There was no longer any way to put it off; in July 1940, the army-dominated government of Imperial Japan had come to a strategic fork in the road. Angered by its ongoing aggression in China, the western powers (the US, UK, and the Netherlands) had enacted a full oil embargo to stop Tokyo’s militarism in its tracks. Despite its stockpiles, the Japanese high command knew this was a potentially game-changing economic blow as, together, the three countries supplied Tokyo with an overwhelming 90 percent of its energy needs. Unless Japan engaged in the most humiliating about face, ending its adventurism in China (on which its government had staked everything), Tokyo’s economy would soon literally grind to a halt. A decisive strategic choice had to be made, and quickly.

For a militaristic Tokyo, existentially endangered by the looming US oil embargo, the choices were: To double down on fighting in China, seizing the whole of the country (and controlling its resources); strike the resource-rich (and thinly defended) Dutch East Indies (today’s Indonesia); or obliterate the powerful American fleet in Pearl Harbour, destroying American influence in the Pacific as a whole. As the world knows, the Japanese disastrously opted for Option 3, leading directly to their own ruin.

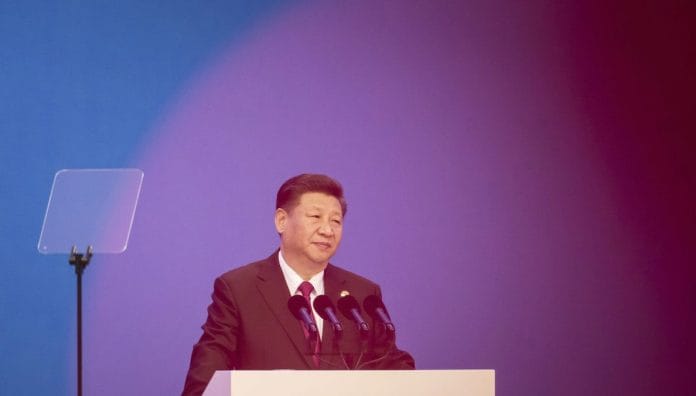

Much as was true for Imperial Japan in the early 1940s, the China of today has reached a similar strategic fork in the road. Xi Jinping’s Chinese Communist Party finds itself under pressure, though its predicament is caused by nothing so much as the immovable forces of geography.

For it is geography that is hemming in Beijing’s efforts to dominate the Indo-Pacific. China is stymied by being bottled up by ‘the first island chain’ that rings it. Running from Taiwan through Japan and the Philippines before ending at the Strait of Malacca in the south (around Indonesia, Singapore, and Malaysia), China finds its commercial and strategic prospects under perpetual peril to blockade from the US and Japan to the north at the Strait of Taiwan, and from the US, Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore, and India to the south.

Breaking out of its naval and commercial geostrategic imprisonment at the hands of an organically growing US-led anti-Chinese coalition comprising the key states of the first island chain is the key strategic battleground of the incipient Sino-American Cold War. It is simply impossible for Beijing to become master of East Asia, let along the Indo-Pacific and then emerge as the world’s dominant superpower, without it doing so.

As was true for Imperial Japan, Xi’s China has three broad strategic options: The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) overland route; the southern route (Strait of Malacca); the northern route (Strait of Taiwan). Xi’s coming strategic choice is as momentous as it has been understudied. Here are how the three strategic gambits look from his eyes.

Also read: National security or China Inc? Xi is cracking down on global dreams of homegrown companies

The BRI overland route

The formidable (at least on paper) BRI is the geo-economic cornerstone of Xi’s tenure in office. Putting its vast surplus capital and newfound macro-economic power to geo-economic use, the BRI amounts to a vast Chinese-funded network of railways, energy pipelines, highways, and ports.

An overwhelming 139 countries have endorsed the BRI in one fashion or another (including western, pro-American countries like Italy, Portugal, and New Zealand). Making a great success of the Silk Road Overland Route would enable Xi to side-step war with the US and its allies (unlike the other two strategic options) by geo-economically linking the dominant Eurasia landmass together under Chinese tutelage. By its overland geographic nature, the BRI option would make the first island chain (and the still pre-eminent US navy) irrelevant.

Over decades, a successful, embedded BRI could create an extensive spider web of economic dependence on China in much of Asia, the Middle East, and even Europe. As many of the Eurasian partners of BRI are desperately in need of updated infrastructure, Beijing is dangling an enticing and necessary carrot before their eyes.

The problem with this option is that BRI has amounted to far less than these impressive headlines. First, there have been predictable problems with corruption involving BRI projects; for example, in Malaysia over US $7.5 billion in government money for BRI projects simply disappeared.

Second, the BRI has become synonymous with ‘debt trap diplomacy,’ as a failure of the recipient states to pay back their infrastructure loans have led to China confiscating their property, put up as collateral. The most egregious case of this was the handing over by an impoverished Sri Lanka of its main Hambantota port to Beijing for 99 years, in lieu of making good on its loan payments.

Third, rather than stimulating local economies along the BRI route, all too often, Chinese workers are called in to facilitate the infrastructure projects, sidestepping local unions and labour laws and embittering local populations in general. As such, the BRI is increasingly seen as a programme to keep Chinese workers employed, rather than helping local communities along the route.

Fourth, the political risk for China in dealing with many differing governments across thousands of miles is huge. This gigantic political risk also holds true for developed countries such as Italy, which—with a change of government from the pro-China Five Star Movement to the more traditional, pro-Atlanticist government of Mario Draghi—has gone from keen to skeptical about the BRI.

All these factors have taken some of the shine off of Xi’s flagship geo-economic policy venture. Chinese overseas investments through the BRI amounted to US $47 billion in 2020, a steep fall of 54 percent from the year before. The BRI strategic option will remain viable for Xi — especially if China relatively booms in the post-pandemic world as the west fades — but, given these many and obvious problems, it will remain a backup plan.

Also read: India alone on Afghan chessboard as US, Russia pick Pakistan. Here’s what Delhi can do

The southern route (Strait of Malacca)

Only 2.7 kilometres wide at it most narrow, the Strait of Malacca is a natural bottleneck, ideal for shutting off the Pacific (via the South China Sea) from the Indian Ocean (via the Andaman Sea). The Strait is directly controlled by Singapore, which is a longstanding US ally; the predominant American Seventh Fleet can easily be mobilised to shut off the bottleneck at present.

While China has been militarising islands in the South China Sea over the past decade, the Strait and its Indian Ocean side remains firmly under US/Indian control, with the Indian Nicobar Island chain being a key to this geo-strategic advantage. The Chinese have given some thought to trying to bypass the Strait, through the construction of the Kra Canal in Thailand, but this US ally’s wariness (and the fact that anti-Chinese naval forces could be redeployed to bottle up the canal entrance) makes this a non-starter.

While Beijing would dearly love to break out of the Malaccan stranglehold, and theoretically it is possible, in reality the southern route amounts to the least likely of the three options for Xi. Malacca is simply too far away from China’s strategic locus of power, logistically making this option fraught with peril. In addition, it would involve Beijing possibly having to militarily take on a host of pro-American allies beyond the feared Seventh Fleet, including Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, as well as great power India. Both too far away and too difficult, the southern route amounts to a non-starter of a strategic option for China.

Also read: India should presume that China negotiates to deceive, says former foreign secretary Vijay Gokhale

The northern route (Strait of Taiwan)

All this leaves the northern route, geo-strategically opening the corked bottle via the Strait of Taiwan. Only 160 kilometres wide at its narrowest point, the Strait separates China proper from the island democracy of Taiwan; as such, the logistical problems bedeviling the southern route are simply not applicable here.

Also, in its strategic favour from China’s point of view, there are far fewer allies likely to rush to America’s defence in militarily supporting the over-matched Taiwanese. While Japan’s Deputy Prime Minister, Taro Aso has just made it clear that Tokyo would regard an attack on Taiwan by China as ‘an existential crisis,’ and come to America’s aid, in practice while this would amount to important refueling and logistics support, there would be far less Japanese support in terms of joining America in the actual desperate fighting.

Beyond doing away with the geo-strategic imprisonment of China by the first island chain, allowing the Chinese navy to at last break out into the open seas, the northern route also offers Beijing a number of other highly significant strategic enticements. As the world’s leader in the production of semiconductor chips, China conquering Taiwan would allow Beijing to corner the market regarding this vital economic input.

Perhaps, most of all, the demonstration effect of America losing a pitched battle with China (or even, worse, scurrying away from its commitments to Taiwan by choosing to leave the island to its fate) would have an absolutely momentous psychological effect across the Indo-Pacific. A legion of American allies in Asia would all be asking the same telling question: If the US is unwilling to come to the defence of a longstanding democratic ally like Taiwan, what is to stop it from failing to do so again?

In such a case, it is not too much to say that with American credibility in tatters, the US’ carefully constructed Indo-Pacific alliance structure would itself come entirely unglued, as India, Japan, Australia, Vietnam, and the other ASEAN countries would draw the obvious conclusions and try to make terms with a newly-dominant China.

For all these reasons — far easier logistics due to geographical proximity, fewer American allies to contend with, China’s domestic nationalist touchstone, Taiwan’s vital semiconductor industry and the pivotal demonstration effect — the northern route is the logical strategic choice from Xi Jinping’s point of view as to how to break out of his first island chain imprisonment.

Also read: Defence ministry extends emergency powers to armed forces as India-China stand-off continues

The locus of the Sino-American Cold War

If Taiwan is now ground zero in the new Sino-American Cold War, recent events make it increasingly likely that the conflict will not be settled peacefully. The harsh Chinese crackdown in Hong Kong makes an obvious lie out of China’s pious offer of ‘One Country, Two systems,’ to Taipei in return for its acquiescence in reunification. Indeed, a 2020 Taiwan National Security Survey poll found that only a miniscule one percent of Taiwanese support immediate reunification with China. If reunification is to come, it will be at the barrel of a gun.

In the next few years, look for Beijing to hope their general ‘salami slicing’ tactics work over Taiwan, in an effort to both get what they want and to avoid the cataclysm of a general conflict with the US. Increasing overflights, naval incursions, cyberattacks, and diplomatic pressure will all be ratcheted up. As President Kennedy found to be true in the US-Soviet Cold War over Berlin, America’s enemy will look for signs of its half-heartedness, in an effort to divide the US from its allies.

If, in the next five to six years, this schism fails to happen, we will have reached the moment of truth — either Beijing will accept its strategic imprisonment within the first island chain, and radically alter its geo-strategy in becoming a more status quo power, or Xi will continue on his present course and battle will be joined.

Of course, this makes for the most sober reading. However, seeing China’s options from Xi’s point of view leads us to no other conclusion. We must prepare as best we can for what is to come. The imperative of Ethical Realism is to see the world as it is, warts and all, and then strive to make it better. With regards to America, its best course is to build up its defences in the Indo-Pacific, and particularly its alliance structure, as the deterrent effect that a dominant American-led alliance can bring about in terms of Chinese strategic decision-making is the last, best thing the US can do to maintain the present world order, and peace in the world we live in.

The article first appeared on the Observer Research Foundation website.

John C. Hulsman @JohnHulsman1 is President and Managing Partner of John C. Hulsman Enterprises, a political risk consulting firm. He is also a life member of the US Council on Foreign Relations. A senior columnist for City AM, John writes for The Hill, and Arab News. Views are personal.