They want to kill me, they want to live my life,” runs the rap requiem, “opposition snitches talking on the phone, n**r, will that put me, my brothers in the wrong light.” The music and iconography are straight off the streets of Chicago or London: The men, unmistakably, ethnic Punjabi. First produced by the hit-man Ekene Anigbo for slain Brothers Keeper gang chief Gavinder Grewal, the anthem played through the revenge-killing of his rival, Randeep Kang.

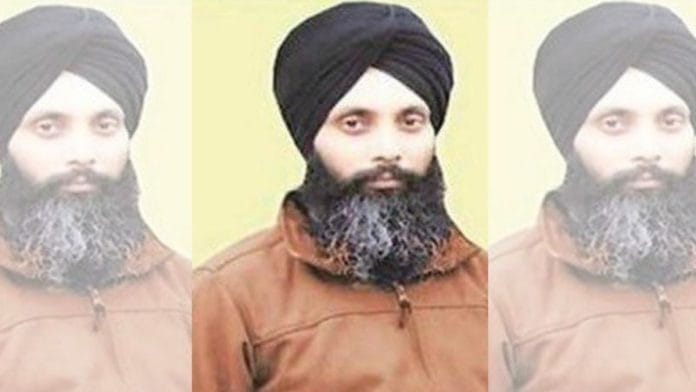

Last week, as thousands attended the cremation of Hardeep Singh Nijjar, who Indian authorities claim was at the heart terrorist networks operating in Punjab, there was little discussion of how the Khalistan movement has spawned a brutal gang culture spanning two continents.

Even though there have been claims Nijjar was assassinated by India’s intelligence services, some are suggesting that the causes might have been closer to home: A toxic war for control of well-funded Sikh religious institutions in Canada, waged through increasingly powerful criminal networks.

The battle had pitched millionaire businessman and former terrorist-turned-PM Modi supporter Ripudaman Malik against Nijjar. Last year, just months before Malik’s mafia-style execution by hitmen, Nijjar had publicly called his rival a traitor and demanded he be taught a lesson. Former partners and business associates also believed themselves aggrieved by Malik’s conduct of his businesses, the Khalsa Credit Union, the Satnam Education Trust, and Papillon Imports.

Even though we may never know the real motives for the killing, their similarities are startling: Nijjar was shot through the head as he waited in a parking lot—mirroring the circumstances of Malik’s murder.

Also read: India went to Myanmar to hunt down Manipur soldier killers. Now, it’s letting them slip away

The plumber who fought for Khalistan

Landing at Toronto’s Pearson Airport on 10 February 1997 on a fake passport identifying him as “Ravi Sharma,” Nijjer immediately filed for asylum, claiming to have been a victim of police harassment. Following the arrest of his brother Jatinder Singh, Nijjer claimed to have been repeatedly tortured by the Punjab Police. He paid bribes to officials, cut off his hair, and began hiding out at a relative’s home in Uttar Pradesh.

The story, reporter Stewart Bell writes, didn’t convince Canadian immigration officials. A medical report which purported to support Nijjer’s claims to have been electrocuted in the “testicles, [sic.]” the authorities determined did not seem genuine. And Nijjar’s account did not hold together under close questioning.

Eleven days after his asylum was rejected, he filed a fresh claim, claiming the right to live in Canada with his new wife, a British Columbia resident. Again, immigration authorities rejected the plea, deeming this a marriage of convenience. The courts too dismissed Nijjar’s appeal. Then, under circumstances which aren’t entirely clear, Nijjar obtained citizenship after 2001.

For his first years in Canada, Nijjar kept his head down, and ran a small plumbing business. From 2013, though, he became increasingly involved in pro-Khalistan groups, travelling to Geneva in 2013 to ask the United Nations Human Rights Council to acknowledge the 1984 riots as a genocide. The next year, he signed a letter announcing plans to hold a global referendum on Khalistan.

According to Indian police and intelligence services, Nijjar also became involved in terrorism. His name, officials say, first surfaced in connection with the investigation into the bombing of the Shringar movie theatre in Ludhiana in 2007. That prosecution collapsed, with three of the alleged perpetrators securing acquittals, and a fourth passing away while still in prison. The efforts to prosecute Nijjar, some Canadian law-enforcement officials believe, may have strengthened his asylum claim.

Large numbers of accusations of terrorism centred around Nijjar, though, continued to emerge. He was named in an investigation into the bombing of a temple in Patiala, and accused of a 2015 attempt to murder the cult leader Piara Singh Bhaniara, author of a Dalit-focussed alternative to the Guru Granth Sahab which he called the Bhavsagar Granth. Nijjar was also accused of having assassinated another member of a rival cult, the Dera Saccha Sauda, in 2015.

The Punjab Police and Intelligence Bureau say Najjar used links among organised crime groups in Canada to tie up with the gangster Arshdeep ‘Arsh Dalla’ Singh to stage attacks in India. Arshdeep is believed to live in Canada, where he disappeared while on a visit in 2017, travelling on a tourist visa.

Also read: Pakistan is being run by its very own Ayatollahs. But this time, Jihadists aren’t to blame

Fundamentalists take on traditionalists

Ever since Nijjar had arrived in Canada, diaspora politics had become increasingly tumultuous, with a new generation of younger fundamentalists taking on traditionalists. Things came to head in 1996 because of the intensity of the temple feuds, especially on whether elderly people should be able to share the langar community meal sitting on chairs and tables, as they ate at the McDonalds across the road, or only on a long floor mat. This had long been the practice at gurdwaras across Canada, and some in India.

The table debate exploded into a savage brawl, with a ceremonial sword being used to slice through a victim’s and another man being stabbed in the side. A teenage girl was hit on the head with a kitchen implement.

Edicts issued by Ranjit Singh, the Right-wing jathedar of the Akal Takht—the institution which believers see as their final source of temporal and spiritual authority—had banned the use of chairs. In some gurdwaras, like Ross Street in Vancouver, successful candidates asserted their legitimacy derived from the will of the Canadian Sikh community.

Fundamentalists, who lost those elections, had begun taking charge of the Gurudwara’s management several years earlier, putting up portraits of slain terrorists, including Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s assassins on the walls.

Liberal Sikhs like the businessman Harmohinder Singh Bains—who shaved his beard, and preferred cowboy boots—were appalled. “This is not a table and chair issue,” Harmohinder Singh Bains told journalist Antony DePalma. “The whole thing is about power, ego and money.”

There were similar debates playing out across the Canadian and United Kingdom diaspora. At one gurdwara, members argued over a resolution that would have allowed Sikhs who ran small shops selling cigarettes and liquor to join the congregation.

Liberals mostly lost the argument. Kashmir Singh Dhaliwal and Balwant Singh Gill, who had defied the Akal Takht and arranged langar seating for the elderly and disabled, were excommunicated by the Akal Takht. Fifteen years on, they reached out to the Akal Takht for forgiveness.

Also read: In Manipur govts have manufactured dystopia for decades, not peace. It’s showing now

Gangs, Guns and God

From the mid-1990s, around the same time as the Khalistan debate began to explode in Gurdwaras, a new generation of Punjabi-origin gangsters also began to transform the country’s crime scene. The brothers Ranjit Singh Dosanjh and Jimsher Singh Dosanjh were among the first lives claimed in gangland wars over control of cocaine distribution. Their alleged murderer, Bhupinder Singh Johal, went on to become a lifestyle icon for some youth—only to be eventually shot dead outside a nightclub.

A former police officer told the researchers Louis Pagliaro and Anne Marie Pagliaro that Gurdwara power-struggles had become tributaries watering the gangs. “It wasn’t uncommon for renowned toughs to receive the accolades and blessing of the temple priests and senior community leaders by day and then their blind eye by night as the same young men peddled drugs.”

Khalistan provided a language to address a new generation’s cultural anxieties—even if few members of the gangs were personally religiously observant. Indeed, as Renu Bakshi noted, many Punjabi gang members came from well-off families, who condoned their violent behaviour as appropriately masculine.

Last year, nine of the eleven most dangerous criminals named by police in British Columbia had ethnic-Punjab surnames—a startling number, given just 6.4 per cent of the province’s population identifies as Sikh.

The gangs of Canada also spawned an aspirational culture at home. Harjeet Mann, Jasdev Singh, and Sukhraj Dhaliwal, held on drug charges in the United States in 2005, were reported by residents of their village in Punjab to have been big donors to religious and social events. Gang names frequently recorded Punjab village affiliations—Dhak-Duhre, Sanghera, Malhi-Buttar.

The large number of killings of Khalistanis in recent weeks raises the obvious questions about possible Indian state involvement—but there’s even odds at least some of the killing has to do with fratricidal gang-world slaughter. Harvinder Singh ‘Rinda’, died of a drug overdose in Lahore. Harmeet Singh, also known as ‘Happy PhD’, also died in Lahore, shot dead, after a narcotics deal gone wrong. Paramjit Singh Pajwar was assassinated by gunmen outside his home in the Sun Flower Housing Society in Lahore.

Like Nijjar, scholar Ajai Sahni noted, each of these men was engaged in gun-running, narcotics trafficking and extortion—enterprises which gave motives to plenty of possible killers, beyond India’s intelligence services.

The author is National Security Editor, ThePrint. He tweets @praveenswami. Views are personal.

(Edited by Anurag Chaubey)