Sabarimala verdict is judicial overreach. If legislating from bench is bad enough, pontificating from it is worse.

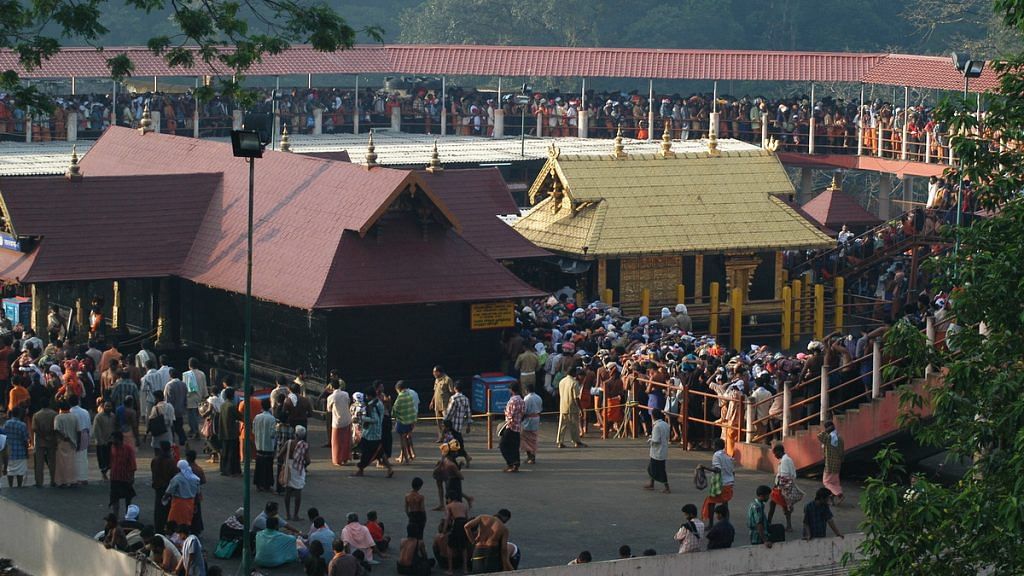

The more I think of it, the stronger are my fears that the Supreme Court’s verdict in the Sabarimala case will hurt the very Indian republic that allowed a deeply iniquitous tradition to be overturned, allowing women equal rights to worship at the Sabarimala temple in Kerala. I am not a conservative defender of religious traditions. Far from it, I say this as a liberal nationalist with deep convictions in the Enlightenment values enshrined in the Indian Constitution.

Why? Because the court’s decision further distances constitutional order from a large part of society that remains wedded to tradition. And why is that a cause for concern? Because both a religious conservative and a liberal have one vote each, liberals are generally outnumbered and thus electorally outgunned. Democracy amplifies social reaction, and creates governments, laws, law enforcement officials and even judges who are likely to side with what is popular than what is constitutional. If you don’t believe me, just read the news. We are already in the middle a moral panic where there is a finite risk that the current Constitution of India could be substantively amended if not replaced, almost as the immune reaction of an age-old civilisation that didn’t undergo the same intellectual-historical journey as western Europe.

Also read: Women have a right to pray, can now enter Sabarimala Temple, rules Supreme Court

In arriving at the decision to permit women into the Sabarimala temple, the majority judgment declared that “the subversion and repression of women under the garb of biological or physiological factors cannot be given the seal of legitimacy. Any rule based on discrimination or segregation of women pertaining to biological characteristics is not only unfounded, indefensible and implausible but can also never pass the muster of constitutionality”.

Fine. Now let’s say a woman from Ladakh, an Indian citizen and follower of Tibetan Buddhism, goes to court and challenges that she too ought to have a chance to reincarnate as the next Dalai Lama, will the Supreme Court of India rule in her favour?

Or a Roman Catholic woman from Goa files a petition in the courts against the church, claiming “discrimination and segregation” and demanding the right to be ordained a bishop, or a fair chance to become the next Pope? Or a Bohra woman who claims that she too should have a shot at being a Syedna? Or for that matter, Hindu women petition in the courts because they are practically barred from becoming Sankaracharyas?

Also read: With Sabarimala ruling, Supreme Court is doing its bit to push back patriarchy

Will the Supreme Court uphold its own principle and open the floodgates of global religious reform? And if it decides that women can indeed become Dalai Lamas, Archbishops or Popes, and the concerned religious authorities refuse to comply, will it haul them up in contempt of court? The only country I know that goes in this direction is the People’s Republic of China, not exactly an exemplar of liberal values.

If the Supreme Court really wants to apply this across the board, regardless of religion, then it becomes a global ‘judiciopapist’, swinging its sword of reason over the heads of all religious faiths around the world. If it limits the application of these principles to those who it determines as Hindus (even if they self-identify differently), then it paradoxically violates the very principle — equality before the law — that it intends to uphold.

You don’t have to be from the Hindu Right to see this is as both absurd and unjust. As the dissenting judge, Justice Indu Malhotra pithily wrote: “the equality doctrine enshrined under Article 14 does not overrule the Fundamental Right guaranteed by Article 25 to freely profess, practice and propagate their faith, in accordance with the tenets of their religion”. The Indian Constitution is certainly founded on reason, but it does not impose it on people.

Some people will ask what is the harm in the courts doing what politicians and social leaders lack the will to do. The harm comes from the high risk of unintended adverse consequences.

The British colonial government could abolish sati because Governor-General Lord William Bentinck didn’t have to go back to the people after five years seeking re-election. I would say that even the Constituent Assembly was able to incorporate far-reaching social reformist sections in the constitution because its somewhat-elected members didn’t care too much about their electoral prospects.

Today, thanks to democracy and universal suffrage, religion easily enters politics. The state of Punjab in an ostensibly secular Republic of India has enacted a sacrilege law. Some years ago, ‘blasphemy’ was made an offence under the Information Technology Act, and no one in Parliament or Rashtrapati Bhavan asked just how a secular state could logically have blasphemy as an offence in its statutes. If a majority of the voters feels threatened by changes imposed by the Indian republic, they can do something about it. And the outcome won’t be more liberal.

At a deeper level, the court is a poor substitute for grassroots social reformers. I have previously argued that “attempts by the state at a ‘social revolution’ only weaken efforts of social reformers who belonged to various communities. From Buddha to Kabir, from Guru Nanak to Narayana Guru, India has historically seen social reformers emerge as a response to orthodoxy and rigidity. Independent India has seen fewer of them, perhaps because the Indian republic has arrogated that responsibility to itself”.

Also read: Indian judiciary doesn’t need to fear the government; it needs to be afraid of itself

Why would the marginal social or political leader take up unpopular causes when you can easily punt it to the court?

Justice Malhotra was right when she ruled “that the grievances were not justiciable” as opposed to her two colleagues who felt that “the law and the society are bestowed with the Herculean task to act as levellers” (emphasis mine).

The Sabarimala verdict is judicial overreach. If legislating from the bench is bad enough, pontificating from it is worse.

The author is the director of the Takshashila Institution, an independent centre for research and education in public policy.