No, she isn’t India’s Frida Kahlo, she is India’s Amrita Sher-Gil. To consider her a lite version of any other artist would be to ignore one of the greatest women India has seen. And a proposed biopic by Mira Nair — who else would do her justice — shows we still haven’t paid our dues to one of the pioneers of modern Indian art.

Everyone, from Jawaharlal Nehru to Mulk Raj Anand, was Amrita’s fan. It is a different matter that most of Nehru and Amrita’s letters were burnt by her parents. She was bisexual, snarky, humorous — (she famously called Khushwant Singh’s child ugly) — and almost always knew what she wanted. Even in her 20s (sadly the last decade of her life), she knew who she was and her worth. It is no mean task to openly say, “Europe belongs to Picasso, Matisse, Braque and many others. India belongs only to me,” when the likes of Nandalal Bose, Jamini Roy and Abanindranath Tagore are painting at the same time as you.

If Mira Nair’s film on Amrita Sher-Gil isn’t as complex as the artist herself, or doesn’t make you both love and question the woman, then it won’t do justice to a personality that had many shades. An artist was born, found her own artistic voice and died, is not Amrita’s tale. And the film can’t take away from her — it would throw her universe off balance.

There are five things no film on her can ignore — no matter how India wants women to behave and see, even in 2020. These are Amrita Sher-Gil’s atheism, audacious feminism, untethered sexuality, art, and possible abortions.

Remember Salma Hayek’s Frida (2002)? That’s what Amrita deserves too — a montage of love, life, chaos, art. Played by an actor who understands her — you can’t play Amrita by script. Directed by a woman director who is the master of her art — Mira Nair has checked that off. Written about someone who talks to her through the script.

Like every brilliant spark — Amrita Sher-Gil died at 28 in Lahore, leaving behind a legacy in Indian Modern art and caskets of enigma. And to think that even after 79 years of her death in 1941, the same year that Rabindranath Tagore died, we are only getting a proper film now.

When I first saw Sher-Gil’s art at the National Gallery of Modern Art in Delhi — I was stunned. I had read and read about her, but here she was completely new. She was my age when she painted these canvases, and yet it was bold, steady and had conviction. You instantly want to know her — the canvases aren’t enough. So, if the film doesn’t leave you wanting more of Amrita, then it is an injustice.

And any film on her must remember her distaste for biographies. “They ring false…,” Sher-Gil had said while accusing them of “pomposity” and “exhibitionism” in a letter to Nehru.

Also read: ‘Gorgeous drama but flat dialogue’ — Mira Nair’s ‘A Suitable Boy’ opens to mixed reactions

No god for Amrita

Born to Punjabi Umrao Singh Sher-Gil and Hungarian Marie Antoinette Gottesmann in 1913, Amrita was the first of two daughters. It is this diverse heritage that would define Amrita, her art, and views throughout her life — always on the threshold between Europe and India.

She was constantly exploring her identity, even as a child. She fit no mould and was a precocious teenager. After the family moved from Hungary to India, Amrita got expelled from a Shimla boarding school because she said she was an atheist. She was not even 16 by then. “She disapproved of compulsory church attendance and told her father that she was an atheist. The mother superior came to know about her views and expelled her,” wrote Vivan Sundaram, her nephew and artist.

Amrita was modern and traditional — and had no qualms about it. And neither should we. Atheism is still taboo in India, but here she was, vowing for it almost a century ago.

Also read: Lipstick under burkha to lipstick under mask — Why Indian women won’t stop now

It’s okay to have sex, with many others

Religion wasn’t the only thing Amrita questioned. Her sexuality has been the centre of much talk, gossip and derision — even when she was alive.

From a very young age, when she was training in Paris, Amrita knew she was attracted to women, too. It was also the Bohemian culture of the city in the 1920s and 1930s that led her to be more open and experiment with her sexuality. It was evident in her art, the way she drew the women and men she admired, and her countless encounters with the ‘muses’.

Her mother forcing her to marry a nobleman, Yusuf Ali Khan, didn’t help either. Amrita Sher-Gil got out of that relationship with an STI and an abortion. And a closer relationship with her doctor and first cousin — Victor Egan, something her mother hated tremendously. She would go on to marry Egan but that didn’t mean she gave up sexual liaisons. As biographer Yashodhara Dalmia writes in Amrita Sher-Gil: A Life, “…Victor was very tolerant of her sexual adventures and Amrita herself attached no importance to them.”

A concept lost on most Indians today, who still believe marriage is the pinnacle of one’s romantic life.

This shouldn’t be a difficult aspect of Amrita for Mira Nair to portray. After all, Nair’s camera has always captured Indian women, their conflicts, the turmoil inside them and the love outside, perfectly. She can capture Amrita’s quest to belong in both Europe and India, like she did with Tabu’s character Ashima Ganguli in The Namesake (2006). She can capture Amrita’s preoccupation with the downtrodden and oppressed in her art like she did with Salaam Bombay! (1988). And she can capture the power dynamics of Amrita’s various international romantic liaisons, like she did with Mississippi Masala (1991).

Also read: Khudiram Bose never got his due as a freedom fighter, ZEE5 just made it worse

DIY artist

“I will enjoy my beauty because it is given for a short time and joy is a short-lived thing,” Amrita Sher-Gil wrote in a letter in 1931.

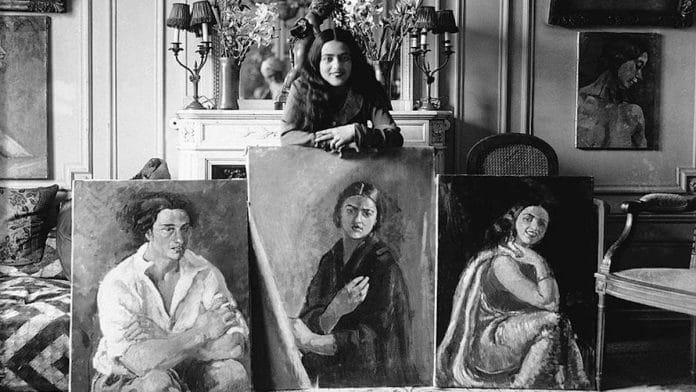

And it shows in her self-portraits. Spools have been written about Sher-Gil’s art, her journey to find her own modern ‘Indian’ style, her earthy colours, her travels across the country studying people and history, and the respect with which she treated her subjects. We will not go into that. Instead, we will take a look at her self-portraits.

Whether it is Self Portraits (7) where Amrita painted herself in Paris, young, exuberant, laughing or Self-Portrait as a Tahitian where she paints herself nude waist-up in a sombre mood, here was a woman who could look at herself, document her body, not through a man’s voyeuristic gaze, but through her own steady brush. We still struggle with body issues, and I am sure she did too, but she was honest about her flesh.

I don’t know if Amrita Sher-Gil ever called herself a feminist, but she was one — an inspiration to most women. You can be whoever you are (even in the India of 1920s and 30s).

She wore saris in Hungary, laughed without self-censorship, fought with her mother about the man she loved, drank beer from Khushwant Singh’s fridge, pleasured herself, and created her own unique painting style.

“She found such a singular voice — a voice that remains modern and iconoclastic — and a vision that taught me how to see,” Mira Nair told Financial Times, hoping she could start filming the biopic next year.

In life as in death, Sher-Gil stirred up controversy. Did she die because she had unsavoury pakodas from a friend’s house or because she underwent a bad abortion— we don’t know. What we do know is that she passed away in Lahore, the very city where she was conceived, leaving an unfinished painting of buffaloes.

But she can come alive again, thanks to Mira Nair. And India can be Amrita’s once again.

Views are personal.

India might be Amrita’s but Amrita will never be India’s. We didn’t change because we didn’t wish to. We celebrate our traditionalism and thought process. Amrita will always be too good for a nation like India. Wish I knew her.