Eyes modestly turned away from the Grunge girls with their ripped fishnets and dark eyeliner, the colours of Acid House, and the wild hair of New Age Travellers, the army of the pious marched toward the Leicester University convention centre. Fitted out in shalwar-kameez, waistcoats, Afghan Pakul hats, and military-style boots, the occasional Abaya punctuating the ranks, the pilgrims had come to hear a preacher who promised he could open the doors of paradise without spending years in rigorous spiritual practice to excise the lust, envy, and greed that taints the soul.

To be martyred in the Kashmir jihad, Lashkar-e-Taiba chief Hafiz Muhammad Saeed told the young members of the Jamiat Ihyaa Minhaaj al-Sunnah (Movement for The Revival of the Prophet’s Traditions), would guarantee instant salvation, journalist Innes Bowen has written.

As he travelled through the United Kingdom in August 1995, the Lashkar chief called on his audience in Birmingham to “rise up for jihad” against the Hindus. In Huddersfield, he proclaimed “jihad and killing as first condition of our belief.” He went on, “To defeat infidels, it is our duty to develop all forms of arms and ammunition, including nuclear bomb.”

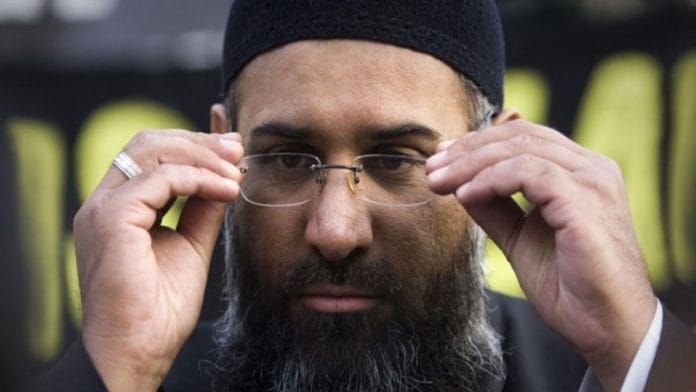

Last week, a court in the United Kingdom handed down a life sentence to jihad activist Anjem Choudary, holding him guilty of a massive campaign to send fighters and funding to the Islamic State. Through the efforts of Choudary and his organisation Al-Muhajiroun, or The Emigrants, sociologist Michael Kenny has recorded, “the flow of British activists to foreign lands increased from a periodic drip to a steady dribble.”

The story of how the United Kingdom—and other Western democracies—served as incubators for the global jihadist movement has, however, remained largely unexamined.

Even as the world struggled with the fallout of 9/11, Bowen has reported, members of the group that Saeed had spoken to in Leicester were training at Lashkar camps in Pakistan, recruited to stage suicide bombings in the United Kingdom. Fundraising for the Lashkar took place at mosques from Bradford to Oldham, court proceedings record. Large numbers of British volunteers fought in every major theatre of jihadist conflict since Afghanistan in 1979, with organisations recruiting cadres and appealing for terrorism financing in plain sight.

The government did almost nothing—until the fight for an Islamic State came home to England.

The cider-drinking jihadist

“Leopards don’t change their spots,” prosecution lawyer Tom Little told the jury at Choudary’s trial—Andy’s thoroughgoing transformation to Anjem, though, defied that claim. Choudary was the son of an ethnic-Punjabi market trader who lived in working-class south-east London’s Welling. Educated at the Mulgrave School in Woolwich, he defied the culture of underachievement in the Pakistani immigrant milieu, and gained admissions to medical school. Later, he switched to studying law at Southampton University, sharing a flat with a group of students in the Derby Road sex-work district.

Friends later recalled the fun-loving, cider-swilling, sexually-freewheeling ‘Andy’ with affection. “His digs were reminiscent of the Young Ones or Animal House,” counter-extremism activist David Toube remembered.

“There was a sofa in the living room which was gradually disassembled into its component parts during the course of the year. Mysterious graffiti used to appear on the walls.”

The Islamist made little effort to hide his past: When photographs of him holding up a pile of pint mugs and a pornographic magazine appeared in the tabloids, Choudary openly acknowledged he’d once lived a life very different from the one he later advocated.

Exactly what brought about the erasure of Andy, though, remains unclear. Like many of his generation, Choudary was incensed by the publication of Salman Rushdie’s book, The Satanic Verses—though not enough, Toube notes, to trouble himself with writing about it for the student law magazine.

“The Rushdie affair was an early expression of what we now call identity politics,” philosopher Kenan Malik has observed. “Britons of a Muslim background growing up in the 1970s and ’80s called themselves Asian or Black, rarely Muslim. The Rushdie affair gave notice of a shift in self-perception and of the beginnings of a distinctive Muslim identity.”

Following his college years, Choudary became a key lieutenant of the Aleppo-born Omar Bakri Muhammad, who led the London chapter of the Hizb ut-Tahrir, an Islamist organisation committed to the creation of a caliphate. Later, in 1996, the organisation evolved into Al-Muhajiroun.

The former Islamist Maajid Nawaz recalls that Bakri’s followers operated much like a gang, brawling with Sikhs and Christians in London’s East End, harrying sex workers, and intimidating Muslim women who chose not to wear a hijab.

Ethnic-religious tensions had begun to rise among immigrant communities across England. For the first time, Hindu and Muslim immigrants fought each other on the streets, in brawls reported to have started because of a cricket match.

Also read: Pakistan has laid a trap for itself in Gwadar — by letting conspiracy theories dictate policy

The jihad tourists

Al-Muhajiroun, though, was far from the only jihadist voice preaching on England’s streets. The year before the Lashkar’s Saeed landed in London, another preacher from Pakistan had arrived at Blackburn town’s Jamia Masjid, the centre of its mainly Punjabi-Pakistani community.

Masood Azhar Alvi’s tour led him to London’s East End and Lancashire’s immigrant-Pakistani ghettos. Even though the Jaish-e-Muhammad had not yet been founded, Azhar was already something of a jihadist rockstar, and a close associate of Al-Qaeda’s Osama Bin Laden.

Like Saeed, Azhar made express calls to violence. “The youth should prepare for jihad without any delay,” he said in one speech, obtained by the British Broadcasting Corporation. “They should get jihadist training from wherever they can. We are also ready to offer our services.” At the prestigious Darul Uloom seminary in Bury, Azhar delivered a talk on the theological justification for killing.

Amid other things, Bowen reports, Azhar used his visit to London to obtain the stolen Portuguese passport he would use while travelling to India—eventually leading to his arrest in Kashmir.

Together with Saeed, anthropologist Darryl Li has recorded that the jihad tourists to England included Mahmud Bahaziq, the Hyderabad-born son of a Nizam-era bureaucrat who went on to become one of the Lashkar’s co-founders. Following a brief, one-night visit to the frontlines in Afghanistan, Bahaziq became involved in jihadist fundraising and recruitment, serving in Bosnia from 1992.

London School of Economics dropout Ahmed Omar Saeed Sheikh, the Azhar protége who went on to murder journalist Daniel Pearl, was in Bosnia at the same time as Bahaziq. There is no record the two met, but England had clearly become a melting pot for global jihadists by the mid-1990s.

Following 9/11, Al-Mujahiroun supporters regularly cheered for Osama Bin Laden, gathering outside the US embassy to burn replicas of the Stars and Stripes and the Union Jack while holding up placards “burn, burn USA” and “down, down democracy”—sometimes in Hindi.

Also read: Behind Paris Olympics train attack, an unfolding story—rise of new caliphate in Africa

The English campaign

English jihadists were soon involved in killings across the world. Andrew Rowe, an aimless former drug dealer, converted to Islam and went to Bosnia where he took up arms and was injured during fighting, scholar Raffaello Pantucci has recorded. Saajid Badat participated in the 2000 al-Qaeda plot to blow up transatlantic airliners. Birmingham resident Muhammad Bilal carried out a suicide attack on the Indian Army’s XV Corps headquarters in Srinagar in December 2000. Omar Sharif and Asif Hanif volunteered for a suicide attack in Tel Aviv, for Hamas.

The bombing of London’s transport system by an al-Qaeda-linked jihadist cell, using men who had trained at camps run by Azhar’s Harkat-ul-Mujahideen, finally led the United Kingdom’s intelligence services to pay attention to the problem. Large numbers of cases soon followed, counterterrorism expert James Brandon has written, illustrating the links between English Islamist networks, camps in Pakistan, and jihadists in the Middle East.

As the Islamic State rose, Al-Mujahiroun fed a new generation of jihad volunteers to the Middle East—but it also nurtured others who saw their homeland as the more important battleground. Al-Mujahiroun links were found in several attacks carried out by so-called lone wolf jihadists, inspired by the Islamic State.

Former Bouncy Castle salesman Siddhartha Dhar—who went on to become one of the Islamic State’s most brutal executioners—pushed Choudary to support the Islamic State. “When we descend on the streets of London, Paris and Washington the taste will be far bitterer because, not only will we spill your blood, but we will also demolish your statues, erase your history and, most painfully, convert your children,” Dhar said in a message released from Syria in 2015.

Even though he threw his weight behind the Islamic State, Choudary remained at home, carefully attempting to stay on the right side of the law—all the while subsidising his campaign for the caliphate with taxpayer-funded welfare. Living in a £320,000 house owned by his in-laws, Choudary for decades claimed some £25,000 per year in tax-free unemployment benefits until his first arrest in 2016. In 2021, after his release, he got a job with a religious charity but was incarcerated for a second time soon after.

The hundreds of jihadists Choudhury inspired, though, remain scattered across England and the world. Their story has far from ended.

Praveen Swami is a contributing editor at ThePrint. He tweets @praveenswami. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)

Labour is back in power. This will only make things worse. Muslims vote en masse for Labour and it also has leaders like Jeremy Corbyn who justify and extoll Islamic jihadi terrorism.

No wonder, patriotic Englishmen are on the streets protesting against Muslim immigrants. Quite unfortunately, the Left-liberal media portrays the patriotic British as thugs, hooligans and rioters while keeping mum on the nefarious activities of the Muslim immigrants.

Londonistan has for long been a hub of Islamic jihadist activities. Has contributed significantly to both the finances as well as the manpower of various jihadi terrorist outfits for over three decades now.