The first Covid-19 case in India was confirmed on 30 January in Thrissur, Kerala. Subsequently, the total number of cases crossed 500 by 23 March, and a surge seemed imminent. Against this backdrop, on 24 March, the Prime Minister announced a nation-wide lockdown for 21 days. We have now spent more than two weeks in the lockdown, while India’s disease load has grown significantly.

The government is facing tough choices regarding what social-distancing policies, and economic support strategies, to pursue beyond 14 April. It is being recognised that not all parts of the country have been impacted uniformly by Covid-19, and voices have emerged calling for the implementation of a more selective lockdown.

In the policy conflict between the scalpel (selective lockdown) and the blunderbuss (general lockdown), the scalpel must surely eventually prevail, but the timing and manner of its use must be guided by adequate information.

Also read: App for milk, vendors at the gate — how Delhi-NCR’s hotspots managed on Day 1 of ‘sealing’

Tracking the Covid trends

Over the past week, we have been studying data on the spread of Covid-19 in India – as recorded in the patient database of covid19india.org – and have realised that disease spread has indeed been uneven, both across space and time.

On midnight of 5 April, 323 Covid-afflicted districts (containing 50 per cent of India’s population) had recorded a total of 4,218 cases. This implies an average case-load of 13 per affected district. Given that, we categorised the affected districts into four clusters – heavily-affected districts with more than five times the average case-load, significantly-affected districts with 2.5 to five times the average, moderately-affected ones with 1 to 2.5 times the average, and mildly-affected districts with no more than the average.

We found that the heavily-affected districts include the metro areas of Delhi, Mumbai, Indore, Jaipur, Chennai, and Pune. We had only state-level data for Jammu and Kashmir, and Telangana, which clearly indicated that most of their districts were also heavily-affected by Covid-19. The 20 significantly-affected districts included Agra, Ahmedabad, Bengaluru, Coimbatore, and Thane. Next, 42 districts were moderately-affected, and finally, 188 districts were mildly-affected.

The unevenness in the spread of Covid-19 is also borne out by the fact that Jammu and Kashmir, Telangana, and an additional 16 per cent of all the districts in the rest of India together reported 86 per cent of all Covid cases in the country.

Also read: Haryana doubles salaries of healthcare officials and workers fighting Covid-19

Skewness of disease-load

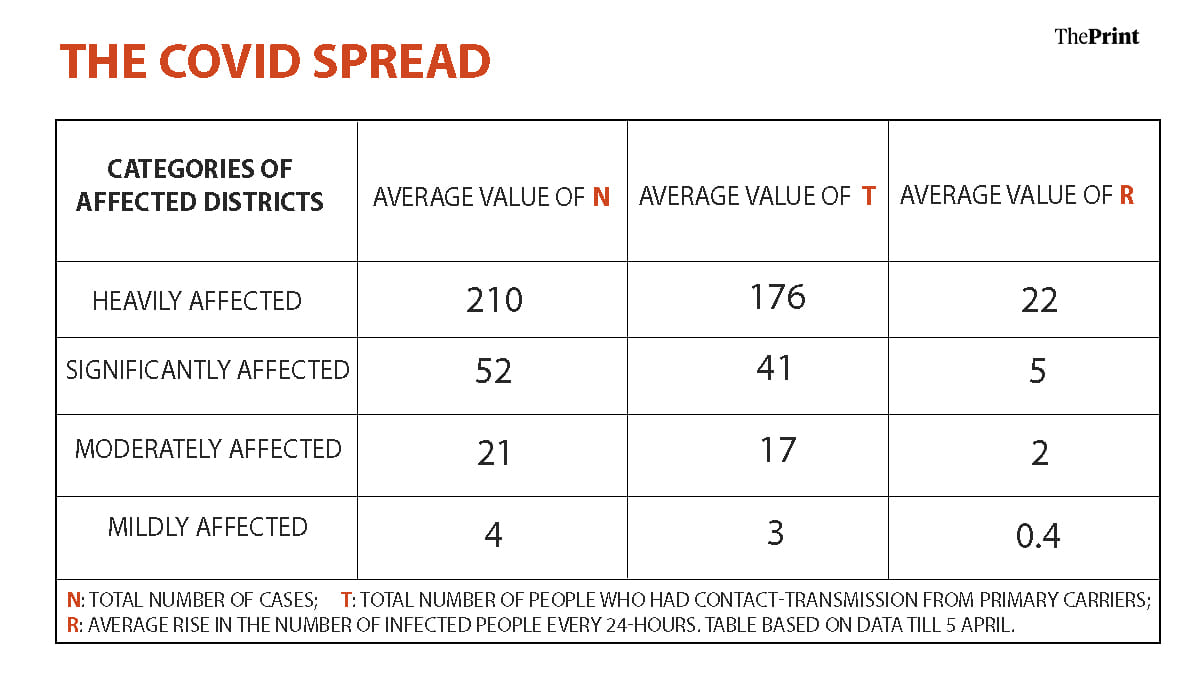

At the district-level, there was a high correlation between the total number of cases (N) and the total number of people (T) who had contact-transmission from primary carriers (predominantly Indians returning from disease-burdened foreign countries). A high correlation also existed between N and the average rise (R) in the number of infected people in every 24-hours in the one week preceding 5 April. The following table clearly shows the skewness of disease-load (in these different dimensions) towards the more heavily affected districts.

Also read: Coronavirus: Latest updates on cases in India, all you need to know about COVID-19

Selective lockdown eventually

Given the uneven spread of Covid-19 across India, the government should understandably be tempted to pursue selective lock downs in different parts of India. We, however, want to record the following concerns.

First. A principal reason behind proposing a selective lockdown is of course to ensure that some economic activity (especially production of essential commodities, and of gainful employment) can carry on in the unaffected/mildly-affected parts of the country.

But the gains arising from these activities (stock of new products and income) have to be distributed over the entire country, without letting the people of an unaffected district co-mingle with those in an affected pocket. The logistics of achieving such concurrent segregation and assimilation will be a challenge. The experience of other countries that have undertaken such selective lockdown needs to be studied carefully.

Second. We should be concerned that the disease spread is accelerating in quite a few districts. Some of it is obviously due to the new sources of the virus like the Tablighi Jamaat at the Nizamuddin Dargah in Delhi. The fact is that the impact of such clusters and of other potential risks arising due to the movement of migrant labourers is yet to play out. We cannot quite predict how the disease load in already-afflicted districts will increase, and how many new districts will be affected due to such new shocks.

It may be prudent to continue with the current lockdown for at least one more week. This will give the government time to: (i) determine how the new sources will impinge on the uneven spread of Covid-19 in India, and (ii) think through the efficiency goals, the fairness issues, and the precise logistics of implementing selective lockdowns in different parts of the country.

Jyotsna Jalan is a Professor of Economics at the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta and Co-Director of CTRPFP. Arijit Sen is a Professor of Economics at the Indian Institute of Management Calcutta. Views are personal.

While its nice to propose this strategy, but author forgot that any incident during this period takes about 15 days to show its effect. Like Markaz event ended on 16 March and showed its effect 1 April on wards, similarly the mass exodus of laborers will show its effect by April 15 to states that yet seem to be less affected. Its is not easy to lock down again after reopening. Its better to get rid of this altogether, May be North East can be opened but rest would be risky adventure.

The article cogently presents persuasive data analysis. The data indicates that there is no need to continue country wide lock down. However, one can look at the issue from another point of view and reach the similar conclusion.

It is a fact that there is no medicine or vaccine available today for Covid-19; all that can be done is preventive to avoid getting infected with it -like follow self quarantine or self distancing from others so that virus runs its course without getting a host body and dies eventually. The instruments for protections are just using masks, gloves and following cleanliness practices. Suppose we assume that the entire country is infected (whether tested or not) and ask everyone to strictly use mask, gloves and follow cleaning practices, we can effectively contain spread of virus, with or without people mixing up together. Even today, we have so many people out like policemen, service delivery boys, workers and staff in essential services and of course, media people who just use mask, gloves etc and do their work and yet, no one is known to be affected by corona! This means that virus can be controlled by strictly enforcing use of mask, gloves etc and allowing people to move about with some restriction, rather than locking down everything. By now, the entire country has awakened to the dangers of the virus and the need to protect oneself from it by using simple techniques. Of course, we need to protect old, vulnerable and younger population from it and they must be barred from coming out. Going by this common sense approach, there is a strong case for partial lifting of lock down with certain conditions and allow normal economic activities to resume. In cities, there could be restrictions like each office should not allow more than 50% of its staff to attend office on any given day, those who can work online, must be allowed to work online etc etc. Impose fine of say, 10,000 rupees per violation of mask usage etc. Overall, a common sense, pragmatic and forward looking solution is required rather than just dumb thinking like ‘testing testing and testing’ or indiscriminate use of hand sanitizer!