As the national elections of 2019 draw close, and incumbents prepare to face voters again, a straightforward question follows: how many people does a Member of Parliament really represent? On average, an Indian parliamentarian today represents constituencies with more than 1.5 million or 15 lakh eligible voters, or close to 2.5 million or 25 lakh citizens. This is more than the population of over 50 countries across the world and almost four times the number of citizens a Member of Parliament represented in the first Indian election in 1952.

The sheer size of the electorate that each MP is supposed to represent may be seriously undermining representative democracy in India.

Indian Members of Parliament (MPs) represent many more people than MPs in other countries such as Britain, Canada or the US that elect a single representative from each geographically determined constituency. In Canada, each MP represents about 97,000 eligible voters whereas a British MP is accountable to approximately 72,000 voters. Each member of the House of Representatives in the United States has to win a plurality in constituencies with an average of about 5.8 lakh electors, which is about a third of the size of the average parliamentary constituency in India.

Increasing electorate since 1952

In 1952, most MPs represented somewhat equal number of people (about 4.32 lakh eligible voters). Since then, not only has the size of the electorate increased for all constituencies, but there is also greater variation in the number of voters each MP represents.

An extreme example from 2014 is the large gap between the parliamentary constituency (PC) of Lakshadweep, which had less than 50,000 eligible voters, and Malkajgiri (now in Telangana), which had over 30 lakh eligible voters, an electorate the size of the entire population of Mongolia.

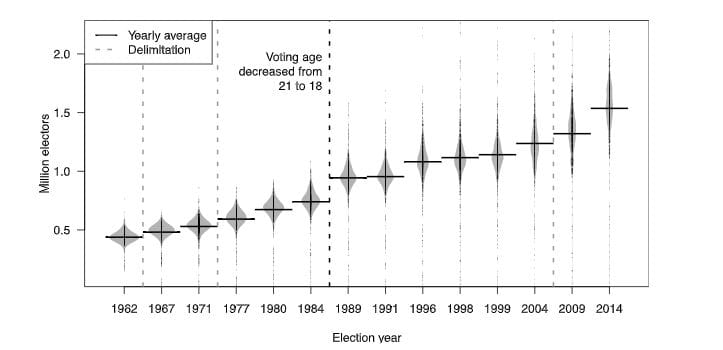

The accompanying table taken from Chapter 2 of the forthcoming book Constructing a Majority: A micro-level study of voting patterns in Indian elections shows an increase in the number of eligible voters across Indian PCs from 1962 to 2014. For each year, our bean plot shows the variation in the electorate across all PCs, ranging from the one with the smallest electorate to the one with the largest electorate. The small black dots that appear in the vertical line in each bean show the size of the electorate for individual PCs – the longer the line, the greater the discrepancy between the smallest and the largest PC. The horizontal line in the middle of each bean indicates the average number of electors across all PCs in that particular election year.

The grey shape of the beans shows the distribution of values across all the PCs for that year. A more compact bean means less variability in the size of PCs. For example, in 1962, the 494 PCs had an average of 4,37,400 electors (shown with the horizontal line cutting across the bean right below 0.5 million or 5 lakh voters). The bean is quite wide and compact, indicating that most PCs were of similar sizes. There were some outliers: the smallest PC – Mahasu constituency in Himachal Pradesh – had only 1,60,883 electors (represented by the bottom black dot), while the largest PC – Bombay City North in Maharashtra – was almost five times bigger, with 7,64,016 electors (represented by the top black dot).

As we can see in the figure, the size of the PCs has grown dramatically over time. In 1971, the average PC had more than 5,00,000 electors, which rose to 7,39,600 in the 1984 elections.

In 1988, the voting age was lowered from 21 to 18. This led to a substantial increase in the size of each constituency, with the average constituency now home to almost a million or 10 lakh voters. There was little change between 1989 and 1991, but the average electorate in a PC passed the one-million or the 10-lakh mark in 1996. For the 2014 elections, the average PC in India had more than 1.5 million or 15 lakh voters and eight PCs had over two million or 20 lakh voters.

Also read: Just 6 MPs boast of 100% attendance in 16th Lok Sabha — four from BJP, none from Congress

Increase in number of representatives

The number of MPs elected to the Lok Sabha has also increased, but this increase is far less dramatic than the growth in the population within each constituency.

When the first Indian national elections were held in 1952, there were 401 territorial PCs. In the 1952 elections, 86 of the 401 constituencies were double-member constituencies, and one was a triple-member constituency, so candidates were competing for a total of 489 seats (Election Commission of India, 1951). The number of elected seats in the Lok Sabha increased to 494 in the 1957 elections, then to 520 in the 1967 elections, and so on, reaching 545 – the current number – in the 1996 elections.

Anglo-Indian representation

Of the 545 seats in the Lok Sabha, candidates for 543 are elected from single-member territorial constituencies. The two remaining seats are filled by members of the Anglo-Indian community who are nominated by the President of India. Why should the Anglo-Indian community continue to have two seats almost 70 years after the first election, especially when according to some estimates there are less than 2 lakh Anglo-Indians? Reservations for the Anglo-Indian community came about as a result of the intense discussions on reservations for various groups during the Constituent Assembly debates.

Still, keeping these seats is clearly in the interest of those in power. If the government in power- the BJP, the Congress, or a coalition-is aligned with the President, it is likely that it will get two additional votes in Parliament from the nominated members. In a divided legislature, where governments may need every vote to survive, the Anglo-Indian members afford the ruling party some cushion. This is also quite an unusual arrangement as none of the other parliament we have talked about – Britain, Canada, or the United States – nominate members to the Lower House.

Also read: Not Hindu-Muslim, this issue can become the polarising factor in 2019 elections

Representation crisis in Indian democracy

These numbers show that Indian MPs are unusual compared to other MPs in the world, and this has serious implications for representative democracy in India. For instance, it would anyway be very difficult for a candidate running for Lok Sabha elections to reach out to as many as 1.5 million or 15 lakh voters. Managing to do so during the very short official campaign period is even harder. If candidates are unable to effectively reach out to voters and educate them about themselves and their campaigns, it impairs the ability of the voters to make informed decisions about who should represent them.

A more dangerous consequence is that, once elected, no Member of Parliament can effectively represent the interests of so many people. If candidates cannot reach out to enough voters, and elected MPs cannot really represent the interests of enough people in their constituencies, then elections may become less about hearing the voices of the voters and addressing the issues they care most about. This representation crisis might be the reason why turnout in general elections in India is lower than state and local elections.

Pradeep Chhibber is with the University of California, Berkeley. Francesca Jensenius teaches at the University of Oslo. Harsh Shah, an alumnus of the University of California, Berkeley, is a political analyst and works in the private sector.

This is the first in a series of articles in ThePrint that will provide readers with comprehensive, research-based information about the Indian elections since 1962. The articles will also draw upon recent findings from Constructing a Majority: A micro-level study of voting patterns in Indian elections (forthcoming Cambridge University Press) by Francesca Jensenius, Pradeep Chhibber, and Sanjeer Alam.