Just like the citizens of the Indian Republic, the subjects of medieval kings were not overjoyed at the prospect of their taxes being used to fund the ruling elite. Since the latter wrote most of our history, instances of struggle and resistance are rare in the historical record: except in one truly extraordinary case. In the 11th century, seeking to rein in their wealthy feudal lords, the Palas of Bengal attempted to tighten their grip on the countryside through taxation. In short order, this led to a rebellion that killed two kings, transformed Bengal’s political economy, ended the 300-year reign of the Palas, and opened the region up to the arrival of Turkic raiders. This is the story of the Kaivarta Rebellion: the most important revolt we never hear about.

Violence and taxation

I’m often asked: which period of history would I like to live in? I find this question very interesting, because the unspoken assumption is that I would be living in a royal court. But throughout time and space, the royal court was a space of unimaginable luxury, sustained by the extraction of resources from territories under military and ideological domination.

The average Indian, for most of history, lived in tough agrarian circumstances. It was not a land of milk and honey, though, of course, court-commissioned texts droned on endlessly on the quaintness of village life, how kings brought endless prosperity to their subjects, and so on. Examples of the former can be seen in the Gathasattasai (a 2nd century CE Deccan compilation of Prakrit court poetry), and of the latter in any royal inscription of the medieval period. If one were to take these claims literally, as some Twitter users tend to do, one might think that premodern South Asia miraculously suffered none of the challenges of the rest of the world; that peasants and tenant farmers were always delighted to pay tax, donate to temples, give their labour to local strongmen or adhere to rules imposed on them by kings.

But once in a while, something slips through the cracks. While it is possible to find examples throughout South Asia, here’s one inscription I’ve come across from the medieval Deccan. Dating to 1230 CE, during the reign of Narasimha II of the Hoysala dynasty of South Karnataka, it records the death of one Marayaperaya, son of Harimara Gowda of Haltore village. Narasimha II had ordered the village granted to Brahmins, to which the peasant landholders of Haltore had initially agreed. At some point, the peasants realised that this would mean the loss of their property and refused to uphold the agreement. The king’s cavalry then attacked the village, killed the men, plundered their homes, and “unloosed the waists of women”, referring to mass rape. The surviving villagers had to submit to royal authority but quietly made gifts to the families of the dead.

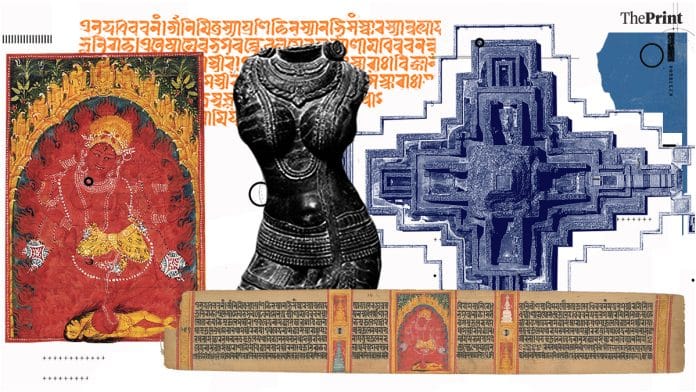

The residents of Haltore cannot have known it, but less than a century earlier in Bengal, a much larger peasant uprising had actually forced a king to come to terms. In the late 11th century, like Hoysala Narasimha II, King Mahipala II of the Pala dynasty sought to settle Brahmin officials in his core territories. It was a necessary move from his perspective. When the Pala dynasty had first established its power throughout Bengal and Bihar in the 8th century CE, it had made colossal endowments to Buddhist super-monasteries such as the Great Vihara at Paharpur, which dominated its home territory of Varendra/ Pundravardhana, present-day northern Bangladesh. These religious institutions waxed mighty as Pala vassals used them for pious tax evasion. These vassals generally owned lands in Varendra. By donating them to monasteries, they deprived the Pala State of crucial revenues while accruing religious merit for themselves.

In Characteristics of Kaivarta Rebellion Delineated from the Rāmacarita, historian Ryosuke Furui shows how the Palas tried to solve this problem: by extending their control directly into the countryside. Highly-trained Shaivite Brahmins, who could perform both religious services and act as State officials, were granted control of villages. Vassal lords were stopped from making tax-free donations. Land taxes were assessed in currency, and extensive surveys were conducted. It was a systematic, top-down attempt at medieval centralisation. But it was too much and had come too late. The spark of rebellion was lit.

Also read: Shaivite rivals were not Vaishnavites, but tantric Buddhists in medieval era

The Kaivarta rebellion

The leaders of the ensuing uprising were not, however, peasants. Instead, Divya and Bhima, two aristocrats descended from boatmen (kaivartas), spearheaded a revolt of the landed elite of Varendra—who were obviously discomfited by Pala attempts to tax them effectively. They were also supported quietly by cultivators. Mahipala II responded with overconfidence. According to the Ramacharitam of Sandhyakaranandin, he was surrounded and killed in battle. His brother Ramapala fled to the outer territories of the Palas in eastern Bihar and western Bengal. These regions were ruled by equally powerful vassals. As Furui notes, they are described as the appropriators of Brahmin settlements and of entire countries. Among them were the Rashtrakutas of Anga, Ramapala’s maternal relations, a branch of the famous (but by then extinct) imperial Rashtrakutas of the Deccan.

With even more extravagant promises of land and massive bribes of gold, Ramapala convinced his remaining vassals to fight back the Kaivarta rebels. On a fleet of boats, an advance strike force alighted in Varendra, where Bhima had begun land reforms of his own. He was defeated but escaped captivity. At this point, a massive popular uprising swelled his armies: the people of Varendra, the home territory of the Palas, did not want a Pala restoration, with the taxation and control that came with it. Bhima raised a new army of cultivators, but they were practically naked, poorly trained, and even (according to the Ramacharitam) rode buffaloes into battle. The royal forces routed them without mercy, capturing Bhima and his family. He was forced to watch them all executed before his own death.

The Kaivarta rebellion was crushed but had led to irrevocable change. For generations after, the Palas were unable to restore control in Varendra, as property records had been destroyed. And they had given away far too much to loyal vassals, all of whom had ambitions of their own. By 1165, they had been driven away in ignominy. By then, Turkic horse traders had established networks deep into the Gangetic Plains, and Turkic power was on the ascendant in the northwest. In the chaos that would ensue in subsequent decades, the Kaivartas were forgotten. But they survive today as a faint reminder: the medieval world was not a utopia, nor was it one of complete and benevolent royal domination.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)