It’s punishment time in Madhya Pradesh’ Gwalior district. To deal with people breaking lockdown rules and not wearing masks even as coronavirus cases increase around the country, the Gwalior administration has come up with a very Indian parent-esque solution.

Anyone found to be breaking Covid-19 preventive guidelines will be forced to work in hospitals or at police check-posts for three days, district authorities have ruled, adding to the list of punishments officials all over India have resorted to throughout the lockdown period — from raining lathis to making people do sit-ups.

But do punishments work? Indian parents have long been punishing their children for the smallest offences without much success. Psychotherapists have claimed that strict parents in all likelihood turn their children into ‘very skilled and effective liars’. Studies have shown that uber-strict parents are more likely to raise children who engage in substance abuse, and/or stealing and hurting other people.

More and more parents who act like a surveillance system fitted into their kids’ lives want an update on everything — from what they eat and whom they meet to where they go and things they do socially — and unintentionally end up convincing their children that every small decision has to be run past them.

This sense of being in control of an individual’s life is similarly witnessed in India’s administrative system, where every police officer or local official assumes the role of a parent tasked with ‘disciplining’ the average citizen. And the lockdown period has been a model example of this overbearing culture.

Also read: Spread awareness instead of putting people in jail, says Allahabad HC on lockdown FIRs

The irony of punishments

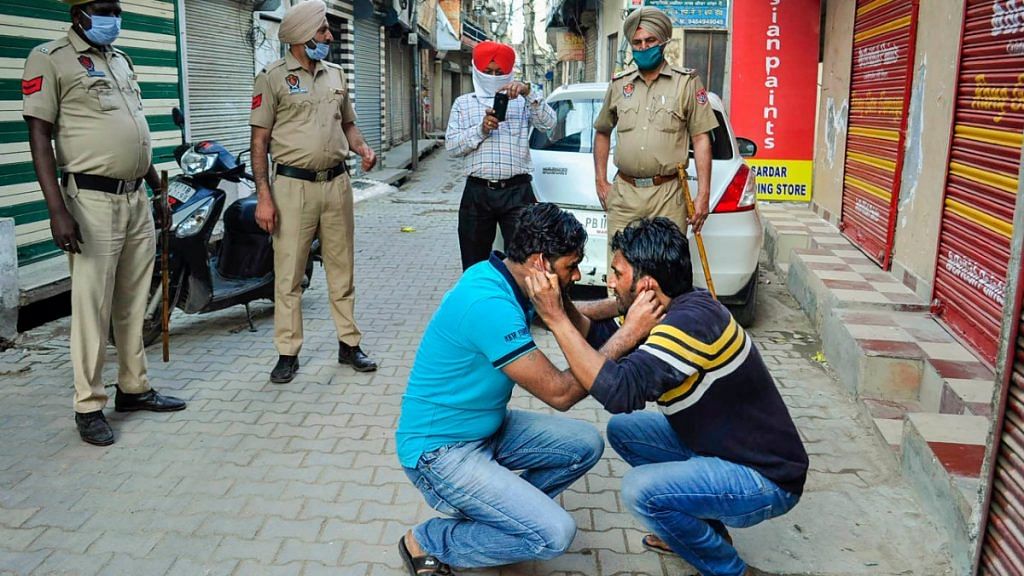

The coronavirus pandemic brought an unprecedented crisis before India’s administrative machinery with social distancing and wearing of masks becoming basic ground rules. But when a rather hasty lockdown came calling, Indian citizens were left struggling between avoiding a virus and dealing with a police force that was in no mood to show mercy. The police had a field day humiliating and lathi-charging any citizen who was breaking the lockdown. In fact, one police officer in Telangana went to the extent of slapping a woman, a post-graduate doctor, and questioning her for being out so late at night.

At other times, officers, such as those in Jharkhand, made people do ‘sit-ups’ for violating the rules. Yes, the same uthak-baithak employed by school teachers, which instead of being a corrective measure, end up being a method to humiliate students. Mostly, though, police beat up people, including those merely out buying essential goods.

The decision taken by authorities in Gwalior to reinstate the importance of Covid-19 guidelines misses the point by a mile. Doesn’t forcing citizens to work in hospitals or be on guard duty at police check-posts expose them to the risk of contracting the coronavirus? A ‘punishment’ for breaking a rule meant to save them from the virus takes them closer to the possibility of contracting it.

Also read: Stop cheering police brutality. Citizens like Jayaraj and Bennix pay the price

The administrative-parent

There is a larger trend in Indian punishment at play here. Indians love to punish those they ‘command’ with such impunity and blindness that they end up perpetuating the very same thing they aimed to prevent. Just like Indian parents, where enforcing strictness only makes the children lie more.

Authorities in their relentless pursuit to maintain law and order end up infantilising their citizens. People must be allowed to believe that they are upstanding citizens and following health guidelines is their responsibility. Constant reminders through public announcements in localities should be practised. Instances of infraction should only be dealt with further exhortations to follow the rule — not by raining lathis.

A better, more effective way is to order shopkeepers to refuse service to anyone not wearing a mask. Not only will that achieve the purpose but it will also put the responsibility of upholding rules and regulations with highest regards on the citizens.

The ways in which the lockdown has been imposed in India demand a serious reconsideration of how the authorities respond to a crisis and treat their own people.

Views are personal.