The recent round of assembly elections in India has highlighted the growing clout of the female voter. For example, the Ladli Behna Yojana figured prominently in assessments of the BJP’s remarkable victory in Madhya Pradesh, where the party bucked what initially seemed like an insurmountable anti-incumbency sentiment.

Against this background, we conducted a study of women-oriented welfare programmes currently offered by state governments in India (Union territories are excluded from the analysis). Although a substantial body of academic research has looked at the economics of specific women-oriented welfare schemes, much less is known about the aggregate nature of the welfare state in terms of its orientation toward women. One question that arises is: Do Indian states focus on particular policy areas?

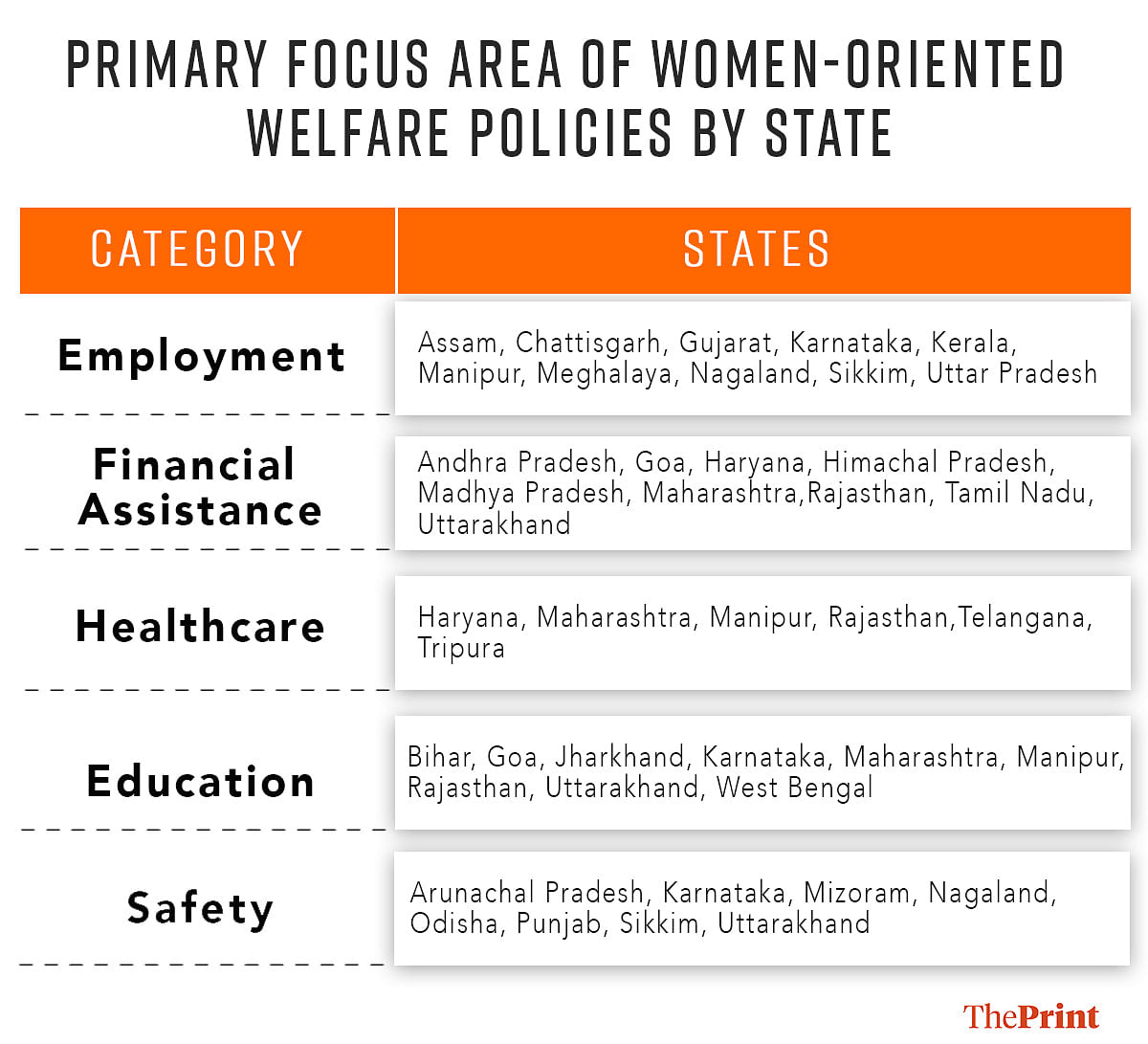

What states primarily focus on

Given that research in this area is at a very early stage, we attempted a very simple analysis by using publicly available information put out by departments of health and family welfare and organised them into categories to look for patterns.

Specifically, we classified these programmes into five categories based on their objectives and associated conditionalities for beneficiaries: employment, financial assistance, healthcare, education, and safety. A programme was considered if its focus was on women. In cases where an initiative targeted some or all of these objectives jointly, we counted it under each of the relevant categories. The coding for the project was completed in June 2023, so schemes adopted thereafter do not figure in our analysis.

Next, we identified the primary focus area of welfare policies in each state, which is basically the category with the highest programme count. For example, Madhya Pradesh had six welfare programmes for women. Out of these, we counted one under employment (Jeevan Shakti Yojana), three under financial assistance (Mukhyamantri Kanya Vivah Yojana, Mukhya Mantri Mahila Kosh, Ladli Laxmi Yojana), two under healthcare (Prerna Yojana, Ladli Laxmi Yojana), two under education (Ladli Laxmi Yojana, Gaon ki Beti Yojana), and one under safety (Ladli Laxmi Yojana). Therefore, in the case of this state, we coded financial assistance as the primary focus area. In cases where more than one category had the highest programme count, each category was coded as a primary focus area.

Table 1 shows the results of this simple counting exercise. What do the numbers tell us? Employment was the primary focus area in the largest number of states (10 out of 28), followed by financial assistance and education (9 out of 28), and then safety (8 out of 28). Healthcare was the primary focus area in the fewest number of states (6 out of 28).

Also read: Ladli Behna Yojana helped BJP in Madhya Pradesh—but points to failure of double engine…

Which factor guides the states

Having established these basic patterns, the final stage of our analysis involved using a simple machine learning tool, the classification tree, to uncover the potential determinants of these patterns. Specifically, we use four predictor variables: per capita net state domestic product measured in 2022, female literacy rates as of 2017, number of crimes committed against women as calculated in 2021, and the BJP’s statewide vote share in the 2019 Lok Sabha election. We used the machine learning approach for this exercise due to data limitations, which prevent us from “testing hypotheses” in the conventional sense. We dropped healthcare from our analysis at this stage since so few states opted for it as the primary focus area.

The results are instructive. The BJP’s voteshare predicted states’ focus on financial assistance very well. The classification tree model predicted that states where the BJP’s vote share was greater than 52 per cent would opt for financial assistance as the primary focus area. Note that Madhya Pradesh falls in this category. The misclassification rate for this prediction was 18 per cent — only five out of the 28 cases were misclassified using this rule.

The BJP’s voteshare was also the best predictor of states’ choice of education as the primary focus area. The classification tree model predicted that states where the BJP’s vote share was between 22 per cent and 55 per cent would opt for education. The misclassification rate for this prediction was 25 per cent — seven out of the 28 cases were incorrectly classified.

Female literacy turned out to be the best predictor of states’ choice of employment as the primary focus area. The model predicted that states where female literacy was between 67 per cent and 77 per cent would opt for employment. The misclassification rate for this prediction was 25 per cent — seven out of the 28 cases were misclassified.

Finally, per capita income was the best predictor of the choice of safety. The classification tree model predicted that states in which per-capita income was between Rs 79,000 and Rs 1,17,000 would opt for safety as the primary focus area. The misclassification rate for this prediction was 18 per cent — only five out of the 28 cases were misclassified using this classification rule.

Speaking to a broader debate

To summarise, two interesting aspects of state-level women-oriented welfare policies seem to stand out. First, except in the case of safety, per capita income does not predict policy orientation very well. Second, social conservatism consistently seemed to be the best predictor. The more pro-BJP the state or the lower its female literacy rate, the greater the focus on policies that help women but keep them at home – through financial assistance, for example. Conversely, the less pro-BJP the state or the higher its female literacy rate, the greater the focus on policies that help women and keep them away from home – through employment and education.

Our findings speak to an ongoing debate within Indian feminism between those who equate women’s empowerment with their labour force participation and mobility and those who argue in favour of taking women’s culturally grounded preferences seriously, which may require, if women so desire, less ambitious policy interventions. The Ladli Behna Yojana, for example, essentially monetises a portion of the unpaid labour that women do in their households without affecting opportunities for work and mobility. We are sympathetic to both sides in this debate because they are ultimately grounded in genuine concerns for women’s welfare. Having said that, we also recognise that the electoral success of direct cash transfer programmes like Ladli Behna Yojana may simply reflect the female voter’s disappointing experience with more ambitious conditional cash transfer programmes rather than some ingrained preference for staying at home.

We offer these observations as reflections at best. The data we use has clear drawbacks. For example, employment is coded as Kerala’s current focus area, even though every student of social policy in India knows that Kerala already has among the best education and healthcare facilities in the country. The data cannot capture these nuances. We invite scholars and civil society to carry out further investigations on these lines. The stakes are high.

Subhasish Ray is Professor and Associate Dean at the Jindal School of Government & Public Policy, O.P. Jindal Global University, Haryana; and an editor for the Journal of Genocide Research. He tweets @subhasish_ray75. Aakanksha Majumder is a Masters Student in Economics at the Jindal School of Government & Public Policy. Views are personal.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)