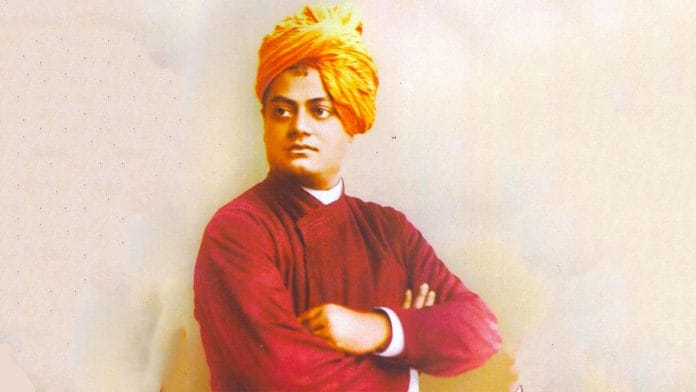

ISKCON monk Amogh Lila Das has created quite a kerfuffle by questioning whether Swami Vivekananda was really a divine persona because he ate fish. He also called Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa’s dictum ‘Jato mat, tato pat’—as many religions, so many paths—illogical. The supreme credo of our times being not to “hurt religious sentiments”, ISCKON immediately banned the monk from speaking for a month.

What would Vivekananda have said to Das’ question about a divine person eating fish? We do not have to look far because Vivekananda did comment on the attitude of the Vaishnavite sect, of which ISKCON is a very modern incarnation. “The position in which the modern Vaishnavas find themselves is rather one of difficulty. Instances are found in the Râmâyana and the Mahâbhârata of the drinking of wine and the taking of meat by Rama and Krishna, whom they worship as God. Sita Devi vows meat, rice, and a thousand jars of wine to the river goddess, Gangâ!”

One cannot help but suspect that ISKCON’s move to penalise Das has more to do with public relations than a genuine disagreement with what the monk said. After all, ISKCON’s founder and supreme preceptor Srila Prabhupada objected to Vivekananda on the same grounds. And being more colourful in his language, one of his favoured epithets for Vivekananda was ‘rascal’.

For instance, he says in a conversation in Allahabad in 1971, “Vivekananda has influence here in higher class, among the educated class. They talk about Vivekananda and this and that, nonsense…Here amongst the educated class there is influence of all these rascals, Vivekananda, Aurobindo, and… That is one defect…Because educated class means wine, women, meat, and Vivekananda allows this. That is the point. Vivekananda has no distinction of eating.”

Also read: Swami Vivekananda is not a Sangh Parivar icon. Liberal-progressives allowed his appropriation

Two sides spirituality

What we have here is a fundamental opposition between two views of spirituality and Hinduism. To put it at the most basic level, one is exclusive and the other inclusive. One viewpoint tends to exclude things (meat eating, different forms of God, different faiths, different personal habits, etc.), while the other tries to broadly include them. Vivekananda not only ate fish but also meat. It would be interesting to examine Vivekananda’s own views on the matter.

As Sankar describes in detail in his book The Monk as Man, cooking was one of Vivekananda’s favourite hobbies. And one of his favourite dishes was a spicy mutton curry, which he frequently prepared for his Western disciples and friends. Vivekananda advised Hindus at large to eat meat because he believed animal protein gave more strength and energy.

In The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda, there is a record of a conversation between Vivekananda and a disciple from East Bengal (now Bangladesh) about the question of non-vegetarianism and spirituality.

“Disciple: It is the fashion here nowadays to give up fish and meat as soon as one takes to religion…. How, do you think, such notions came into existence?

Swamiji: What’s the use of your knowing how they came, when you see clearly, do you not, that such notions are working ruin to our country and our society? Just see—the people of East Bengal eat much fish, meat, and turtle, and they are much healthier than those of this part of Bengal…

…Yes, take as much of that as you can, without fearing criticism. The country has been flooded with dyspeptic Babajis living on vegetables only…

All liking for fish and meat disappears when pure Sattva is highly developed, and these are the signs of its manifestation in a soul: sacrifice of everything for others, perfect non-attachment to lust and wealth, want of pride and egotism…. And where such indications are absent, and yet you find men siding with the non-killing party, know it for a certainty that herein, there is either hypocrisy or a show of religion.”

But isn’t renunciation of pleasures the sine qua non of spirituality? And isn’t the concern for the life of animals a worthy virtue conducive to Sattva guna (the mental quality of peacefulness and equilibrium, which is the soil of spirituality)? Vivekananda gave an unqualified yes to both of these questions. But he also made it clear that external renunciation and the display of spirituality is easy, while true inner renunciation and achieving spiritual truth is a Herculean task. And an obsession with the external led to the narrowness of the heart and a degradation of the intellect rather than universal humanity and spirituality.

Also read: Vivekananda wanted to wash Jesus’ feet with his blood. Even invited Christian missionaries to…

Internal and external purity

At a speech delivered in San Francisco, on 16 March 1900, Vivekananda gave an illustration of this tendency. “In our country, there are vegetarian sects. They will take in the early morning pounds of sugar and place it on the ground for ants, and the story is, when one of them was putting sugar on the ground for ants, a man placed his foot upon the ants. The former said, ‘Wretch, you have killed the animals!’ And he gave him such a blow, that it killed the man.”

He said that external purity is easy to achieve so the world rushes towards it. But grappling with the mind is hard work. Vivekananda also shared that when he was a boy, he had great regard for Jesus Christ but when he read the wedding feast in Bible, he closed the book and said, “He ate meat and drank wine! He cannot be a good man.”

“Bathing, and dress, and food regulation—all these have their proper value when they are complementary to the spiritual. …. That first, and these all help. But without it, no amount of eating grass… is any good at all. They help if properly understood. But improperly understood, they are derogatory,” he said.

Perhaps the last word should belong to Vivekananda’s guru Ramakrishna, considered by many as the greatest mystic of modern times. To one of his devotees wishing to advance on the path of spirituality, he said, “Do not give up anything. Things will give you up by themselves.”

This article has been written by the author of the recently published book Vivekananda: The Philosopher of Freedom. Views are personal.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)