These last few weeks have been busy for the navy. It has just commissioned the INS Mormugao, a 7,400-tonne destroyer. Three months ago the prime minister commissioned the country’s first indigenously built aircraft carrier, the 45,000-tonne Vikrant.

The navy may also be about to commission its second nuclear ballistic missile submarine, the INS Arighat — the precise date will remain secret. Meanwhile, the fifth conventional Scorpene submarine, the INS Vagir, has been delivered to the navy and will be commissioned early next year along with the first of a new class of frigates.

There is no previous period when the navy acquired so many major, front-line ships and submarines in such short order. Last year, 2021, was also busy as it saw the commissioning of two Scorpene submarines and a destroyer. This would suggest that the navy’s expansion is gaining momentum, and in some ways that would be true. But one must also look at the longer-term picture. Compared to 2021 and 2022, the previous two years saw the commissioning of just one submarine and a 3,300-tonne corvette, while 2018 saw no major addition to the fleet. Broadly speaking, the trend since 2011 continues, of commissioning an average of two major warships annually.

That is an improvement on the decade before, but each ship still takes too long to get built: Seven to nine years for a destroyer, frigate or corvette — more than twice what it takes for China. Even then, key accompaniments are missing at the time of commissioning, like the right long-range, air-defence missiles, heavyweight torpedoes, anti-submarine helicopters and even carrier-borne aircraft. It has not helped that the INS Vikramaditya, the aircraft carrier acquired from the Soviet Union and commissioned in 2013, has been in dry dock repeatedly, the latest being for an extended period. One report said recently that no aircraft has landed on either of India’s carriers in the last two years.

Still, you could say that India is steadily building its naval strength. The next batch of seven 6,600-tonne frigates will introduce modular construction, thereby speeding up shipbuilding by about two years. While Mazagon Dock remains the primary builder of destroyers and frigates, Garden Reach Shipbuilders & Engineers, Cochin Shipyard and Goa Shipyard are all capable now of building bigger, more complex vessels, as is the nuclear submarine-building complex at Visakhapatnam. To that list must be added a ship design and yard facility developed by Larsen & Toubro near Chennai.

Also Read: Is India’s defence business a good news story or bad? Perhaps both, but changing for the better

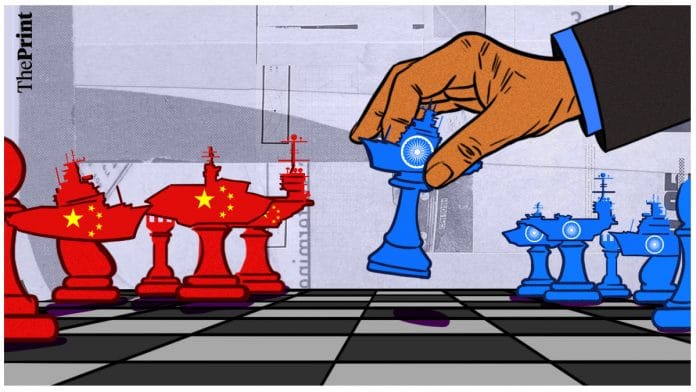

None of that compares with the speed of the naval build-up by China, which last summer launched its third aircraft carrier — bigger than India’s two carriers combined, with more advanced technology that will enable the launching of aircraft at shorter intervals, with more fuel and a heavier weapons load. Having already built very capable destroyers at breakneck speed, China is now planning for war on the sea with killer drones and unmanned vessels capable of linking with manned warships for networked attack. With Beijing also developing various facilities, including a naval base, around the Indian Ocean rim, India’s navy will be challenged in its home waters before long.

Yet, given limited defence budgets, there aren’t enough orders to keep the shipyards humming, although many smaller ships — like shallow-water craft for anti-submarine warfare — are on order. The under-sized submarine fleet in particular has mostly ageing boats that date as far back as the 1980s, but Mazagon’s submarine shed will run out of orders after delivering its sixth and last Scorpene submarine.

The follow-on order for another six has been repeatedly delayed; potential bidders are reluctant because of what they see as unacceptable terms. Meanwhile, the defence minister surprised observers recently when he said that India has started constructing what will be the fleet’s third carrier; little has been heard of this order before or since. Bids to win export orders from Malaysia, Brazil and the Philippines have been lost to the competition.

The challenges facing the navy therefore are manifold: Inadequate budgets, delays in placing orders and then in construction, poorly coordinated delivery schedules, and the challenge from China. These issues need debate, even as the navy celebrates the commissioning of major warships and submarines in quick succession.

By special arrangement with Business Standard

Also Read: End subsidies, handouts — what Budget 2023 must propose to bring deficit down to below 6%