The shock of the electoral outcome appears to have obscured a deeper story of the return of state politics to the centre stage of national election.

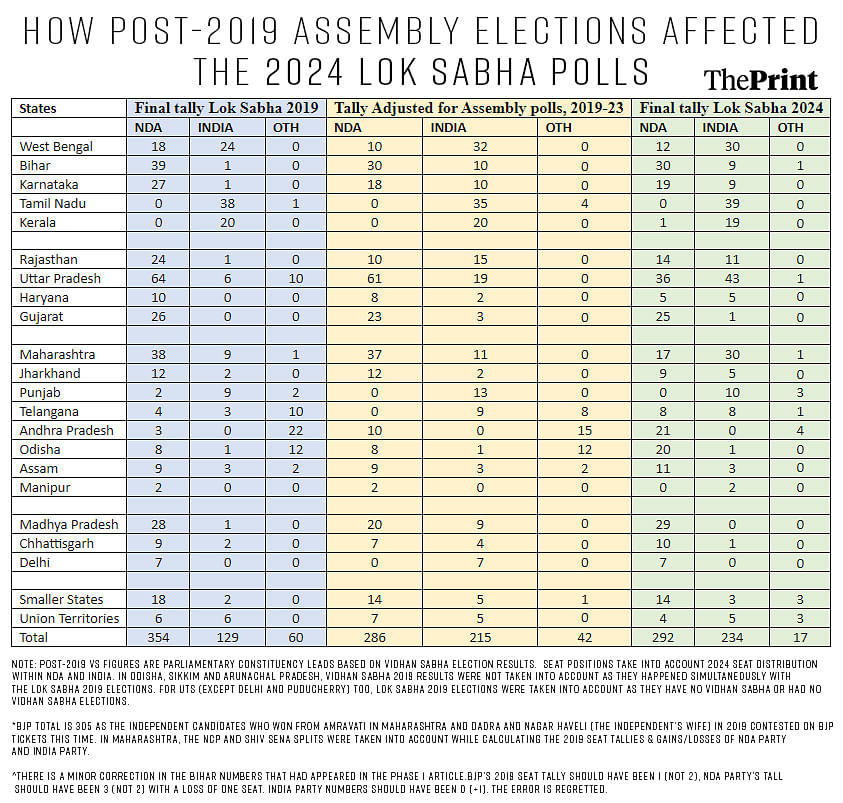

Let us begin this story with some startling figures we had presented before 4 June: NDA 286 seats, including BJP 237; INDIA alliance 215, with Congress at 89. The resemblance to the final outcome is spooky, isn’t it? Just to refresh your memory, the final tally was: NDA 292 (BJP 240), INDIA alliance 233 (Congress 99).

No, these figures were not predictions. They are simply the ‘adjusted’ tally of Lok Sabha seats based on the Assembly elections that have taken place after the 2019 general election.

Since every Parliamentary constituency is a neat cluster of a set of Assembly constituencies, all we did was recalculate the leading party (or alliance, adjusting for the current alliance) for each Lok Sabha seat, based on votes secured in the latest Assembly elections. We reported these adjusted figures in each of our seven-part series on the seven phases of elections in ThePrint.

Our point here is not that you can predict Lok Sabha elections based on the previous Assembly election outcomes. Hitting the bull’s eye this time is of course a coincidence. This resemblance draws our attention to something deeper: this time state-level elections provided a better starting point than the previous Lok Sabha elections for making sense of the recently concluded elections. If you were not fixated on the outcome of the 2019 Lok Sabha elections and had taken subsequent Assembly elections into account, you would have noticed that the BJP was starting the race with a deficit of about 60 seats, a fact overlooked by the entire gamut of election reporting and analysis.

Let us now look at the state-wise patterns reported in the table below to see how this analysis could have helped us understand the nature of the contest and anticipate the broad outlines of the outcome.

Let us pick a state, say West Bengal. The BJP won 18 seats in the 2019 Lok Sabha election. But by looking at the votes secured in the Assembly elections, we could anticipate that the BJP was in the lead in just 10 Lok Sabha seats. The BJP’s final performance of 12 seats would not have surprised us. Similarly, a study of vote shares in the Rajasthan Assembly results of 2023 would have prepared us for the 11 seats that the Congress and its allies won in this election. The same holds for Bihar, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu. In Uttar Pradesh, Haryana and Gujarat, the state Assembly elections help us see the direction of change, though not the extent of it.

This does not apply to all states. Andhra Pradesh and Odisha did not have Assembly elections during this period, since they had simultaneous assembly and Lok Sabha elections in 2019 and 2024. There was no early signal of the electoral earthquake that was to hit both the states . Major shifts in alliances since the latest Assembly elections make this data less useful in states such as Maharashtra and Jharkhand. Telangana, Manipur and Punjab, which witnessed dramatic political developments after the last Assembly elections, do not follow this pattern either. But in all these states, the outcome of the recent national election is very much in consonance with the altered reality of state-level electoral trends.

The only real exceptions to this trend of the primacy of state politics are Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Delhi, Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh where the BJP continued the trend of getting a bonus—a ‘national premium’, as it were—share of votes as compared to the last Assembly elections.

Also Read: Phase 7 was designed for Modi’s undivided attention. It hasn’t worked, except in Odisha

Re-emergence of the state

This apparent statistical convergence connects this election to a bigger story of Indian politics. Nearly two decades ago, one of us (Yogendra Yadav) had written a series of articles with Professor Suhas Palshikar to argue that Indian politics in the 1990s had entered a new era, the ‘Third Electoral System’, where the state had become the principal arena of electoral politics at the national level.

In the 1970s and 1980s, the Indian voters voted in the state Assembly elections as if they were choosing their prime minister. In contrast, in the 1990s and early 2000s, Indian voters started voting in the national election as if they were choosing their chief minister.

All this changed with the rise of Narendra Modi in 2014 when national politics became the principal consideration for voting in the national elections and in some, though not all, state Assembly elections.

The recently concluded Lok Sabha election marks another point of inflexion. State politics has not become the principal arena, but has certainly become a relevant context for the way voters make a choice in the national elections.

It follows that more voters have paid attention to the context of state politics than those who did so in 2019. This is confirmed by the post-poll survey of the Lokniti-CSDS which asked the voters the following question: “In deciding who to vote for, which government matters more to you?” In response, 23 per cent said the central government, 21 per cent mentioned state government, while 41 per cent said they considered both central as well as the state government. Compare this to the responses to the same question in 2019: 28 per cent named central government, while only 17 per cent named the state government.

This election has started a discussion on the partial reversal of the democratic slide-back in India. This recovery is partly due to the voters’ disenchantment with the BJP style of politics. But a good deal of this democratic rebalancing is due to the return to normal politics, of every day livelihood issues and the local context of elections. The retreat from the heights of national and nationalist anxiety and the return of state politics could well be the major force driving the democratic rebalancing that this election has achieved.

Yogendra Yadav is National Convener of the Bharat Jodo Abhiyan. He tweets @_YogendraYadav. Rahul Shastri is a researcher. Shreyas Sardesai is a survey researcher associated with the Bharat Jodo Abhiyan. Views are personal.

The authors would like to thank Prof. Suhas Palshikar for sharing his insights and data.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)