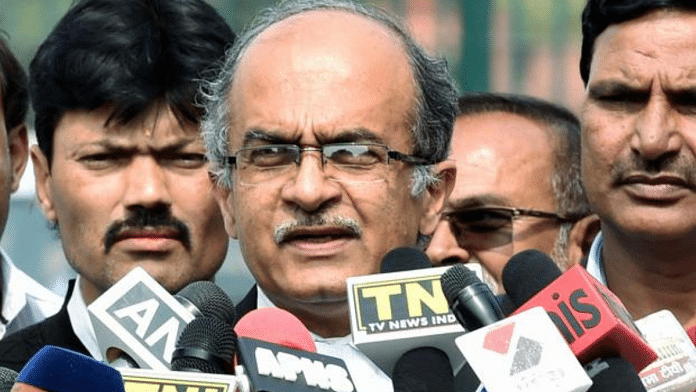

A closure or a burial? I asked myself as I heard about the Supreme Court deciding to drop the 13-year-old contempt case against Prashant Bhushan. No doubt, the order came as a welcome relief. It was a clear and happy signal—in stark contrast to the summer of 2020—that the honourable judges do not wish to be seen to be going after the whistleblowers. This augurs well, not just for the new Chief Justice but also the reputation of the Supreme Court.

At the same time, I was sad that the court missed a historic opportunity to deliberate on a matter that has been brushed under the carpet for well over a decade. The closing of this case means that some of the most explosive affidavits filed in the apex court would now remain unexamined, virtually sealed. It is shocking that these affidavits pertained to the alleged “corruption” of the top judges of the apex court. There is no other forum where these serious charges could be examined and adjudicated. Even that single forum has been closed now.

When the Supreme Court revived this case in 2020, I welcomed the move in these columns. For, the apex court’s reluctance to take up this matter had given a mistaken impression that these affidavits were too ‘hot’ for the court to handle. I had hoped that the Court’s controversial move to suddenly revive this case would get it to confront and adjudicate some inconvenient questions. I had made a plea for a “full and fair” trial that should be carried out in an open court, ideally a bench of five senior-most judges, allowing for adequate time for presentation and examination of evidence. The Supreme Court’s decision to drop the charges without getting into the facts of the case has closed this possibility.

A long, strange life

To refresh everyone’s memory: We are not talking here about the famous case involving Prashant Bhushan’s tweets regarding then-CJI S.A. Bobde’s motorbike. That case ended on the last day of Justice Arun Mishra’s tenure with a fine of Rs 1. During the same period, the Court had suddenly decided to reopen another old case of contempt of court against Bhushan. This involved his interview with Tehelka magazine in 2009 where he said, “In my view, out of the last 16 to 17 Chief Justices, half have been corrupt.” This is what led to a contempt of court case against Prashant Bhushan and Tarun Tejpal, then-editor of Tehelka.

The case had a strange life. It was filed in 2009 by Harish Salve acting as amicus curiae. But it was put in cold storage once Prashant Bhushan filed three affidavits with detailed material to substantiate his statement. It was listed and shelved again in 2012. And then it was listed again in 2020 along with the other contempt case and assigned to the same bench of Justice Arun Mishra. When it came up for hearing, Tarun Tejpal tendered an unconditional apology. But Bhushan only offered this explanation: “In my interview to Tehelka in 2009, I have used the word corruption in a wide sense meaning lack of propriety. I did not mean only financial corruption or deriving any pecuniary advantage. If what I have said caused hurt to any of them or to their families in any way, I regret the same.” The bench rejected Prashant Bhushan’s explanation and posted it for further hearing so as to determine “whether the statement made as to Corruption, would, per se, amount to Contempt of Court.” In simple English, in a country where the Constitution and a law provide for inquiry into possible misconduct of a judge of the Supreme Court, the Court wanted to find out whether the very mention of “corruption”, even if true, would constitute contempt of the court!

Thankfully, when the case was taken up after a gap of two years by another bench comprising Justices Indira Banerjee, Surya Kant, and M.M. Sundresh, the court did not follow up on this extraordinary suggestion. According to Live Law, “Senior Advocate Kamini Jaiswal appearing for Bhushan submitted that he has given an explanation for his statement. Senior Advocate Kapil Sibal, appearing for Tarun Tejpal, the editor of Tehelka Magazine, submitted that he has apologized. “In view of the explanation/apologies made by the contemnors, we don’t deem it necessary to continue matter”, the bench recorded in the order.”

Also read: What is an apology? Prashant Bhushan’s contempt case reveals true meaning of the word

What the affidavits said

Here is a sample of the rather damning questions posed by the affidavits — with reams of documentary evidence to support these claims — concerning eight of the previous 18 Chief Justices of India in the year 2009. Since we are interested not in the individuals (many of who are no more) but in the institution, I present the main points without the names of the Justices concerned.

CJI 1: Was his accepting post-retirement political office from a party not linked to his whitewashing the role of the ruling party’s leaders in a crucial inquiry commission report that he headed?

CJI 2: Did he not use his short tenure as CJI to transfer to himself and pass a series of extraordinary orders all favouring a certain export house and its sister concern? If not, why was the Court forced to review and reverse these orders in open court once he ceased to be the CJI?

CJI 3: Did he not, while being the CJI, purchase a plot and build a palatial house in an area where all construction was banned by orders of the Supreme Court? Were these orders not diluted during his tenure? Did he not become the lifetime chairman of a trust, which he had instituted, and awarded money to, when he was the CJI?

CJI 4: Did his two daughters not receive a house plot each from the discretionary quota of a chief minister on the same day that he dismissed a serious case against that very CM? Did he not, as a judge of the Supreme Court, attempt to hear cases that involved clear conflict of interest?

CJI 5: Did he not, as the chief justice of a high court, pass orders favouring a litigant after receiving a plot of land from that very person? Did he not, as chief justice of the high court, file a false affidavit to secure an underpriced plot of land from the government?

CJI 6: Did his orders for sealing commercial property in a metro not benefit his sons who, working from the CJI’s official residence, entered into profitable deals with shopping malls and commercial complexes? Were his sons not allotted huge commercial plots by a state government?

CJI 7: How come his daughters, son-in-law, brother, and one of his aids acquire vast real estate property, enumerated in an expose, disproportionate to their known sources of income after he became Judge and CJI?

CJI 8: Did he not pass orders granting a lucrative lease to a certain company despite the damning report against the project by the Environment Expert Committee appointed by the court itself? Why did he not reveal, at the beginning of the hearing, that he himself owned shares in this company?

I am not suggesting that these allegations were the final truth of the matter. Let us assume that these allegations were untrue, perhaps even motivated. Even then, when such grave allegations are made in the public domain and reiterated in a sworn affidavit to the highest court, backed by dozens of appendices with legal records, should we not expect the court to set up an impartial inquiry to set any misgiving at rest? Let us also assume that even if these allegations of misconduct were true, the judicial conduct of the concerned judges was not influenced by any of these externalities. Even then, would it not help to look into these cases to come up with guidelines on conflict of interest and financial disclosures? And just in case there was any element of truth in these allegations, would a full and fair hearing not have helped the process of judicial accountability and reform?

Finally, Prashant Bhushan had raised a bigger constitutional question, filed in a separate affidavit in 2020, not connected to any one of these judges: If a true statement scandalises the judiciary, is it a contempt of court? Does a bonafide opinion, proven true or not, amount to contempt of court?

In suddenly dropping the case that the court kept alive for well over a decade, the Supreme Court has buried these difficult questions. I am a friend of Prashant Bhushan, but I am disappointed that the court did not try him for contempt of court.

Yogendra Yadav is among the founders of Jai Kisan Andolan and Swaraj India. Views are personal.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)