Plato and Aristotle had diametrically opposite views on the sustainability of democracy. Plato, in Book 8 of The Republic, wrote that democracy was fundamentally unstable. He said that liberty given to people made room for the rise of demagogues among them. Demagogic competition for power inevitably leads to tyranny.

Aristotle, on the other hand, in Politics, Book 5, Chapter 5, believed people craved an equal distribution of privileges and goods in society — something that only a democracy could provide. The desire for a more equal society would make people reject demagogues, making democracy the most resilient form of government. Both of them agreed though that democracy was inherently vulnerable to capture by demagogues.

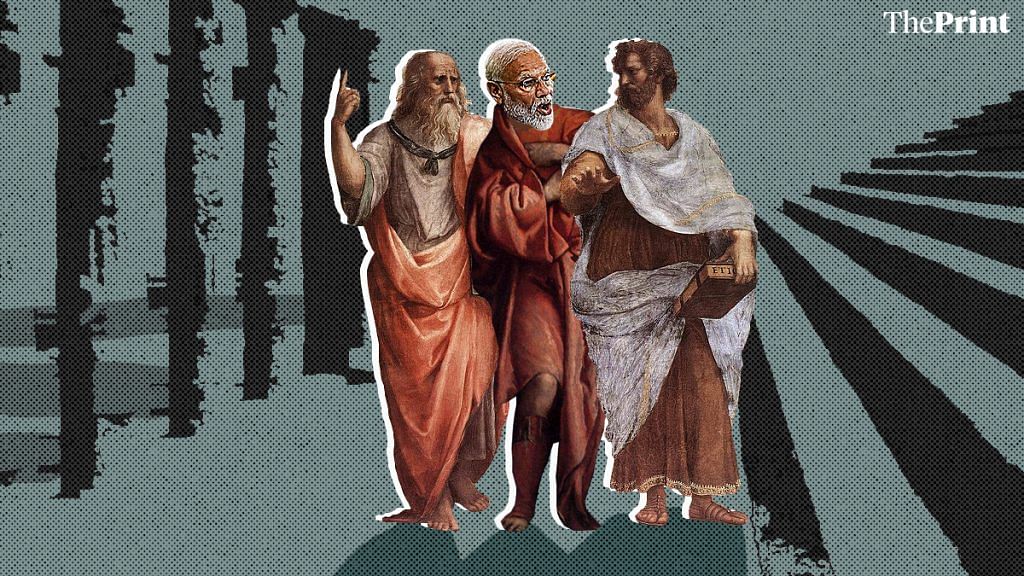

With Indian democracy poised at a critical juncture, as Narendra Modi begins his second term in office, it is worth examining if the desire for an egalitarian society, as Aristotle postulated, will manage to keep demagogues in check, or if demagoguery will eventually lead to tyranny, as Plato thought was inevitable.

Kant’s reasoned will

At the heart of democracy lies the Kantian notion of a reasoned will. Democracy decides on an issue through debate and discussion among members or their representatives, in an assembly designed for the purpose, where free speech is guaranteed. Reasoned will is not just an aggregate of ideas and thoughts of the people. Nor is it merely the will of the majority. As Aristotle explained, reasoned will is something that emerges as a consensus out of an honest debate among people in a deliberative assembly that guarantees free speech. A majority, without due deliberation, is not the reasoned will of the people. Without a robust mechanism for determining reasoned will, democracy cannot exist.

Demagoguery, on the other hand, is a rhetorical device to bypass the reasoned will of the people, by appealing directly to the emotions of a section of the population, often the majority.

Let us say a community needs to decide where to locate a school. Reasoned will would require a rational consideration of suitability of site, facilities, terrain, distance, etc. A broad compromise between various interest groups on various parameters would be necessary to finalise the location. That would be reasoned will. The decision would then be put to the majority test before its adoption.

Also read: In the Rahul vs Modi battle, why Shobhaa De would choose duffer over demagogue

On the other hand, let us say, all the various interest groups can also be divided into two broad communities on the basis of religion, colour, or social status. A demagogue would appeal to the same interest groups, but on the basis of, say, religion, to demand that the school’s location should be decided after finding out which religious group in that locality commands a majority. He would cite narratives to claim that his favoured community was denied such an opportunity in the past, or how the religion of the majority should be the foundation of the country’s education system. Any emotive appeal will do.

This appeal to emotions of one (majority) group while pushing away the other group in order to bypass the reasoned will of the people is demagoguery. The key here is that while reasoned will requires applying reason to solve the problem, demagoguery seeks to bypass reasoning altogether, by turning the problem into an unrelated emotive issue. Demagoguery is democracy’s Kryptonite.

Emotions are often more powerful than reason in rousing people into action because the demagogue deliberately chooses issues that are intrinsically linked to a group’s identities with a history of fault lines separating them.

We are hardwired to hate instantly. Trust and love take time to work out. This makes hate a very powerful emotive tool in the hands of a demagogue. Given that communities have historically faced several ups and downs, fabricating real or imagined grievances against one or the other group, whether in the past or present, is not very difficult. Such issues exist at all times and only need to be invoked. In normal circumstances, these are usually ignored in favour of reasoned will. But in times of stress, conflict, or sudden upheavals, these issues come to the fore with demagogues waiting to exploit them.

Plato’s problematic solution

If demagoguery is an ever-present danger to democracy, how do we fight demagoguery?

The question baffled Plato, who thought demagoguery would inevitably win, because every demagogue would be followed by a more skilful and more virulent demagogue, until one simply took to tyrannical rule by ending even the farce that the democracy eventually becomes in the absence of reasoned will.

Plato’s solution to the problem was itself problematic. He favoured a dictatorship by a committee of guardian-philosophers who themselves would be all but communists. Plato’s solution was deeply flawed. But it is worth noting here that the greatest mind in antiquity was baffled by the question of how democracy can be protected against demagoguery. That in itself tells us how difficult the problem is.

Also read: Putin’s wrong on liberalism, but so are liberals themselves

Aristotle’s appeal, with a caveat

What was Aristotle’s solution? Aristotle believed it would always be possible to build a majority around the concept of equality. Equality here is not the neoliberal equality of wealth or income as measured by a Gini coefficient, but equality of status, privilege, distribution of goods, and opportunity in a given society.

If you envisage a society as some sort of a stratified pyramid, with plebeians at the broad base and elites at the narrowing top, you can readily see that in terms of numbers — an overwhelming majority of people in the natural state would be in favour of equality, because the lower you are in the pyramid, the greater your number, and the more your craving for equality.

So, Aristotle’s solution was an appeal to equality, on the basis of reason and/or emotion, since both were aligned to achieve the aim of defeating demagoguery. Note that every religion since antiquity has been built around the appeal to equality. Hinduism itself has often branched out into different streams from its main caste roots based on disagreements over equality or the lack of it.

So, the astute Aristotle was not very far off the mark. On the other hand, without expressly saying so, Aristotle also concedes that demagoguery can only be fought by demagoguery, albeit one that is aimed at restoring equality. Note that this is not the Gini coefficient-based kind of neoliberal equality, but the real thing.

Majority’s role, ultimately

From a commonsensical point of view, the inevitability of Aristotle’s preferred solution is obvious. If a demagogue seeks to divide the society into two communities on the basis of religion, what do those opposed to the idea do to fight the demagogue? Obviously, the first thing is to point out that all are equal in a society. It helps if people in favour of equality are evenly spread in both communities and are willing to campaign against the demagogue and those siding with the leader, with a common approach. The other option is to carry on practising equality no matter what the demagogue says. If Aristotle’s pyramid holds true, the yearning for equality will inevitably prevail as the demagogic influence wanes with time.

Also read: Rahul Gandhi is as polarising as Modi but Indian liberals won’t use that word for him

However, application of Aristotle’s remedy is complicated when [a] the size of numbers massed on either side of a fault line are highly skewed; or [b] the demagogues themselves start competing with each other to gain the favour of the majority. In India’s case, Muslims are just 15 per cent of the population, while Hindus are 80 per cent. That is a highly skewed sample. A demagogue competing with another demagogue may be a foreboding future that still lies ahead of us. But getting rid of demagoguery depends on the reasoned will of the majority, and not the minority. It is the majority’s yearning for equality that will help us defeat demagoguery.

What are the practical consequences of the Aristotelian view about contesting demagoguery that derails democracy? The short answer is reinstating reasoned will of the people as the key to making democratic decisions. This is done by appealing to the yearning for equality of all citizens, whether they belong to the minority or the dominant class. Second, the dominant class must lead the movement for restoring equality for all, and not just of its own members. And lastly, the movement for equality must find a charismatic leader capable of standing up to any demagogue within the polity.

Equality, liberty, and fraternity are the only viable answers to the threat of demagoguery.

Sonali Ranade tweets @sonaliranade. Sheilja Sharma tweets @ArguingIndian. Views are personal.