New Delhi: At a crucial time when the world is relying on science to end the global pandemic, two of the world’s most reputed journals have taken a hit due to the dubious research works of three Indian scientists in the US, ThePrint’s Editor-in-Chief Shekhar Gupta said in episode 489 of Cut The Clutter.

Last month, two major studies were taken down from The Lancet journal and The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM). Both of these had serious implications for the medical advice being given to coronavirus patients, but both were flagged for data discrepancies.

Three Indian-origin researchers were the key drivers in both these studies. The researchers in question include Mandeep R. Mehra, a cardiologist with an MD from Harvard University; Sapan Desai, a surgeon and founder of a data analytics company called Surgisphere; and Amit Patel Chief of Cardiothoracic Surgery in University of Utah in the US.

Also read: Surgisphere, the Indian-American founded tiny data firm at the centre of HCQ-Lancet storm

The Lancet study

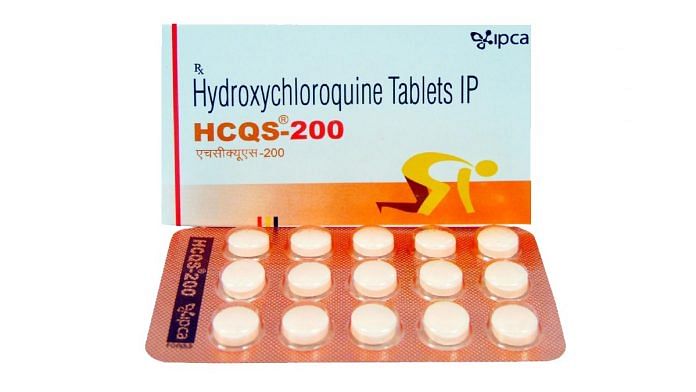

The Lancet journal had published a large study on hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), an antimalarial drug that has become controversial due to conflicting claims of its effectiveness as a treatment for Covid-19.

The study claimed to have looked at data from 671 hospitals across six continents. About 81,000 hospitalised patients were not given HCQ and 15,000 were given the drug.

Based on the data, the researchers concluded that HCQ was not benefiting anybody. However, they claimed that there was enough evidence to show that the incidence of heart rate irregularities and related deaths was considerably higher among those being given HCQ.

The study talked about the use of HCQ in combination with macrolides, a class of antibiotics in the azithromycin category.

As a result of this study, doctors around the world who were using HCQ as a possible treatment therapy stopped, Gupta said.

The World Health Organization too halted all their ongoing research involving HCQ that was part of their global SOLIDARITY trial.

Also read: WHO to resume HCQ trial for Covid it had paused after controversial Lancet article

Question raised on The Lancet study

India, however, did not stop using HCQ because ICMR did not accept it, Gupta said.

Soon, researchers across the world began to question it. Scientists and doctors from around the world wrote a joint letter to The Lancet saying that they were not convinced with this research.

They asked for the primary data on which the research was based to also be published, because discrepancies began to show up in the data.

For example, the number of deaths attributed to six hospitals from Australia was higher than what was reported in official records by that date.

The authors admitted that it was an inadvertent mistake, because data from a hospital from Asia was mistakenly added to data from Australia. But the researchers claimed that this did not affect the overall results of the study.

“Now, when that happened, a clinch in the armour opened up,” Gupta said.

When The Lancet asked the authors of the paper for the data, the latter were not able to furnish the data. The company Surgisphere cited client confidentiality and was unwilling to share this primary data.

“This study became a big shot in the arm of the anti-HCQ community. A lot of people who have been given that medication stopped it. It is possible that the drug may indeed be beneficial or not harmful. Many of those people who have died subsequently, may have survived if they were continued on this treatment,” Gupta said.

“We don’t know if HCQ works, but we know now that the research that shows that HCQ does serious harm was fake,” he adds.

A report in The Guardian also found that the key employees of Surgisphere included a science fiction writer and an adult movie star.

The authors of The Lancet study have now written an apology and withdrawn the study. The Lancet also said they regret having published it. They took the study down.

Also read: ICMR & Lancet HCQ study aren’t at odds. One is on preventing Covid, other about treating it

NEJM study

Another study, which was published in The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), included the same three authors.

The research, published on 1 May, looked at whether the most popular blood pressure drugs in the world, called Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or Angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), can make people more susceptible to SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19.

The novel coronavirus uses the ACE receptors to latch on to human cells and infect them.

“Immediate questions arose that if you’re having these ACE inhibitors, do these drugs then weaken your body’s ability to deal with the coronavirus? Logically it would seem yes,” Gupta said.

The study, published by The New England Journal of Medicine on 1 May, claimed that taking these ACE inhibitors didn’t appear to increase the risk of death among Covid-19 patients, contrary to what some researchers had suggested.

This study was later retracted, because, here as well, the authors were unable to produce the primary data on which this study was based.

Also read: Everyone is cherrypicking studies on HCQ. But scientists are divided

Reputation of the journals

Both of these journals are very highly reputed. Set up in 1811, The NEJM has an impact factor of 70.67. On the other hand, The Lancet, which started in 1823, has an impact factor of 59.102.

Impact factor is an index that reflects the average number of times an article gets cited from the journal. It is calculated by dividing the number of times an article has been cited from a journal by the number of citable articles (not including editorials, correspondences etc) published by the journal.

By contrast, the Indian Journal of Medical Research has an impact factor of 2.

“All doctors, all medical personnel or health journalists believe The Lancet,” Gupta said. So how was The Lancet taken for a ride?

“If you see the Lancet editorials lately, those have become very politicised, very ideological, and very polarised,” Gupta said.

In the episode 484 of Cut The Clutter, Gupta had explained how HCQ got polarised simply because Donald Trump, without medical advice, was plugging it to the world. Meanwhile, PM Narendra Modi was giving this ‘humble drug’ to the whole world.

“It’s quite evident that The Lancet also let its guard down. The entire process of beginning to write this report, sending it to peer review and publication took just five weeks,” Gupta said.

It would seem that the editors of The Lancet may have liked the conclusion of the HCQ study, and thus lowered their guard, which resulted in them publishing a study that perhaps endangered many lives.

There is a cynical saying in science, ‘Publish or perish’. It means that scientists are always under pressure to publish — or else someone else will.

“But this is like publish and kill. You publish, and other people perish. Why should such respected journals be in such a hurry to publish this research, which looks dodgy to begin with?” Gupta said.

Watch the full episode here:

Respected Sir,

Thank you for your post on YouTube and article in The Print. They are an excellent summary and background of recent investigative reports regarding the June 2020 retraction of an article from each of The Lancet and The New England Journal of Medicine.

As you point out, commercial interests may have driven the two suspect articles. Your example — of the profits of a drug manufacturer rising from half a billion USD to ten billion USD if the article’s conclusions were believed — is a very credible representation of the business model driving today’s Big Pharma.

I respectfully submit that the same applies to countries, especially developing ones like India. A theme, oft-repeated in your YouTube video, is that the three authors common to the two retracted articles were Indians, or “desis” (the Indian term for Indians). That is strictly inaccurate. They are Indian-American, i.e., Americans of Indian ancestry, who received their medical degrees and training (including in ethics) in the USA, not India.

More importantly, hammering home that they are Indian may have the unintended consequence of hurting India’s prospects as it seeks to grow economically, by attracting investment and manufacturing from overseas. Consider this hypothetical: If the researchers were Jewish-American instead, would a leading Israeli journalist hammer home the point that they were Israeli? Ditto Italian-, Chinese-, Irish- or any other melded American.

Consider another hypothetical: You pointed out that the cost of manufacturing hydroxychloroquine is about INR 172 crores (USD 23 million), a tiny fraction of the average life-cycle profits of a US FDA-approved drug. Would any country other than India provide this drug so cheaply, even under (or, especially under) the acute distress of Covid-19, given its massive profit potential even if only mildly effective?

I respect your intent for transparency. But ONE-SIDED transparency in a hard-nosed world, sadly, does not earn plaudits; it only invites others to take the advantage.

This issue might be have been irrelevant to the India of yore. For most of its post-Independence history, India “has not mattered” in the world; it always had “potential”, which, sadly, never translated to meaningful prosperity for its people. But internal changes in the last half decade or so, coupled with world events, now give India opportunities to grow and flourish that never existed before. India has much more to lose now from Indian-bashing than before.

A solution is to seek a fuller and more complete transparency, and point a sharper and more explicit flashlight at where the true faults lie: In the inordinate influence of Big Pharma; the business models driving publication bias; and in the impaired peer review process at even the top journals, particularly the absence of formal scrutiny of data.

Here’s the next Indian joker: https://www.facebook.com/596454781/videos/10160163302864782/

Krishan Kumar Aggrawal is President of the Confederation of Medical Associations in Asia and Oceania (CMAAO). He says, “Corona also has a right to live, let it live with respect”