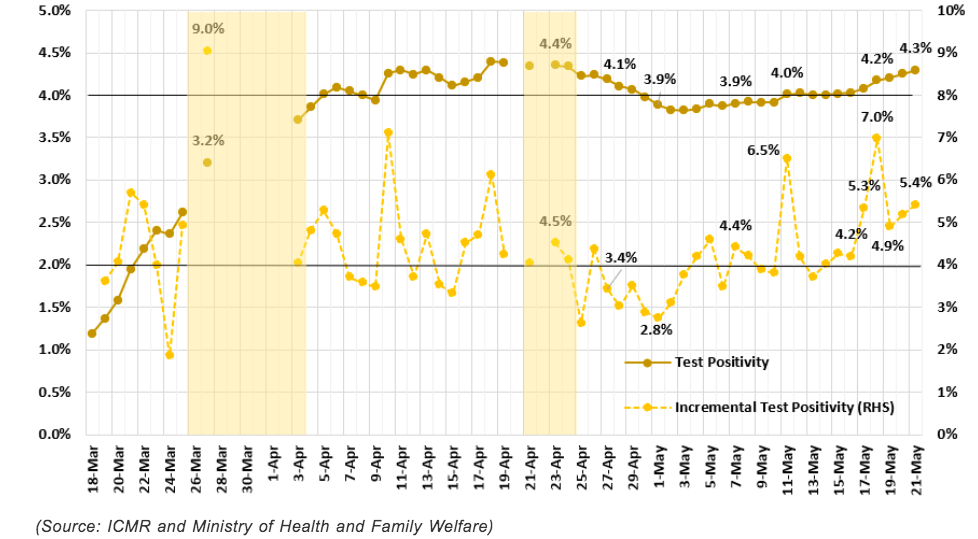

Constant positivity

Beyond data, there is interpretation. That’s also where India is failing in the Covid-fight. On 23 April, in a detailed media briefing, much was made of the constant test positivity rate. Figure 2 shows that the national test positivity rate is hovering around 4 per cent for the past few weeks, even as the incremental infection ratio – change in number of positive persons to the change in the number of tests – has fluctuated. But, what does a constant test positivity mean, as daily tests are increased 100 times? As more people are tested, one expects the test positivity to fall, but instead, proportionately more infected persons are being found. If this is happening seven weeks into lockdown, it is a matter for concern, not celebration.

Figure 2: Test Positivity for Covid-19 in India over time (this chart is as of 21 May)

One would ordinarily expect the level of infection in the population to be much lower than the level of infection among people who are being tested, since many of those tested are symptomatic patients in hospitals and a core group of contacts of people testing positive. But, a large number of people testing positive are asymptomatic.

In Maharashtra, which releases data daily, this is over 70 per cent. Are all these asymptomatic contacts? If not, why were they tested? Till we know who is being tested, in comparison to the population, one cannot infer what test positivity indicates about infection in the general population. It is not difficult for ICMR to release data on test positivity by category of people tested, which it collects as part of its form, but it does not do so.

Also read: Delhi violating ICMR, WHO norms by not Covid-testing the dead. But it’s not the only state

Churn across states

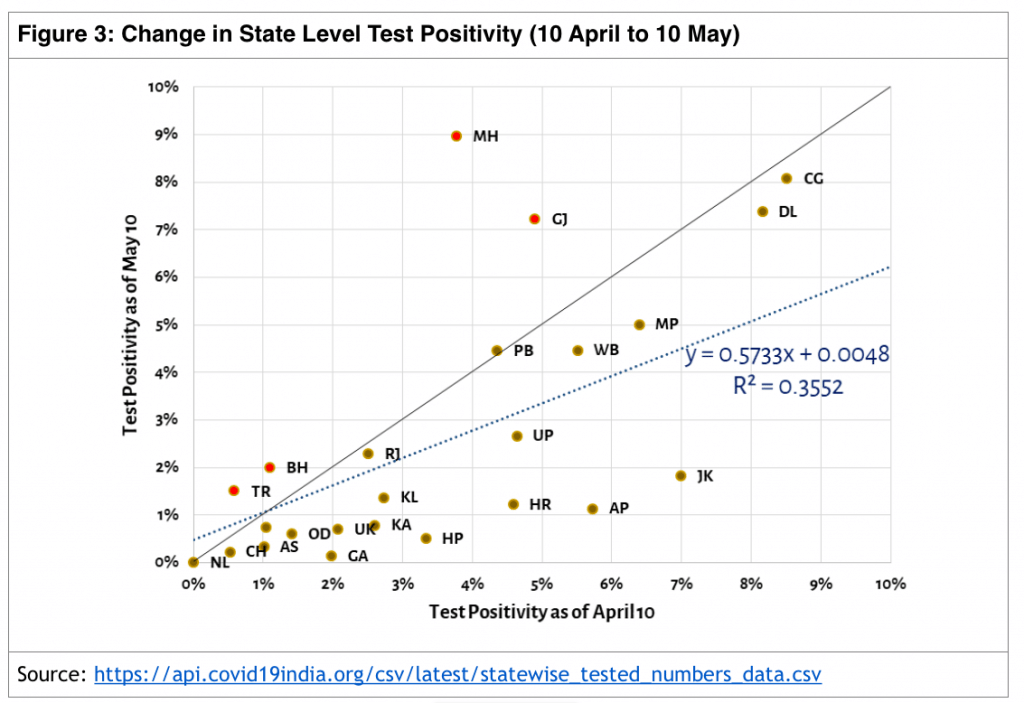

ICMR does not release any data on positivity by states, which it can, based on its testing database. So, one has to fall back on data compiled by crowdsourcing platforms from various official announcements (the number of tests is slightly higher and test positivity is a little lower in the crowd-sourced data).

Figure 3 shows that this data indicates the constancy in the national test positivity masks significant churn within the states. There is variation across states and over time. As testing increased between 10 April and 10 May, the test positivity of most states changed – most declined, with the exception of Maharashtra and Gujarat.

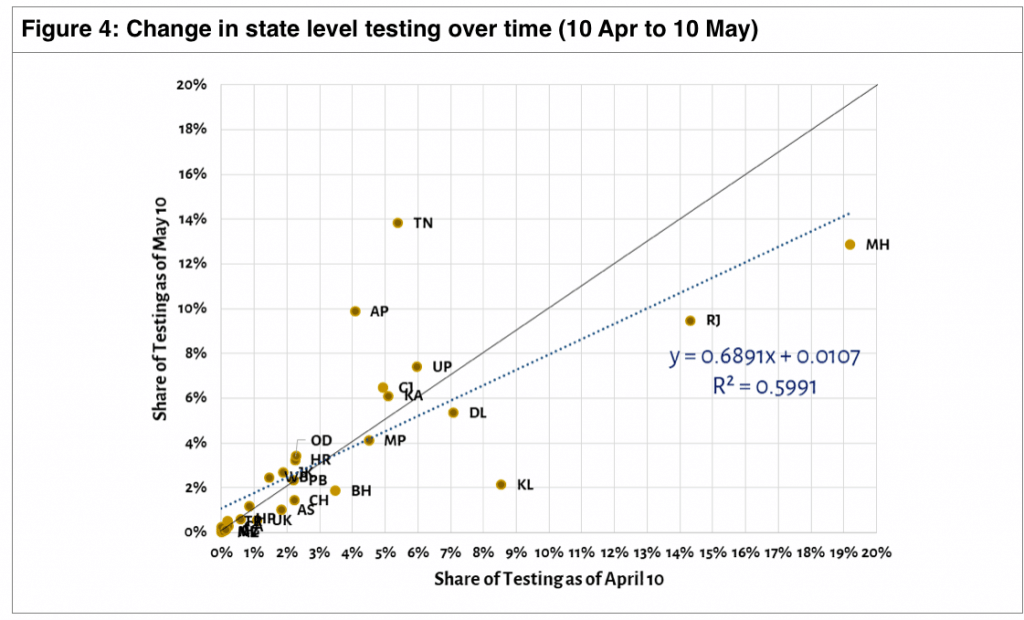

Figure 4 shows that the pattern of testing being carried out across states also changed (if all states had a common trend, the share of a state’s test to national tests would remain the same, around the 45-degree line). While Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu increased testing significantly, Rajasthan and Maharashtra, which tested a lot earlier, relatively slowed down, and Kerala bucked the trend by managing the epidemic without massive testing – if its success holds.

As India slowly lifts restrictions, it is data of infection levels that will help us shape a post-Covid world.

The author is senior fellow at the Centre for Policy Research, Delhi. Views are personal.

And what’s the point of the article? Do you even know the importance of test positive rate? Any causal modelling or correlation analysis that the author has done?

Like true to your backers,Congress Party just keep complaining so that sometime that will stick in peoples minds the false information.Shame on all The Print journalists and the chief ASS SUCKER Shekar.