The Supreme Court judgment on Babri Masjid-Ram Janmabhoomi land title dispute can be interpreted in two different ways.

One is to read it as a political rationalisation in favour of Hindutva-driven majoritarianism discourse, where the argument that the birthplace of Lord Ram is a matter of Hindu faith has finally found a legal validation. Two, there is an equally powerful technical dimension of this judgment, which is a bold attempt to separate the disputed site from the structure called Babri Masjid.

The first, the political reading of the verdict, is not entirely incorrect. Hindutva has finally achieved its three-fold agenda: banning triple talaq, scrapping of Jammu and Kashmir’s special status through Article 370, and state-sponsored Ram Temple on the site where Babri Masjid once stood. But this straightforward political interpretation is rather simplistic. It does not help us in understanding the complex political processes, which lead to the triumph of Hindutva. Instead, we are left with existing binaries: faith versus law, nationalist versus liberals, and so on.

Therefore, we must make a clear distinction between the Supreme Court’s Ayodhya judgment and the political discourse it is going to generate.

Let us look at the four technicalities of the judgment before rejecting it as a political statement.

Also read: There are 3 claims to Ayodhya — law, memory & faith. It’s not a simple Hindu-Muslim dispute

Technicality 1: Supremacy of secular law

Unlike the media reports, the Supreme Court categorically rejects the faith-based claim. It is argued that the faith of a community cannot be taken as a legal yardstick to determine the status of disputed places of worship. It is noted:

The court cannot adopt a position that accords primacy to the faith and belief of a single religion as the basis to confer both judicial insulation and primacy over the legal system as a whole. …in a country like ours where contesting claims over property by religious communities are inevitable, our courts cannot reduce questions of title, which fall firmly within the secular domain…to a question of which community’s faith is stronger.

The secular law, therefore, emerges as the basic principle to arrive at a legal conclusion in this case.

Also read: The tale of two Ayodhya archaeologists who changed the way we dig up India’s Hindu history

Technicality 2: Centrality of law, not archaeology/history

The Supreme Court acknowledges that the Babri Masjid dispute has historical and archaeological dimensions, which makes it politically sensitive. However, it clarifies that the multicultural foundation of Indian society must be governed by the legal-constitutional principles. The judgment says:

For a case replete with references to archaeological foundations, we must remember it is the law that provides the edifice upon which our multicultural society rests. The law forms the ground upon which multiple strands of history, ideology, and religion can compete.

Technicality 3: Inner and outer courtyard of Babri Masjid

The Supreme Court envisages the disputed site as a single entity. This comprehensive view helps the court to place the conflicting claims in a legally workable perspective. The court makes two clear observations: (a) ‘the Hindus have been in exclusive and unimpeded possession of the outer courtyard where they have continued worship’, and (b) ‘the inner courtyard has been a contested site with conflicting claims of the Hindus and Muslims.’

These inferences are interpreted more broadly in relation to the two events: the placing of the idols of Ram and Sita inside the Babri Masjid on 22/23 December 1949, and the demolition of the Babri Masjid on 6 December 1992. The court observes:

The allotment of land to the Muslims is necessary because though on a balance of probabilities, the evidence in respect of the possessory claim of the Hindus to the composite whole of the disputed property stands on a better footing than the evidence adduced by the Muslims, the Muslims were dispossessed upon the desecration of the mosque on 22/23 December 1949 which was ultimately destroyed on 6 December 1992.

Also read: How a Hindu party wanted Ram Mandir but didn’t raise it in India’s first election under Nehru

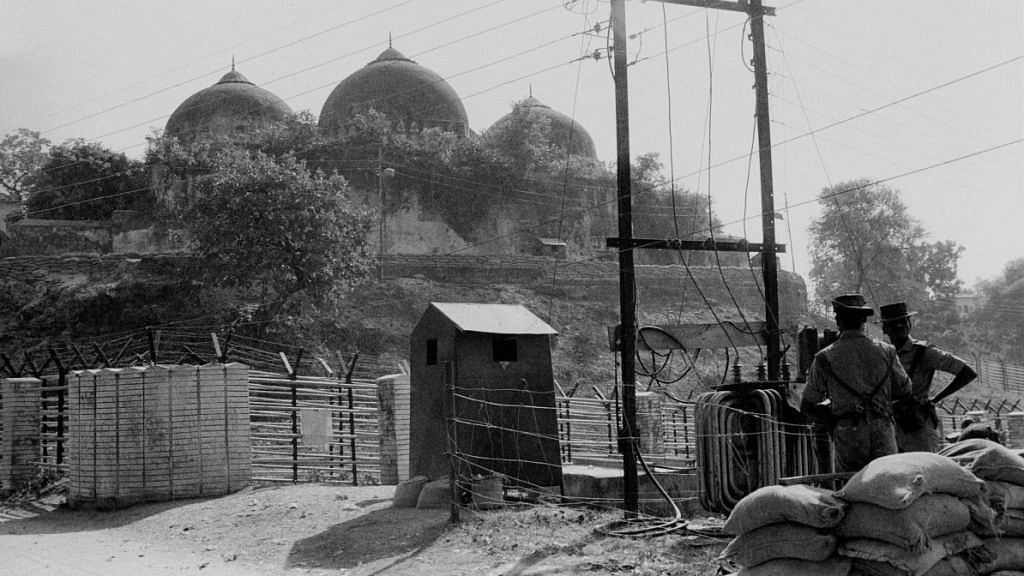

Technicality 4: Structure versus the site

The Supreme Court makes an interesting distinction between the disputed site and the structure of Babri Masjid. Although it accepts the claims of Hindus on the disputed site, it gives adequate attention to the demolished structure as a mosque. This is one of the crucial aspects of the Ayodhya judgment.

We must remember that the structure of the Babri Masjid became contested only in 1949 when idols were stealthily placed inside it. After the demolition of the mosque in 1992, the Hindu as well as the Muslim political elite transformed it into a land dispute.

The Supreme Court, unlike politicians, makes a distinction between the site and the structure. It goes beyond the established political binaries and proposes a viable solution in favour of a reconstruction of a mosque.

Yet, it is problematic

These four technicalities, no doubt, introduce us to some positive aspects of the judgment. Yet, it is a problematic verdict primarily because it has established the Ayodhya dispute as a historical conflict between Hindus and Muslims. The Supreme Court wants us to believe that ‘the lands of our country have witnessed invasions and dissensions. Yet they have assimilated into the idea of India everyone who sought their providence, whether they came as merchants, travellers or as conquerors.’

The Supreme Court, it appears, conceptualised Hindus as a faith community, Muslims as a historical entity of ‘outsiders’, and the two as naturally antagonistic to each other.

The author is a Fellow at the Nantes Institute of Advanced Studies, France (2019-2020) and Associate Professor, CSDS, New Delhi. Views are personal.