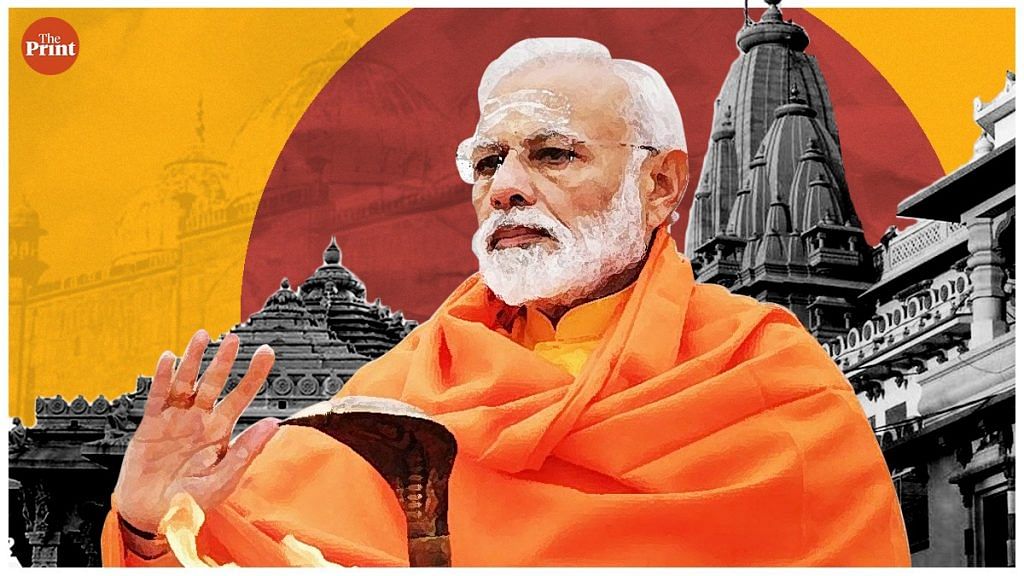

How would Prime Minister Narendra Modi like his reign to be remembered by posterity: A golden, cathartic era for Hindus when they finally got over their sense of victimhood; or, just another era of mixed successes and failures in their long struggle to correct the perceived historical wrongs?

We may get a clue to the answer when the Modi government submits its response in the Supreme Court to a PIL filed by Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) spokesman and lawyer Ashwini Kumar Upadhyay challenging the Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act, 1991.

The Place of Worship plug

Brought in by the P.V. Narasimha Rao government, the law prohibits conversion of the “religious character” of any place of worship—as it existed on 15 August 1947—except the Ramjanmabhoomi-Babri Masjid in Ayodhya, which was sub-judice then.

All pending suits and proceedings in courts about such conversions stood abated or terminated. The legislation also barred courts from entertaining pleas about changes in the religious character of places of worship pre-dating India’s Independence.

When a five-member Constitution bench of the Supreme Court settled the Ayodhya dispute, allotting the land for the construction of the Ram temple in 2019, it seemed to have precluded all future disputes of a similar nature by endorsing the Places of Worship Act, 1991. “The law is…a legislative instrument designed to protect the secular features of the Indian polity, which is one of the basic features of the Constitution…is a legislative intervention which preserves non-retrogression as an essential feature of our secular values,” the SC had said in its verdict.

Last Friday, a Supreme Court bench, headed by Chief Justice S.A. Bobde—who was part of the Constitution bench that delivered the Ayodhya verdict—agreed to examine the validity of the Places of Worship Act and sought the Centre’s response. It may have far-reaching implications.

Also read: Let Ayodhya Ram Mandir be a reminder: Indian ancestors died for it, up to us to rebuild

If the Supreme Court reaffirms the 1991 law, courts can’t entertain pleas about alleged pre-Independence conversions of places of worship—say, for instance, civil suits for removal of Varanasi’s Gyanvapi mosque that shares a boundary wall with the Kashi Vishwanath Temple, and of Shahi Idgah mosque adjacent to Krishna Janmasthan temple in Mathura. The Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP), which had spearheaded the Ayodhya movement, claims these mosques in Kashi and Mathura were built after demolishing temples during the Mughal period. There are also civil suits in Varanasi and Mathura courts for removal of these mosques.

If the Supreme Court invalidates the 1991 law fully or partially—to allow court proceedings in matters concerning pre-1947 conversions—it’ll have a bearing on the country’s politics, governance and landscape for decades to come.

Also read: Why Babri masjid demolition verdict is unlikely to end all temple-mosque disputes

Time for closure?

Legal hurdles posed by the 1991 legislation are, however, the least of the Modi government’s concerns. Regardless of the SC’s views on the law, the government can get Parliament to invalidate it any time it wants. After all, who will oppose if it brings an amendment bill in Parliament, saying that the Hindus want justice for historical wrongs: ‘Brahmin Hindu’ and Chandi Path-chanter Mamata Banerjee, or Arvind Kejriwal who has been reciting Hanuman Chalisa and promising Ram Rajya, or Akhilesh Yadav who is visiting temples, or Rahul Gandhi who has become a ‘janeudhari Dattatreya Brahmin’, or Naveen Patnaik who is busy renovating and beautifying temples in Odisha?

Therefore, as the government prepares its view on the validity of this law for submission in the apex court, the real issue is whether the Hindus need closure on the decades-old narrative of victimhood during the Modi era or they must keep fighting, legally and politically, until every single historical wrong is corrected. The second option may take decades and it would mean that what was started during the Modi era with the Ayodhya verdict will then have to be completed by Yogi Adityanath, Amit Shah or somebody else.

After the bhoomi pujan ceremony of the Ayodhya temple, PM Modi had said that it marked “the culmination of centuries-old penance, sacrifices and resolve”. Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) chief Mohan Bhagwat had called it “the beginning of a new India”, adding that it “brought back the sense of self-confidence, which was lacking, to make India self-reliant”. Their speeches gave the impression that they were looking at the Ram temple construction as a kind of closure on the perceived historical wrongs to the Hindus. Bhagwat had hinted as much after the SC verdict on Ayodhya: “The Sangh does not get involved in any movement. We work towards character building. In the past, the circumstances were different, resulting in the Sangh getting involved in the (Ayodhya) movement. We will once again work for character building.” The impression was further buttressed by the BJP’s silence on the Mathura and Kashi disputes, except for some solitary voices like Subramanian Swamy and Vinay Katiyar.

Also read: Babri ruling is BJP’s golden goose. Mathura, Kashi signal to erase India’s Islamic history

Legacy vs politics

It’s difficult to predict the answer to the question posed in the beginning of this article on the Modi era. There are two factors that may determine this answer: What legacy PM Modi wants to leave behind and how it figures in the promotion of the Sangh Parivar’s political and ideological agenda.

To deal with the second factor first, as I reported last September, the Sangh is already making a nuanced shift in its stand, saying that it would go by “what the samaaj (society) thinks” about Mathura and Kashi disputes.

As for political reasons, the BJP-led government may not feel obliged to defend the 1991 law in court. In 1991, the BJP had staged a walkout when the bill was taken up for consideration and passage in Parliament. Uma Bharti had then thundered in the Lok Sabha: “By maintaining the status-quo of 1947, it seems you are following a policy of appeasement. Owners of bullock carts in villages create a wound on the back of the ox and when they want their bullock-carts to move faster, they strike at the wound. Similarly, these disputes are wounds and marks of slavery on our Bharat Mata. So long as Gyanvapi continues in its present condition at Banaras and a grave remains in a temple at Pavagarh, it will remind us of the atrocities perpetrated by Aurangzeb.”

One may argue that BJP veterans like L.K. Advani and Uma Bharti have no voice in today’s BJP. But the fact is the party is still banking on Hindus’ victimhood narrative as it seeks to expand its footprint in new territories—say, in West Bengal and south India. ‘Threats to Hinduism’ is its war cry in Andhra Pradesh as it seeks to mobilise the majority community in a Christian CM-led state.

On the one side, there are political and ideological imperatives, which make it incumbent on the Modi government to disown the 1991 law in the court. But, on the other side, there is the option of ensuring PM Modi’s place in history as someone who addressed Hindus’ “pain from the past” and found them reconciliation by bringing India’s “civilisational moment” in the form of Ram Mandir bhoomi pujan, as diplomat and Shiva trilogy author Amish Tripathi told ThePrint’s Editor-in-Chief Shekhar Gupta on Off the Cuff.

PM Modi has enough time to ponder over the legacy-versus-politics question. The SC hasn’t set a timeframe for the government’s view on the 1991 law. Justice Bobde will retire next month, which would mean reconstitution of the bench to hear this matter. Going by the pace of hearings on crucial matters in the Supreme Court, the government may have adequate time to formulate its response. Ideally, there will be more clarity closer to 2024.

Views are personal.