The punishment of a traitor is death”: Seventy-five years ago this month, a jagged piece of tin had been hammered into the forehead of Mir Maqbool Sherwani, bearing a hand-painted warning to Kashmiris to stop resisting their liberation. Like hundreds of others, Sherwani had been engaged in partisan groups holding off Pakistani irregulars rolling toward Srinagar. His brutal ritualised execution, the photographer Margaret Bourke-White speculated, might have been inspired by the “sight of the sacred figures in St. Joseph’s Chapel, on the hill just above.”

Fighting under the command of Major-General Akbar Khan—‘General Tariq’ to his men, taking his nom-de-guerre from Tariq ibn Ziyad, the ethnic-Berber commander folklore credits with having captured Gibraltar in 711 C.E—the irregulars who killed Sherwani had been ordered to save Kashmir for Islam.

“Their help to their brother Muslims”, Bourke-White acidly wrote, “was accomplished so quickly that the trucks and buses would come back within a day or two bursting with loot, only to return to Kashmir with more tribesmen, to repeat their indiscriminate ‘liberating.”

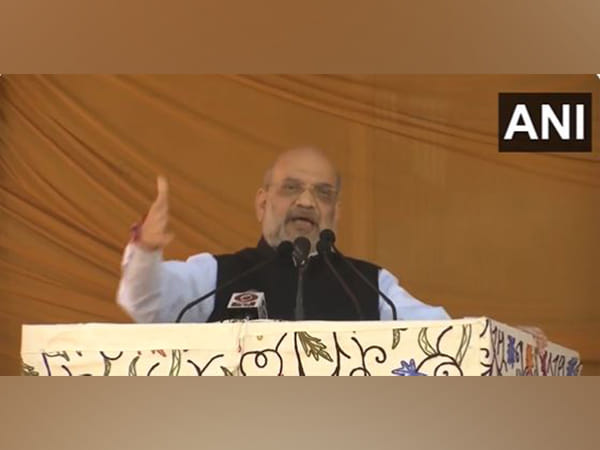

From a stage just a few hundred metres from the ground where Sherwani was killed, Union Home Minister Amit Shah announced last week that the government would not talk Kashmir with Pakistan—a sign that four-year-old back-channel secret dialogue between New Delhi and Islamabad has reached a dead-end.

Ever since the ceasefire on the Line of Control kicked back in last year—just months after Indian and Pakistani combat jets duelled over it after the Balakot crisis—National Security Advisor Ajit Doval and soon-to-retire Army chief Qamar Javed Bajwa are known to have been engaged in. Levels of violence have been low in Kashmir, and top jihadists have been jailed—signs Pakistan has dialled-down support for terrorism, to ensure the nuclear-armed States don’t lurch into the next crisis.

Kashmir concessions are necessary, Bajwa has been telling Western governments, to secure the peace—but that’s a price New Delhi isn’t willing to pay. New Delhi held firm on the line it drew, in the face of three wars, and a long-running insurgency—and now, the government believes, time is finally on its side.

Also read: Reservations for Kashmir’s Paharis meant to help them but it could start new fires instead

Drawing the line

Early in the autumn of 1947, the fire of Partition began to burn in Kashmir. In a telegram sent on 12 October, Islamabad recorded that Kashmir villages could be “seen burning from the Murree hills.” Then, Pakistan complained the Kashmir maharaja’s army was unleashing a “reign of terror” on Jammu Muslims. Kashmir’s government responded that the massacres were being carried not by its soldiers, but invaders arriving from Rawalpindi and the Hazara district. The response included a list of killings of Hindus and Sikhs in the Poonch-Rajouri mountain belt.

Later in the week, Indian signal intelligence intercepted desperate communications from outnumbered Gurkha troops of the Jammu Kashmir State Forces, pinned down by attackers at outposts near the town of Bhimber.

Then, on 22 October, troops of the 4 Jammu and Kashmir Infantry—made up of men raised from the violence-torn Poonch region—mutinied, killing their commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Narain Singh. The soldiers, as well as General Khan’s irregulars, now raced towards Srinagar, hoping to seize Kashmir before the dithering maharaja Hari Singh made his choice between India and Pakistan.

Five days later, the maharaja finally acceded to India. Led by Lieutenant-Colonel Dewan Ranjit Rai, troops of the 1 Sikh Regiment—soon joined by other units, and supported by volunteers like Sherwani—landed in Srinagar. Ferocious fighting followed. A long, grinding counter-offensive in 1948 led India to relieve the besieged garrison at Poonch, and seize back Bhimber and Rajauri. To the north, the Indian Army advanced towards the Uri-Tithwal axis.

Then-spy chief BN Mullik recorded that military commanders believed that had they “been allowed to resume their offensive in the following summer, they would have not been able to go much beyond the points which they had reached in October-November, 1948.” The new border—much the same as today’s Line of Control—coincided with the geographical limits of Kashmiri and Dogri-speaking populations, where pro-India political groups had influence.

Also read: PFI ban is no quick fix for jihadi threat. See how SIMI ban birthed Indian Mujahideen

The problem of victory

From the outset, Mullik has claimed, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru privately “agreed with the Jana Sangh’s views that Jammu and Kashmir should be fully integrated with India.” The accession of Kashmir, though, created a problem. “If India could claim Kashmir purely by virtue of the Maharaja signing the instrument of accession”, Malik noted, “then she would have to concede Pakistan’s claim over Junagadh for the same reason and also tolerate Hyderabad as an independent State in its very heartland.” That would have to be strategic suicide.

Early on, India responded to the conundrum by promising a referendum—but the war of 1947-1948 led it walk back. Foreign secretary Girija Shankar Bajpai wrote that the war meant the “offer of plebiscite could not remain open.” “If Pakistan wanted a decision by force, and that decision went against Pakistan”, he argued, “it could not invoke the machinery of the United Nations to obtain what it had failed to secure by its chosen weapon.”

Failure in the war of 1947-1948 didn’t deter Pakistan. Following the extension of India’s constitutional framework to Kashmir in 1953, India was compelled to mobilise troops to deter an attack on Kashmir. Like in 1947, Pakistani irregular forces attempted to seize the state in 1965. Islamabad unleashed covert warfare between these years, aimed at eroding India’s slow integration of the state into its national framework.

Even Pakistan’s defeat in the war of 1971, and the landmark Simla Agreement, proved to have short-lived consequences. From 1983, historian Avtar Singh Bhasin’s magisterial collection of documents reveal, terrorism had again become a major Indian concern.

The stakes grew after the two countries’ nuclear tests in 1998. In 1999, General Pervez Musharraf launched troops across the Line of Control in Kargil, hoping to ratchet-up pressure in the new, nuclear-weapons landscape. Following his failure to secure concessions on Kashmir at the Agra summit in 2001, a terrorist attack directed at India’s Parliament.

General Musharraf finally drew the right lessons in 2002-2003: While each war had failed to secure Indian concessions on Kashmir, they imposed an asymmetrical economic burden on Pakistan. A ceasefire followed on the Line of Control, along with a sharp drop in jihadist violence. The two countries again began a secret dialogue, conducted by Tariq Aziz and Satinder Lambah.

The negotiations—envisaging significant autonomy for both sides of Kashmir, in return for an end to terrorism and recognition of the Line of Control as a border—almost succeeded. The 26/11 attacks, though, destroyed process.

Following his rise to power, Prime Minister Narendra Modi reached out to Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif—facilitated by common friends like the industrialist Sajjan Jindal—hoping to restore momentum to the 2003 dialogue. Their plans were snuffed out, though, by the terrorist attacks in Pathankot, Uri and Pulwama.

Also read: For decades, Leicester built communal walls. Waves of immigrants made it more toxic

The new-old back-channel

Ever since the summer of 2018—when the polo-playing Inter-Services Intelligence officer Major-General Isfandiyar Ali Pataudi met his Research and Analysis Wing counterpart R. Kumar at a London hotel—India and Pakistan began re-engaging quiet back-channel dialogue to mitigate the risk of ending up at war. There have been a slew of informal, closed-door engagements throughout the year—in London, Bangkok, Doha and Muscat—involving political leaders and government servants from the two countries.

The contacts have fuelled optimism in some circles, only to be snuffed out. There were rumours Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif and Prime Minister Narendra Modi might meet at a recent multilateral summit—but the two leaders did not even exchange greetings.

Kashmir has proved an intractable issue. Bajwa, ThePrint reported in March, has been demanding that India reintroduce some of the features of the special constitutional status Kashmir enjoyed before August 2019. The Pakistan Army, he argued, had acted against terrorism—and refrained from pressuring India during the 2020 crisis on the Line of Actual Control.

The Indian government has been unmoved by these arguments, just as it has done since 1953 on. In New Delhi, policy-makers believe Pakistan’s terror rollback is tactical—a consequence of the threat sanctions and its dire economic straits—and not a strategic turn. The fears aren’t unfounded: Lashkar-e-Taiba infrastructure remains intact in Pakistan, and could easily be unleashed when geopolitical circumstances again favour the country.

As scholar Ashley Tellis has noted, India-Pakistan competition is not driven “by discrete, negotiable differences.” Instead, the problem is irreducible, “rooted in long-standing ideological, territorial, and power-political antagonisms that are fuelled by Pakistan’s irredentism, its army’s desire to subvert India’s ascendency as a great power and exact revenge for past Indian military victories.”

From Partition to the present, those grievances—and the potential consequences of each crisis—have grown for both states, and their peoples. The political incentives to secure them have diminished. Seventy-five years after the first shots of the India-Pakistan conflict were fired, peace has become just the punctuation between crises.

The author is National Security Editor, ThePrint. He tweets @praveenswami. Views are personal.

(Edited by Anurag Chaubey)