What if someone told you that the cropped area of an entire state like Bihar would be used to produce crops for producing fuel? Our calculations show that this is what India will need to achieve its ambitious E20 plan of blending petrol with ethanol by 2025-26. Of course, the crops have by-and co-products and therefore the entire land won’t technically be exclusively used for crops-for-fuel.

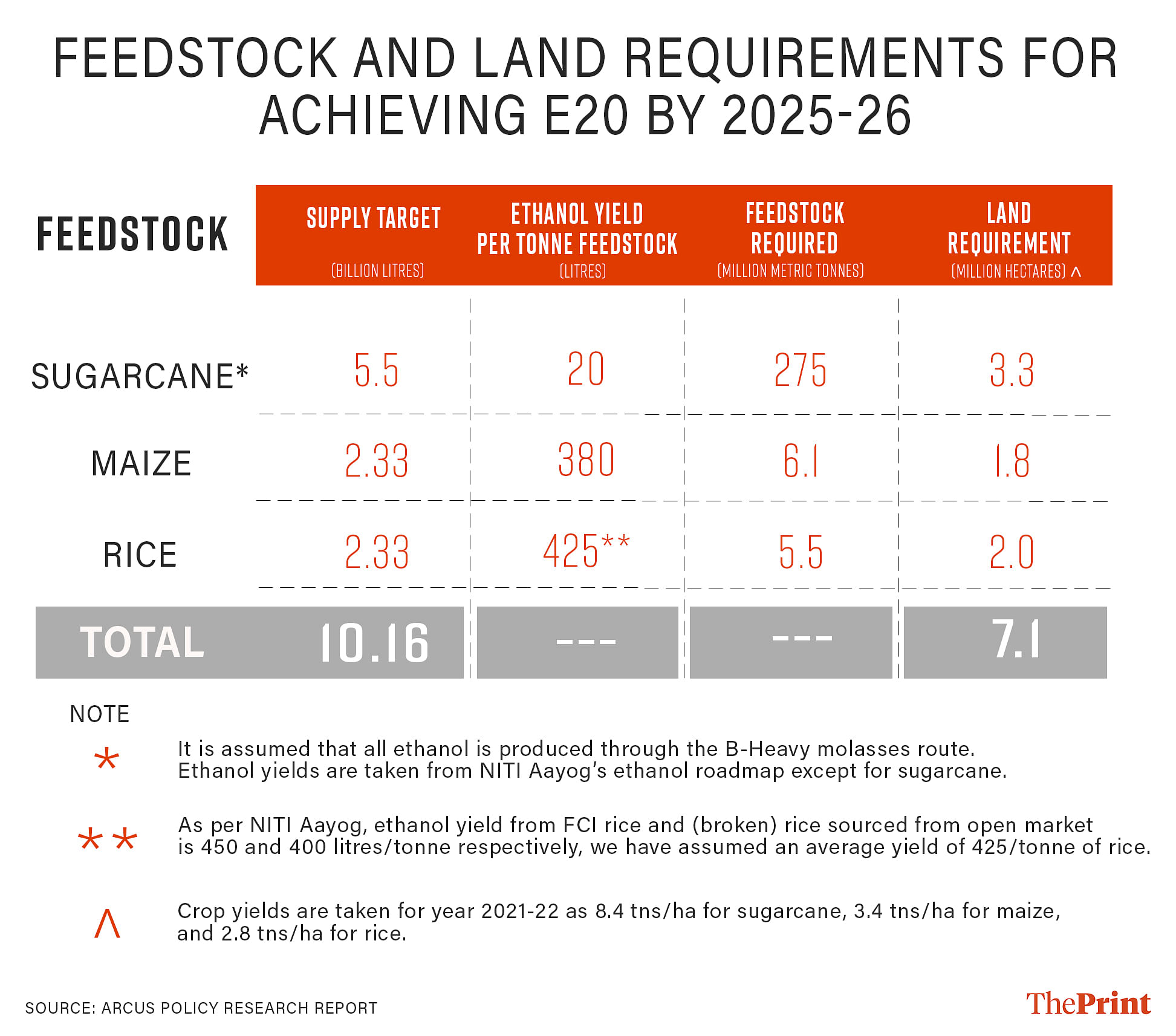

As per our estimates, in order to produce 10.16 billion litres of ethanol (requirement for E20 as estimated by NITI Aayog) from three crops – sugarcane, maize, and rice – India would need about 275 million metric tonnes (MMTs) of sugarcane, 6.1 MMTs of maize, and about 5.5 MMTs of rice. Considering today’s average crop yield levels, this implies a requirement of about 7.1 million hectares of crop area. We believe that the ambitious targets of E20 require a rethink. India needs a medium- to long-term roadmap.

What is E20?

We know that India depends on imported fuel to meet its energy needs. In 2021-22, 86 percent of consumed fuel was imported. With such high import dependence, the country emerges as highly vulnerable to global events like the Russia-Ukraine war or decisions of OPEC countries, among others. To reduce this dependence, one of the globally accepted ways is to blend petrol with ethanol. By such blending, overall fuel demand falls while the efficiency of the vehicles using the blended-fuel does not suffer much. Ethanol can be produced directly from agricultural crops or their waste. The resultant reduced demand for fuel could save India about $4 billion annually. It could be a win-win situation on all accounts.

E20 refers to a blended fuel with 80 percent petrol and 20 percent ethanol. Currently, India’s blending rate is 11.75 percent. The central government would prefer moving towards its E20 target aggressively, hoping to achieve it in the next two years, by 2025-26.

Also read: Delhi must push Russia to open Black Sea ports. Africa won’t get Indian rice this year

Annual ethanol requirement

The NITI Aayog’s roadmap for ethanol blending to achieve E20 by 2025-26 estimates an annual requirement of 10.16 billion litres of ethanol. It needs to be remembered that industries like cosmetics, alcohol, and pharma also have continued ethanol requirements. As per NITI, these additional demands would be about 3.35 billion litres in 2025-26. So, in total, the country would require about 13.5 billion litres of ethanol annually.

To meet the E20 mandate, NITI outlines the feedstock requirements. About 55 percent of the 10.16 billion litres would come from the sugar industry. Food grains, including surplus rice with the Food Corporation of India (FCI), rice from the open market, maize, and other damaged crops would supply the remaining 45 per cent.

If current crop yields sustain, ethanol-yields of feedstock are maintained, and ethanol production from grains is equally contributed by rice and maize, then, as per our calculations (Table 1), the country would need about 5.5 MMTs of rice, about 6.1 MMTs of maize, and 275 MMTs of cane (ethanol is a by-product of sucrose processing and therefore this cane requirement would also produce sugar and other useful co-products). To produce these, the cropped area requirement would be about 7.1 million hectares.

As per the Directorate of Economics and Statistics under the Ministry of Agriculture, Bihar’s gross cropped area (GCA) in 2019-20 was about 7.2 million hectares and that of Andhra Pradesh was about 7.3 million hectares. Therefore, to understand it in simple terms, it can be said that an area as large as Bihar’s GCA may have to be dedicated to produce crops for fuel if E20 is to be achieved by 2025-26.

Also read: Soybean should become the next egg. Needs NECC-type campaign, support

Can the required feedstock be made available?

As part of our research, we used historical data on crop yields and acreages, and simulated for both supply and demand situations of the three crops. We built scenarios for impacts of climate change, growth in demand of alternate industries, and for technological advancements in crop yields.

The results show three important things:

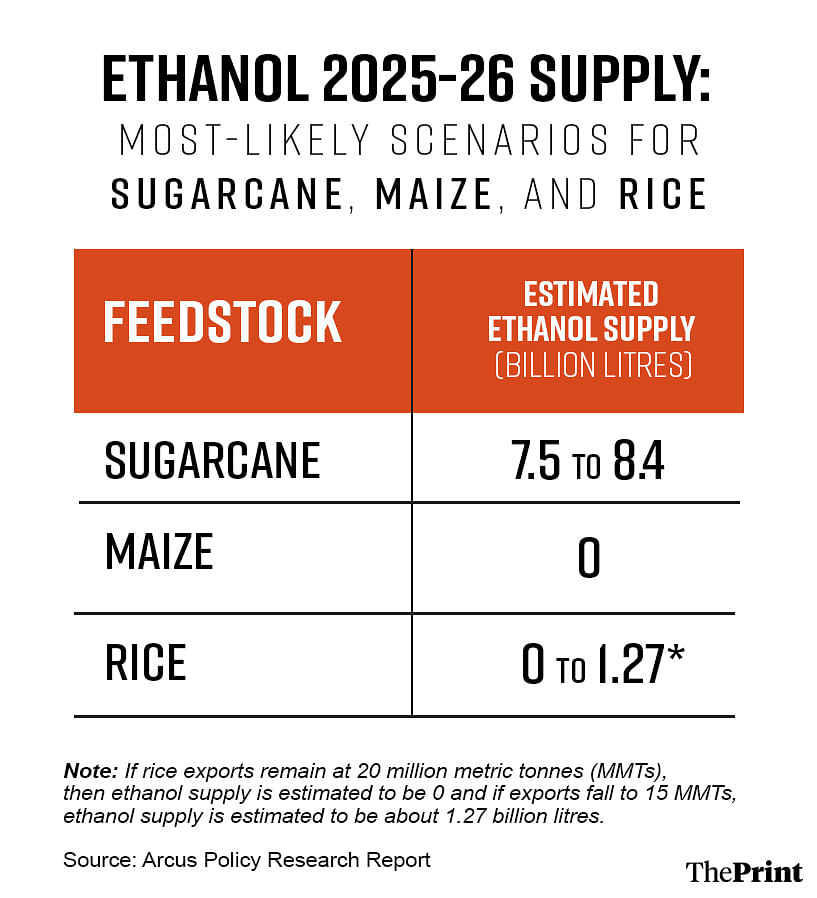

- Sugarcane is going to be the central and most reliable source of ethanol supply in the country. But will the current surpluses in the crop continue into the future too? Last year, the Indian Sugar Mills Association (ISMA) revised its cane production estimate downwards thrice;

- If the historical growth of both food, feed and starch industry continues, then under the studied scenarios, there emerges no surplus maize that can be made available for producing ethanol in the country; and

- In the case of rice, there emerges to be a trade-off between exports and rice for ethanol. The former will have to be reduced to make space for oil marketing companies (OMCs) seeking rice for ethanol.

Under all scenarios, we assume that the crops will first be utilised to meet the country’s food demand. Any excesses are shared in Table 2.

Overall, against the requirement of 10.16 billion litres, we estimate that India will be able to supply anywhere between 7.5 to 9.6 billion litres of ethanol in 2025-26. The ability to supply the additional ethanol requirement of 3.35 billion litres remains another puzzle. However, unlike ethanol-for-fuel, ethanol for other needs are open to be supported via imports.

Also read: Bananas are India’s horticulture success story. Time to up the game in international markets

What now?

In 2018, when the E20 roadmap was being designed, the country appeared to be in a ‘surplus’ situation, at least in all the three crops: sugarcane, maize, and rice. A lot has changed since then.

Sugar production has fallen in 2022-23, its exports are now restricted and given a choice, sugar mills would rather export sugar to benefit from high global prices.

Maize is stretched on all sides: from increasing demand in the starch industry to poultry feed industry that is growing at double-digits, maize is struggling to find ways to the OMCs for producing ethanol.

Rice is an interesting case. Due to two consecutive years of erratic monsoons (2022 and 2023), rice production appears squeezed, so much so that the government has banned the export of non-basmati raw rice. Media reports suggest that FCI too has had to stop the sale of rice for ethanol production.

There is no doubt that the country is making commendable efforts to reduce its fuel import dependency through its E20 mission. However, the mandate to achieve this by 2025-26 appears aggressive, not to mention the concerns about crop and land resources competing for fuel and food crops. A careful roadmap must be drawn to ensure a steady supply of feedstock for the distilleries.

As per the latest SOFI Report, India’s population of undernourished people is still among the largest in the world. We need growing acreages in pulses, oilseeds and horticulture crops. Besides, there is no doubt that the country has to draw up its resilience plan to counter the adverse impacts of climate change. The importance of improvements in crop yields cannot be over-emphasised. From better seeds to efficient techniques of production, we need efficient crops, particularly when those crops will be used for producing fuel.

The country will do well by starting with a land-use plan. In the longer run, we should not use our existing crop land to produce crops for fuel. Instead, the country has been losing its arable land. In the 40 years between 1978-79 and 2018-19, India’s fallow land (those that have not been cultivated for more than one year but less than five years) increased by about 4.3 million hectares. Can this land be prioritised for producing crops-for-fuel?

There should not be a trade-off between achieving food and energy security in any country. As both are critical, a strategic and a cohesive roadmap is the need of the hour.

Saini is an Agricultural Economist and CEO, Arcus Policy Research and Hussain is former Agriculture Secretary, GOI. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prashant)