Do party workers matter in shaping election outcomes? With the 2024 Lok Sabha elections approaching, the incumbent BJP has released its first list of 195 candidates, while other major parties like the Congress have also started unveiling their candidates. Amid this high-stakes campaigning focused on star candidates and party leaders, the grassroots party workers—the nerve centre driving voter outreach—often get overshadowed.

But are these workers, with their direct and prolonged voter engagement, a deciding factor? More importantly, are workers of certain parties more actively involved than others? And can this varying engagement level impact the electoral fortunes of the candidates they campaign for?

To investigate, we look at a post-poll survey from the 2023 Madhya Pradesh assembly elections, where the BJP and Congress were dominant competitors. This survey was specifically designed to understand the role of party workers in election campaigns. We interviewed 206 respondents across 46 carefully sampled Vidhan Sabha constituencies representing all regions. This included 42 elected representatives (MPs, MLAs, and Mayors), 71 district-level officeholders, and 93 ground-level activists.

The respondents revealed fascinating differences in the average responses from BJP and Congress workers on three aspects: 1) Time dedicated to campaigning; 2) Whether leadership sought their opinions; and 3) Satisfaction with the candidates fielded.

The survey offers insights into the intra- and inter-party organisational dynamics of these two parties.

Also read: Political parties battle each other in Indian slums by using rumours and violence

Three metrics

Both the BJP and Congress state headquarters dedicate considerable efforts to express gratitude to their workers and activists. However, the survey results show that the similarities end there.

While there was not much difference between the average daily hours put in by workers during the peak of the campaign (BJP’s 10.1 hours vs Congress’ 9.3 hours), the BJP had started mobilising much earlier through initiatives like ‘Booth Vistaar’ strategy. A BJP district president explained how the process began more than a year before the elections and involved distributing responsibilities down to every page of the voter list. In sharp contrast, many Congress activists revealed that they believed the party got “too confident” in the run-up to the elections.

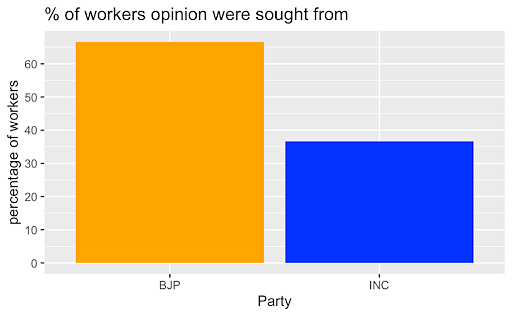

The disparity becomes starker when asked if their opinions regarding the campaign were sought and heard by the party leadership. Figure 1 shows the stark difference: Two out of every three BJP workers said their recommendations to improve the campaign and make it more relatable to the masses were actively sought. For Congress, the proportion drops to just one in three. A former Congress district vice-president said he was completely sidelined despite holding an official position, adding it explains the frustration of other party activists.

Fig 1: Is the opinion of party workers sought by the leaders?

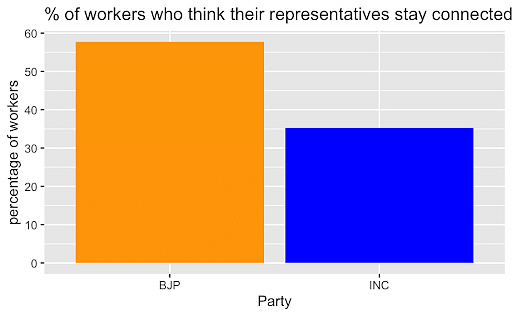

The BJP scores better in the third metric as well. Post-election, BJP workers reported far-higher satisfaction with how well elected representatives remained connected with them. There was about a 22 percentage point gap (Figure 2). This becomes especially important considering how political parties in India are increasingly replacing incumbents and bringing new candidates to overcome local-level anti-incumbency sentiments. For example, the BJP did not re-nominate five of its seven MPs in Delhi. There is a cost to replacing candidates, especially incumbents. If workers on the ground do not feel connected to their candidates and party leadership, there is always a fear of rebellion at worst, demotivated campaigners on the ground at best, increasing the likelihood of the candidate losing the election.

Fig 2: Do elected representatives stay connected with party workers?

An average BJP worker thus campaigned longer hours, felt more included in decision-making, and remained upbeat about elected leadership’s responsiveness. While Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s popularity, the BJP’s ideological appeal, the government’s new welfarism, and its command over financial and communication technology resources, among others, get lauded for putting the party in electorally dominant positions, it would be naive to not acknowledge the role of its dedicated volunteers on the ground.

Also read: Think tanks acting as war rooms. This is what Indian political parties are building for 2024

A key lesson

We agree that these findings are not completely irrefutable—especially when it comes to self-reported dedication toward the party. But that is not the main concern here; the real question is: Why are Congress workers, even if self-reported, less enthusiastic in retelling their contributions to the party? If party workers are indeed aggrandising in their account of just how much they feel close to the party, why is it that only BJP workers systematically do so? Why are Congress workers modest even in reporting something that is anyway assumed to be exaggerated?

The reason party organisation and workers’ management are an important determinant is simple—if your own party activist does not feel included and committed, how do you expect them to convince a presumably bipartisan voter? Congress leaders claim that their party is not cadre-based and perhaps for good reasons.

As the election furore focuses on star campaigners, it is important to understand what motivates people to become party workers. Why do some parties effectively mobilise this ground force while others fail? Do incentive structures for these workers vary across parties?

The data offers lessons for both political scholars and parties—never take workers for granted. Beyond shaping campaigns on the ground, their enthusiasm could tilt election outcomes. They definitely make the final difference in closely contested elections.

Rahul Verma is Fellow, Centre for Policy Research (CPR), New Delhi. He tweets @rahul_tverma.

Pawas Pratikshit is at Sciences Po, Paris. The survey of party workers was conducted in-person by Pawas Pratikshit as part of his Masters’ Dissertation. He tweets @PawasPratikshit.

Views are personal.