Indira’s was a ruder socialism than her father’s. Hers was a unique socialist-populism which we call povertarianism. The Iron Lady realised, but too late, that she had erred.

It is generally accepted wisdom that the Indira Gandhi years were the pinkest in India’s economic history. Also, that her second phase (at her peak from 1971 till post-Emergency decline in 1977) was the most deeply socialist of the three, the first being 1966-71 and the third 1980-84. Some of India’s worst economic laws were enacted by her largely illegitimate Parliament during the Emergency, some even in its shameful sixth year.

Much of the stuff on her politics, creative destruction of the Congress and Emergency, her iron will and patriotism is familiar to most Indians. Her mostly shambolic (the green revolution being one bright spark) economics has gone undebated even in her centenary week.

Fresh, intriguing, and sometimes pleasant surprises have emerged lately on how her economic thinking evolved over these years. T.N. Ninan had initiated this debate with a provocative 2015 column. He had said, intriguingly, that far from reinforcing her socialist drive, Indira Gandhi had actually begun to loosen things up, or at least start some review and introspection by the end of 1974, a year before the Emergency.

Briefly, his thesis is that by this time, India was in deep economic distress. Inflation was running high, there was widespread popular disenchantment, and Indira had made her most significant economic blunder yet. Under pressure from her durbari revolutionary cabal, D.P. Dhar, P.N. Haksar, etc, she nationalised grain trade and that too in a crisis year for agriculture. It caused such anger among farmers that, for the first time in her prime ministership, she was forced to withdraw a major decision.

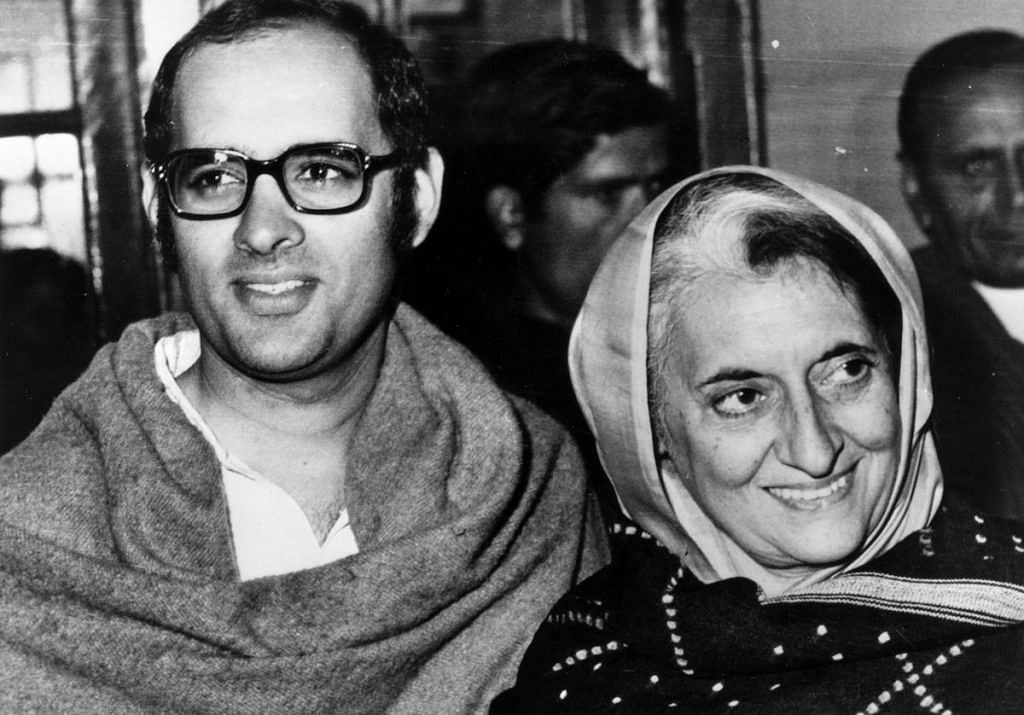

This set in motion the process of review and rethink. It was strengthened by two personalities, though one in departure and the other in arrival. In 1973, an Indian Airlines crash in New Delhi took away her steel and mines minister, and her most leftist comrade, Mohan Kumaramangalam, a former Communist Party member who had learnt more ideology at Kings College, Cambridge, than law. Second was the rise of Sanjay Gandhi who was Kumaramangalam’s opposite in economic thinking, even if you would not exactly describe him generally as a libertarian.

We journalists are not historians, scholars or astrologers. Our skills are generally limited to faithfully observing and chronicling the present, not searching the past or predicting the future. Let’s pass astrology for now, but thankfully we still have wonderful historians whose work we can rely on. You can find a great deal of wisdom and insight, for example, in Srinath Raghavan’s brilliant essay on ‘Indira Gandhi in Makers of Modern Asia’, edited by Ramachandra Guha.

Raghavan says Indira’s “socialist phase” continued till 1973. But this momentum was broken by a crisis inevitable in a post-war, populist economy. Monsoon failures and the 1973 oil shock, he reminds us, had taken our inflation rate to 33 per cent by late 1974.

This also fuelled the JP movement. Indira first resorted to a tough anti-inflation squeeze, never mind the warnings of her Left ideologues that these would annoy people. She preferred, Raghavan tells us, the advice of the “more liberal” economic advisors, led by that virtuous usual suspect, Dr Manmohan Singh. She also approached the IMF for a $935 million (a lot then) bailout, quietly allowed the rupee to depreciate, thereby improving India’s exports and reserves. Raghavan argues that 1973-74 “marked an important turning point” in her economic policy, one that remains “underappreciated”. The shift, he says, was attitudinal more than substantive, but it brought growth. During 1975-78, India grew at six per cent per year, which was twice the fabled Hindu rate.

He quotes extensively from a fascinating exchange of letters between Indira and her close advisor and cousin, B.K. Nehru, whose views on economics were more liberal than on individual liberty—he had hailed the Emergency as a “tour de force of immense courage”. Now he was telling her to replace garibi hatao with utpadan badhao (increase production). Some of Nehru’s lines are stunningly prescient, and we were repeating the same thought, even if not so succinctly, during Sonia Gandhi’s povertarian UPA 2.

Raghavan quotes a December 1974 letter from an irritable Indira reminding Nehru that “under present conditions there can be no economic growth which ignores social justice” (sounds familiar?). B.K. Nehru bravely joins that battle of ideas by asking whether “social justice [means] equality in poverty or growth in the size of the national cake which may continue to be divided in unequal portions if necessary”. He goes on to argue that “all other objectives should be subordinated to this one objective of increasing production”.

This isn’t much different from an oft-repeated lament of “equal distribution of poverty” by my economist friend Surjit Bhalla, who P. Chidambaram describes as being way to the right of Adam Smith, and which led me to the discovery of that trade-marked term, povertarianism.

But if one air crash (that killed Kumaramangalam) had broken the socialist momentum, another intervened to disrupt her reformist phase as Sanjay died in his aerobatic plane so early in her new term (23 June 1980). Indira’s will and spirit was never the same again. Her intellectual shift, however, continued.

I have it on the authority of several aides and advisors who watched her closely, including foreign service giants like Jagat Mehta and J.N. Dixit, that she felt rotten at the position India was forced to take on the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. She felt humiliated that some of the speeches by our envoys at the UN sounded more grating than those of the Cubans. She also—probably—had the sense that the Cold War was going to end, and India couldn’t afford to end up totally on the loser’s side.

There is evidence that she had begun course-correction on foreign policy as well. In the 1981 multilateral summit at Cancun, Mexico, I believe she sought out Ronald Reagan, her first contact with the US at a high level after her disastrous time with Nixon. The following year she visited Washington and a process of mending relations was well and truly under way. She seems to have realised that in the new global strategic and economic order after the Cold War, India could not carry on being at odds with the West.

By 1983, however, India’s internal security situation had deteriorated. It left little scope for further economic action. Assam was out of control in February 1983. Bhindranwale had risen, guns and all, in Punjab. What followed, is relatively better known, more recent history. She has been deservedly given a place in history as a great patriot and martyr, a champion of India’s integrity and sovereignty. Could it be that we have not yet fully appreciated her intellect and prescience on economic and foreign policies?