Last week, amid major political controversies, a tech CEO and an author of mythological fiction caused a furore about sati, the practice of widow-burning in medieval India. This worked up a storm on social media: while liberals pointed to colonial records claiming it was endemic to Indian society, the Right declared it all missionary propaganda to defame Hinduism.

The reality of sati doesn’t support either end of the political binary. The ritual was not exactly a daily occurrence, but the overwhelming weight of medieval evidence shows that it was practised by elites all over the subcontinent.

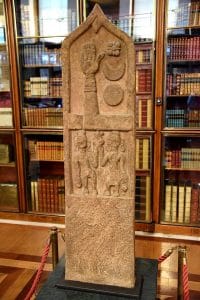

Written in stone

Scattered across a huge swathe of the Indian subcontinent—from Gujarat through Maharashtra and Karnataka, and all the way to Tamil Nadu—are stones carved with human figures, meant to memorialise the valiant dead. These memorial stones number in the thousands, and they contain quite a lot of information about medieval deaths (at least the deaths that society chose to remember).

The majority of these stones speak of the deaths of men: in squabbles between villages, cattle-raids, while fighting off bandits or wild animals. But a significant proportion are sati stones. Often in contemporary India, we are so caught up in mythology that we forget to look at the very real evidence left by medieval people.

Some sati stones are inscribed, telling us the name of the deceased woman and her motivations—at least, as regarded by her male contemporaries. We know, for example, of Dekabbe, who perished in October 1057, in a sati ritual in the highlands west of Mysuru.

Dekabbe’s husband had been executed by a Chola king for the crime of kinslaying. Hearing the news, she is said to have declared: “Can I have any mind to live, and disgrace the good name of this house which gave me [in marriage] and of he who took me [in marriage?]”

Despite repeated entreaties from her family, she held firm. On the day of her death, the carvings on her memorial stone show she was carried to the pyre in a palanquin procession, with drummers and flautists. She gifted away all her possessions, leapt into the fire from a platform, and “went to the world of the gods”.

Posthumously, Dekabbe was praised as “the famous Dekabbe who is Sri, Gauri, Sachi, Sita, Rati, and the earth-goddess”, and declared an embodiment of heroism, generosity, and piety.

This inscription is quite revealing of the general medieval view of sati. Dekabbe belonged to a family of landlords and military chieftains, as did her husband. While her family begged her not to go through with it, Dekabbe thought that living as a widow would be a “disgrace”, while committing sati would lead to her being praised, identified with goddesses.

So while she was not technically forced into sati, there was clearly considerable social pressure on wealthy widows—especially from ruling families. A scan of medieval Kannada inscriptions, collected in the Epigraphia Carnatica, reveals many such cases.

Sati wasn’t limited to the middle aristocracy, either, like Dekabbe’s family—we know that even among the Chola family, with many powerful and independent queens, a few did commit sati and were posthumously revered. An example of this is Vira-Mahadevi, a junior wife of the famous conqueror Rajendra Chola, whose brother gifted water to feed her thirsty spirit after her sati. (Annual Reports of South Indian Epigraphy, 1916, stone inscription no. 260).

A review of medieval texts, almost invariably written by male aristocrats, suggests that sati was looked upon as an act of love, piety, and glory. Take, for example, the Vikramarjuna-Vijaya of the poet Pampa, written in the 10th century CE. The Vijaya contains many scenes where virtuous wives part from their warrior husbands. These were studied by historians S Settar and MM Kalburagi in the edited volume, Memorial Stones.

One lady declares, for example, that her husband, perishing in battle, “will unite with the celestial nymphs leaving me all alone here… Nay, I shall hasten ahead and welcome him in heaven”. (Canto X, verse 45). Many memorial stones depict warriors dying and their wives committing sati in adjacent panels. For these medieval aristocrats—both male and female—the goal was to achieve valorous deaths, which improved social standing and ensured the attainment of heaven, indeed of divinity.

There is no evidence of medieval Brahmins or working class people committing sati: it seems to have been a practice of the warlike, propertied classes who had to publicly prove their honour and status. Even among them, we know that some women did manage to carve out careers as respected widows, primarily through temple patronage. But sati memorial stones confirm that many more, for various reasons, did go through with the grisly act.

It would really stretch the imagination to claim that all these cases were purely voluntary—even if male chroniclers, representing the views of orthodox society, praised them in those terms.

Also read: Sati economy is still big in Rajasthan. No pending file on Roop Kanwar in Jaipur

Why the debate?

As we understand the reality of sati, we can also examine today’s thought processes that seek to romanticise history for political ends. The Right-wing view of sati, if last week’s controversies are any indication, can be boiled down to the following. One: the Mahabharata and various other mythological texts present sati as a voluntary practice. Two: there is a supposed lack of historically attested sati incidents, especially in the medieval period. Three: colonial missionaries routinely exaggerated sati reports and “misinterpreted” texts.

The implication: women have always been treated wonderfully in Hinduism, so why “denigrate” the religion’s history, or claim that some medieval attitudes, especially about purity and honour, still feed into crimes against women?

First, the fact is that mythological texts are texts: they are not indisputable, unchangeable, objective narratives. They reflect the views of a particular stratum of society, often male, often upper caste.

British colonial authorities arbitrarily selected texts to construct an idea of what Hinduism “really” was, but this process continues to the present—the Right wing simply cherry-picks a different set of texts. No mythological narrative can prove the existence of a perfect Indian society. Myths just tell us what one section of Indian society saw as ideal at one point in time. Even so, the Mahabharata suggests that the ideal for its time was voluntary sati, or virtuous widowhood.

Second, even a cursory reading of medieval inscriptions, across most of India, will throw up examples of sati. Not from every section of society, yes, but definitely from the landed aristocracy. As a medievalist, I constantly come across confident proclamations about how medieval society “really” was, with absolutely no basis in medieval evidence. Instead, our imagination of the medieval period conjures up a past which exists only to support today’s political agendas. Medieval evidence doesn’t matter as much as modern imagination. The past was not a place of endless oppression, but it was not a utopia either. We cannot conveniently dismiss its iniquities as “propaganda”.

Third, yes, colonial missionaries did misrepresent sati as a universal Hindu practice, when in reality, it was deeply linked to ideas of landed caste pride and women’s purity. Accepting this does not automatically mean that all sati cases were lies. It is one of the few consistently attested practices seen in the Indian subcontinent, mentioned century after century by Greek, Chinese, Arab, and Portuguese travellers.

Sati stones are not exactly difficult to find, whether in museums or in shrines. Often, they depict the hand of the deceased woman, raised upright, sometimes holding a lemon.

One cannot help but wonder, looking at these carved hands, what the lives of their owners were like: the food they must have eaten, the work they did and oversaw, the clothes they must have worn, the friendships they nurtured. All cut short by the death of their husbands and the events—voluntary or not—which followed immediately after, ending their lives.

Separated from us by a thousand years, sati stones tell a story of gender relations that in some ways we have grown beyond, but that we should never seek to forget.

This article is a part of the ‘Thinking Medieval‘ series that takes a deep dive into India’s medieval culture, politics, and history.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian. He is the author of ‘Lords of Earth and Sea: A History of the Chola Empire’, and the award-winning ‘Lords of the Deccan’. He hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. He tweets @AKanisetti and is on Instagram @anirbuddha. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)

Anirudh Kanisetti misrepresents the right wing bu saying “they deny occurence of Sati” when the denial is of involuntary occassions of it. The British, who witnessed only few and far between Sati cases, painted the whole tradition as such. We should also remember poverty increased and was more prominent in the north due to colonization, and maybe forcing one into sati was more common for honour which led to funds and maintainance. Yes, there may have been forced sati in mediaeval times, but we don’t find any literary evidence of it, and until we do, we can assume that even if forced cases exist they were not happening enough to draw the attention of the people, and maybe they were not being forced into it in the south due to more prosperity.

The point is, Anirudh Kanisetti just misrepresented the right wing’s stance, added a lens of modernity (we have “grown out of sati” nah bruh that shit is romantic and even men would commit sati for their wives if they felt the rush to) to it and interjects his opinion of “sati bad inherently” to the whole debate by creating a false sense of neutrality. The false premise of this neutrality is that the right wing claimed sati never existed. Which simply is not the stance at all. His opinion completely ruins his nuance. He should do better and let readers make up their own mind instead of trying so hard to brainwash and “save” his readers 24/7.