All that India’s poor need is food — do waqt ki roti. But, the poor didn’t decide that. We decided it for them. And the latest affirmation of this benign judgement comes from the horse’s mouth — Chief Justice of India S.A. Bobde.

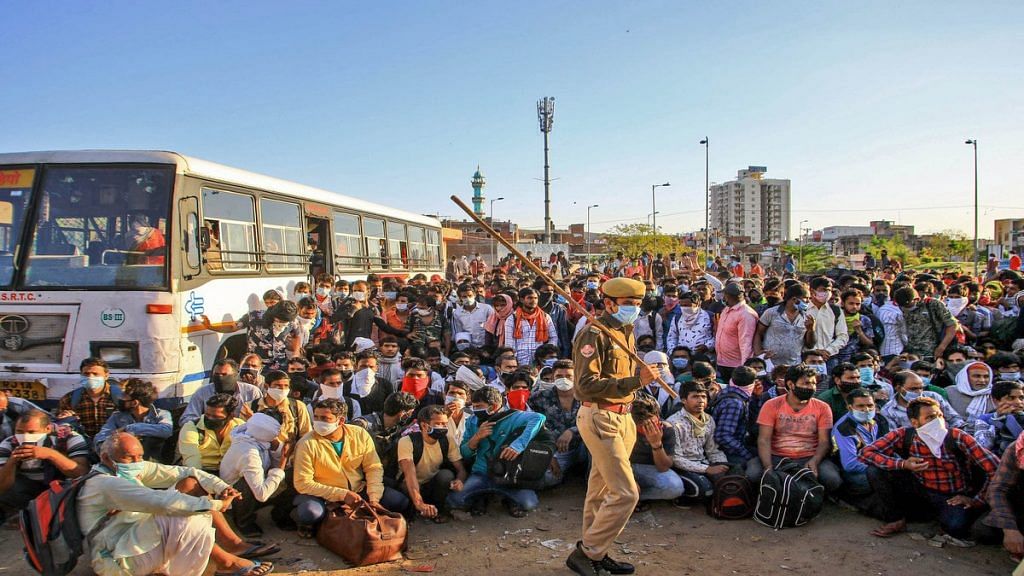

“If they are being provided meals, then why do they need money for meals?” Advocate Prashant Bhushan, pleading before a CJI-led bench of the Supreme Court (SC), was told during the hearing of a PIL. The PIL sought a directive from the SC to the Narendra Modi government to give money to migrant labourers and daily-wage workers left jobless since the coronavirus-induced lockdown.

Also read: Covid-19 can push 40 crore informal sector workers in India deeper into poverty: ILO

Setting limits for the poor

The limits on expectations fixed for the poor are also restrictions that the Indian society has imposed on itself. The act of feeding is a conscience cleaner, a hand wash that also kills the hopes of the poor wanting anything more than food. These are old models of charity.

When the government and society turn off all thoughts of doing anything more, it just becomes an act of drawing comfort from a plate of meal kept before the poor. What about the tough task of ensuring they have jobs to return to?

The fact is, deep down, those in power know that these migrant labourers need much more than just food, just like they do. For starters: healthcare, compensation for sudden loss of jobs, their due salaries and a guarantee that they will find jobs when the pandemic is over would go a long way in providing true justice.

Equating food distribution with charity and justice isn’t a product of the lockdown. It can exist beyond such crises.

If the government-provided ‘food’ is a substitute for the wage, then it’s not just the people who lost jobs that need to be fed but everyone who depends on their income — the labourer’s spouse, their kids, their parents.

If a fed stomach is the ultimate criterion, then governments and institutions must immediately stop including the poorest of the poor in their big, collective dreams for society — for 1.3 billion Indians. With only two meals a day the poor cannot contribute to your fanciful dreams.

Also read: Unemployment in March highest since September 2016, CMIE data shows fallout of Covid-19

Food philanthropy

In a country like India, where about 40 per cent of the total food produced in a year is wasted even as close to 20 crore people sleep hungry, the attitude of providing food to the poor becomes a major philanthropic act. But is that what drives the common Indian?

This philanthropy too, it seems, is driven by the sight of thousands of homeless migrants sitting by the roadside waiting for food. Food delivery startup Zomato has partnered with the NGO Feeding India after the lockdown. Religious tenets of serving the poor too drive this philanthropy. What else explains community kitchens at gurdwaras, mosques, and temples?

But what about the CEO clubs in cities like Gurgaon or leftover food at lavish weddings and banquets? Is it only the melting heart at the sight of a poor that makes everyone in India want to feed the needy?

Giving food comes easy to most Indians because society has established that it is the only thing a poor needs at the end of the day. That is why people argue against extending monetary support to the poor. A poor woman carrying her baby cannot expect to receive money as aid because ‘who knows what sort of racket she might be running?’ ‘Buy them food, if you really must help them.’

Also read: Why fixing unorganised sector can be Modi’s biggest Covid-19 economic challenge

The (mis)allocation of wealth

The ongoing coronavirus pandemic is estimated to put 40 crore Indians at the risk of falling deeper into poverty. If not for India’s ability and desire to feed them, it would have been a cause for worry.

It helps governments that all they have to ensure — without much accountability in case of failure — is that the poor somehow have access to food. It keeps their responsibility to the bare minimum. And it helps them focus on building smart cities (with poor citizens), funding statues and monuments, and keeping the rich happy by waiving loans.

If food was indeed all that anyone needed, then people losing sleep over money would have applied this principle to become more content in their lives. If governments and institutions like our courts really thought a fed stomach was the end goal, then the political class wouldn’t have drowned itself in free facilities or judges wouldn’t have quietly accepted a 200 per cent pay hike.

At the least, especially in a charitable society like ours, no human being would have starved to death.

The established order under which wealth gets allocated ensures that the luxury and comfort of those in power, the rich, and everyone else high up in the pecking order is taken care of first. The leftover goes to the poor.

Food is not the end of your responsibility. And don’t gloat about your charity just because you have taken away people’s dreams and desires.

Views are personal.