Sixty years ago, India suffered a catastrophic defeat in the 1962 war against China when the Indian Army was routed in one month and one day, from 20 October to 20 November, with only 10 days of actual fighting. The entire North-East Frontier Agency (Arunachal Pradesh) and 50 per cent of Ladakh were shamefully abandoned. Rubbing salt into our wounds, China declared a unilateral ceasefire and withdrew on 21 November after it had achieved its military and political goals leaving behind neatly piled stacks of our antiquated arms and military stores.

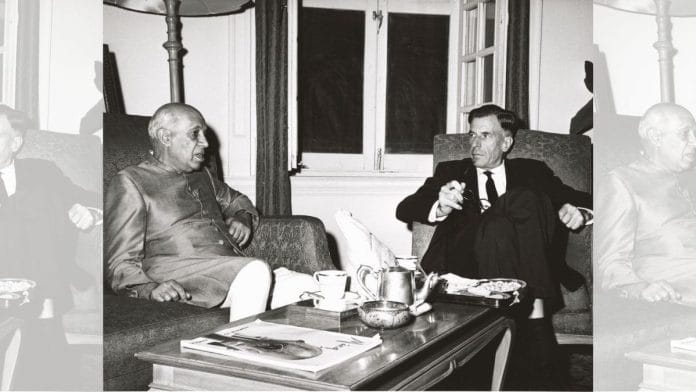

Military historians, media and the public are unanimous in their view that the responsibility for the debacle rests squarely on the shoulders of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, both for not diplomatically negotiating a settlement and for not creating the necessary border infrastructure and the military capability to safeguard our territorial integrity. Sixty years later, in May 2020, we were again engaged in a conflict in Eastern Ladakh. We no longer exercise control over an additional 1,000 square km of our territory and lack the political will and military capability to take it back. Failure of diplomacy and inadequate military capability are evident. Ironically, this time there is no accountability.

What were the drivers for the 1962 war and what started the ongoing crisis in Eastern Ladakh? What were and what are the compulsions of Prime Ministers Nehru and Modi? These answers can provide lessons for the future.

Also read: From clash at Longju to ‘Operation Leghorn’, how skirmishes built up to 1962 India-China war

Flagging the frontiers

Territorial integrity is the sine qua non for nation states, and in case of civilisation states with infinite memories, the quest to recover lost territories is omnipresent. Past agreements have little or no sanctity. India had cast away the memories of foreign invaders and the yoke of colonial rule in 1947 and China had ended its ‘Century of Humiliation’ in 1950. Separating them were the frontier regions in the high Himalayas.

‘International boundary’, ‘border’ and ‘frontier’ are geostrategic terms used to describe the space between contiguous nation states in descending order of legitimacy and international acceptance. Empirically, frontier regions are first flagged to establish ownership, then negotiations or conflicts create borders with physical military control, and finally agreements are signed to delimit, demarcate and delineate the borders to create a mutually accepted international boundary. Frontiers and borders are prone to conflict particularly when the nation states are also competing for power. Thus, both the 1962 War and the on–going Ladakh crisis on the borders were inevitable.

What we inherited in 1947 was a frontier region shaped by the Himalayan chapter of the Great Game with a dysfunctional Tibet and the semi-autonomous Xinjiang as buffer states. The frontier region was not physically secured. In the eastern sector, the border was defined by the McMahon Line which was delimited on small scale maps but not demarcated on ground. However, China had not signed the 1914 tripartite agreement (between British India,Tibet and China) that defined the line. In the western sector, the reliance was placed on traditional/customary boundaries and the 1842 Sikh Empire-Tibet treaty. However, the boundary of the Aksai Chin area along the Kunlun Mountains was shown as “undefined” with dotted lines until 1954 implying non-delimitation.

After China had secured Xinjiang and Tibet in 1949 and 1950 respectively, both sides raced to flag the Himalayan frontier. In the North-East Frontier Agency (note the name), India pre-empted China and secured the areas up to the McMahon Line by 1951 using the Assam Rifles. This was a political coup because until then Tibet exercised political control over Tawang and parts of Lohit division. In the western sector, China pre-empted India and secured three-fourths of Aksai Chin and built a road through it linking Xinjiang to Tibet. We managed to plant our ‘flag’ in the remaining region of Aksai Chin using the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) and the Intelligence Bureau (IB).

By mid-1959, our police and paramilitary forces came face to face with the Chinese border guards at varying distances east of the present-day Line of Actual Control (LOC) in the western sector and the McMahon Line in the eastern sector. Due to the revolt in Tibet and India granting asylum to the Dalai Lama in April 1959, China hardened its position and came out with a formal claim line in Ladakh, which is now known as the 1959 Claim Line. The first two clashes took place on 25 August at Longju in Lohit Division and on 21 October at Kongka La in Ladakh. It was clear that any further competitive flag-marking will lead to conflict.

Also read: ‘Expansionist’ Nehru, Tibetan autonomy, ‘New China’ — why Mao went to war with India in 1962

Critical evaluation of Nehru’s strategy

Nehru had adopted a pragmatic strategy till 1959 to deal with China. It is wrong to say that he misread the intention of the Chinese. He was clear that competitive conflict for power with unsettled borders would lead to conflict. Given the economic constraints of a poor developing country, he chose to rely on diplomacy to bide time for creating the necessary border infrastructure and the military capability. With respect to the frontiers, he adopted the traditional forward policy to flag mark our territory using police and paramilitary. The only other option was to become a subservient ally of the US. In my view, Nehru certainly gained a decade but despite the economic constraints, his efforts to create the border infrastructure and the desired military capability lacked drive and were woefully inadequate.

By the end of 1959, flag-marking forward policy had reached its culmination. The goings-on in the frontier regions had been secretive and were not in the public domain. The border clashes and casualties led to immense Parliament and public pressure. Domestic politics made Nehru lose his nerve. He committed his biggest mistake by shunning negotiations and opting for a strategy of brinkmanship with aggressive forward movement of troops in penny packets despite China offering a status quo settlement. The premise was that China will not escalate the situation to start a war.

All his subsequent actions were panic-driven and tactical, bereft of strategic thought. Due to reckless brinkmanship to call the perceived Chinese bluff, India blundered into a war over unfavourable terrain with an ill-prepared Army. Due to psychological collapse of the political and military leadership, we could not even salvage the consolation of a good fight. The rout was humiliating and absolute. Due to a quirk of fate, despite an abject defeat, the frontiers got converted to borders albeit with the loss of Aksai Chin. Onset of winter and assuming that India had been punished enough, the Chinese withdrew across the McMahon Line in the east and the 1959 Claim Line in Ladakh. Nathu La 1967 and Sumdorong Chu confrontations with a resurrected Indian Army further cemented the borders.

Also read: Walong: How Army held off a massive Chinese onslaught & launched only counterattack of 1962 war

Striking parallels of Modi’s China strategy

So long as the status quo on the borders was not disturbed, peace prevailed. Five agreements were signed to manage the borders. Economic cooperation increased by leaps and bounds. The period between 1987 and 2007 was a reversion to the Nehruvian policy followed till 1959. However, as the economic and military capabilities of China grew rapidly and India’s grew moderately, civilisation instincts came to the fore. India’s emergence as nuclear power and its alliance with the US was seen as a challenge by China. Development of border infrastructure, which began lethargically in 2007, was given greater impetus by PM Modi with effect from 2014. Friction on the borders increased with the 2013 and 2014 incidents.

The RSS and BJP are ideologically committed to recovering our lost territories. Modi, like Nehru, wanted time to economically and militarily catch up with China. Diplomacy and economic cooperation reached dizzy heights. Modi has met and engaged with Xi Jinping more times in six years till May 2020 than all such engagements from 1949 to 2014. Simultaneously, India had also become more assertive on the borders with forward movement of Indo-Tibet Border Police and aggressive development of roads in sensitive areas of Depsang Plains, Patrolling Points 15 and 17 A, north of Pangong Tso, and Demchok, which as per Chinese perception are across the 1959 Claim Line. Doklam was a warning bell just as Longju and Kongka La incidents were in 1959. Modi countered it with personality driven diplomacy of two informal summits.

National mood was upbeat. The BJP government sold the idea that Pakistan had been reduced to a nuisance and China had been contained. But Modi forgot that power flows from the barrel of the gun. China surged way ahead of India in both instruments of hard power—economy and military capability. Like Nehru, due to economic compulsions and, surprisingly, lack of drive, Modi could not transform the military to match China.

When China precipitated the crisis in Eastern Ladakh, Modi was in the same situation as Nehru was on the eve of the war in 1962. It is to his credit that unlike Nehru, he did not recklessly blunder into a war from a position of terrain and military disadvantage. Barring being surprised and crude obfuscation to mislead the public, I cannot fault him for his handling of the crisis. Loss of control of 1,000 square km is a small price to pay for buying time to economically and militarily catch up with China. Nuclear weapons and the uncertain outcome of limited war ensure that the China-India border cannot be substantially redrawn. The challenge is to demarcate and delineate it on favourable terms. This is what Nehru could do in 1959 and Modi can do now.

Given the experience of Modi since 2014, I have no doubt that history will judge Nehru kindly. By 2049, when China hopes to become a great power, India’s national aim should be to become the principal challenger.

Lt Gen H S Panag PVSM, AVSM (R), served in the Indian Army for 40 years. He was GOC in C Northern Command and Central Command. Post-retirement, he was Member of Armed Forces Tribunal. He tweets @rwac48. Views are personal.

This article is part of the Remembering 1962 series on the India-China war. You can read all the articles here.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)