Three hours of torrential rain inundated the walled city of Jaipur last week. Low-lying areas were flooded and landslides barged into people’s homes. Not just the living, even a 2,300-year-old mummy called Tutu resting in the iconic Albert Hall museum had to be rescued. Ancient records and artefacts were at the mercy of the rain. Three people died in the city.

But the real problem was not the rain. The regal city of Jaipur has been stuck in history — and so has its drainage system. Construction of modern plans and drainage systems has been stalled for more than a decade now. In 2016, the Jaipur Development Authority had prepared a master plan for the city that had been hanging in the balance since 2007 because of the lack of funds. Residents have been complaining about open potholes and live wires, while media reports flagged concerns about clogged drains and delay in cleaning them because of the coronavirus pandemic as early as May.

Jaipur is not the only one. India often forgets to take care of the drainage systems of its cities. Poor drainage had led to flooding and water-logging during the monsoons in major Indian cities this year. The most recent example being Gurugram, where failure to clean stormwater drains led to massive flooding in key underpasses on the posh Golf Course Road. Even Mumbai’s drainage systems aren’t at par with requirements, which lead to crippling floods in the Maximum City every year. The British-era systems need an overhaul, and the encroachment in catchment areas of the Mithi River has disrupted its role in drainage of stormwater. Another annual occurrence is the floods in Bihar and Assam and their devastation. Patna is again seeing the Ganga surge this week.

Since the current flavour in India is to look to the Vedic past for guidance, solutions and national pride, there is one lesson Indians can draw from Harappa to fix our modern-day urban blight. Before leapfrogging into Artificial Intelligence-led smart cities of the future, we must time travel back to understand why we lost a critical link with the Indus Valley Civilisation – that of the humble stormwater drains.

If you speak to historians in Jaipur, you’ll find that India’s first planned city’s drainage systems were meticulously laid out, and encroachment upon waterways, and disrespect for these systems while undertaking new development projects have contributed to the current water clogging problems.

The other problem is that in recent years, rainfall is also concentrated to just a few days instead of being spread through the entire monsoon season – bringing Indian cities to their knees. A combination of climate change mitigation and paying attention to history will go a long way.

Also read: 2,300-yr-old mummy in Jaipur’s Albert Hall Museum taken out of box to rescue it from rains

The drainage systems

Historian Rima Hooja, director of the Maharaja Sawai Man Singh II Museum at Jaipur’s City Palace, cites a 1726 report by one Anandiram available in the Jodhpur Oriental Research Institute library that documents the planned structures.

After much deliberation in the 18th century, Hooja says, a canal was laid out to bring water from the Jhotwara river to the Choti Chaupar (small square), which is in the middle of the walled city and used to have a bawri (typical bawris are step wells, this was more of a water tank or kund) where water was stored for residents’ daily needs. There were similar bawris in Badi Chaupar and Ramganj, which lie to the south-right and south-left of the Choti Chaupar, respectively, forming sort of a T. These two centuries-old bawris, along with well-connected tunnels and artefacts, were unearthed during the Metro construction in 2016.

All the excess water would then go to Talkatora, Rajamal ka Talab, or the Mansagar lake (Jal Mahal lake), serving markets, palaces and gardens of Jaipur along its path.

Introduction of pipe water systems had started in the late 1800s, and terracotta pipe systems laid out. In the 1920s, the bawris were replaced with fountains on the squares. The Rajamal ka Talab doesn’t exist anymore, and a society complex has since been developed in the marshy land.

In 1903, the Ramgarh dam, roughly 45 kilometres from Jaipur, was built by Madho Singh II. It started supplying water to the city in 1931.

The Ramgarh lake now sits dry, which once had so much water that the 1982 Asian Games rowing championships were held there. Now, even after so much rain, the water doesn’t go beyond the two-feet mark. “The dam was built when the city’s population was about 1 lakh, keeping in mind the needs of 10 lakh people. It used to have 65 feet water at one point, but now it’s completely dry, and doesn’t fill up no matter how hard it rains. It is because of the constructions that happened in its catchment area,” a local BJP leader told ThePrint.

Pankaj Sharma, former chief curator at City Palace, says if the old systems had been working properly we wouldn’t see this level of flooding. “Jaipur’s history is very well documented, even lightning strikes at Sanganeri Gate have been recorded, but it says nothing about any problems of flooding or waterlogging before 1981, whatsoever. This goes to show just how effective old systems were,” he says. Sharma also notes the recent devastation on 14 August was just due to 2-3 hours of heavy rain. What if it had rained for 5-6 hours? The city doesn’t seem to be prepared to handle that kind of pressure.

“Drainage systems were also blocked from releasing water into Mansagar lake during its renovation,” Sharma says.

Also read: Now world truly values Jaipur: How residents thanked us for getting UNESCO Heritage tag

The 1981 floods

As the population of Jaipur grew, the meticulous planning of the old city saw was thrown out of the window, waterways were encroached upon and the drainage systems weren’t paid much attention to. In July 1981, a cloud burst led to torrential rains and floods in Jaipur, which revealed some encroachments, and ironically led to even more of them.

“During the floods in 1981, a lot of these systems, which were already partly ruined, silted away. Even then, when the water washed everything away in its wake, one could see degrees of encroachments,” Hooja says.

Reena Chaturvedi, a survivor of the 1981 floods says she saw verandahs of houses hanging on hollow foundations, and that revealed drain systems underneath the Ashok Nagar area of Jaipur. Over the years, she has seen many drains getting lost to such encroachments.

“Our ancestral home’s address was ‘near ganda nala‘ at 5 Batti on MI Road, today the nala has been replaced by a thriving Jayanti market,” Chatuvedi says.

According to a report, right after the 1981 floods, when the ‘nala’ dams were washed away, the land mafia grabbed massive chunks of the dry riverbed. Turns out, the Amanisha nala in Jaipur was a perennial river of Dravyavati. Numerous encroachments on the riverbed have since been regularised by successive governments. But projects to restore Dravyavati riverbed are underway.

Also read: A policy capping human density is what India needs for its flood-prone cities

Metro construction

The Jaipur metro construction has thrown even more light on the city’s vanishing drainage system. Jaipur-based artist Yunus Khimani was the director of the Maharaja Sawai Man Singh II Museum when he was called to examine tunnels, presumed to be ancient drainage systems, that were unearthed at Choti Chaupar in Jaipur in 2016. “I went down to inspect it, they were about five-feet tall, not big enough to be escape routes,” he told ThePrint.

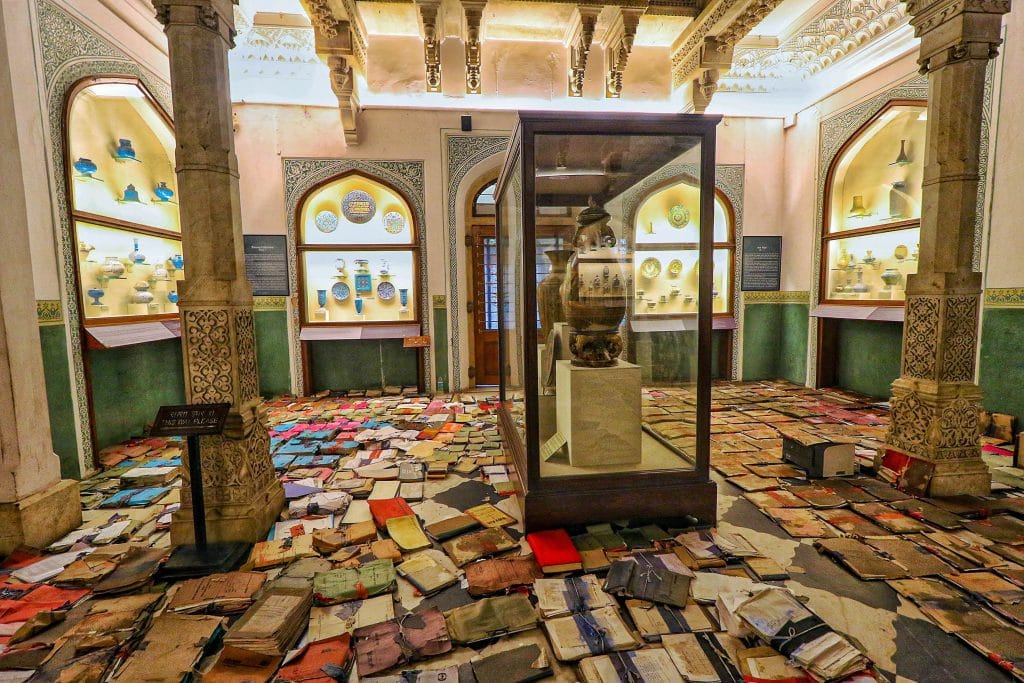

In fact, so many artefacts were unearthed during the digging for Jaipur Metro that a heritage museum connected through underground Metro tunnels is being planned so people can go and visit the old structures.

According to Pankaj Sharma, the Metro now runs parallel to these tunnels and has damaged the ancient systems to a certain extent. He says the new development projects haven’t respected the old.

The underground drainage systems are also obstructed because most shop owners in old Jaipur have constructed storage basements below their shops. “Earlier, not even a single shop had a basement, now every shop has one. The water doesn’t flow properly because of this,” Sharma adds.

Also read: Jaipur’s ‘smart voters’ complain the city is yet to catch up with them

Other factors

Hooja notes that the rising level of roads and layers of tarmac have added to the city’s water logging problems. “Roads are 3-6 feet higher now, so water seeps down to low-lying areas,” she says.

Over the years, the Aravali hills around Jaipur have also been unthinkingly cut for resources such as limestone, and unplanned settlements have cropped up in nearby areas. This resulted in rainwater coming down with full force into houses and engulfing cars in mud last week. “They’ve cut trees incessantly. So, mud and water enter houses in areas that must have once been waterways, and damage these structures,” Subodh G. Rajguru, a civil engineer in Jaipur, says. Just look at the wrath with which water came down from the Aravalis:

#jaipurrain | Water coming down from hills damages houses on Delhi road on the outskirt of Jaipur. pic.twitter.com/qZeABvH42R

— TOI Jaipur (@TOIJaipurNews) August 14, 2020

At Ram Niwas Bagh, overlooking the city is Maharaja Sawai Man Singh II, who, the story goes, had wished his statue to be installed there so that Jaipur could always be safe under his protective gaze.

Jaipur is a well-thought-out, laid-out and planned city whose founders paid attention to each aspect during its construction, and the stories of architectural marvel and dexterity tell tales of a city made with love, labour and patience. Irresponsible development projects and subsequent encroachments disrespect everything its founders stood for. Wonder what Man Singh feels today as he looks over the city, helplessly.

Views are personal.