Perhaps no other book from ancient India has been, and continues to be, loved more by people in India and across the globe than the Panchatantra. Even those who do not know its name have been exposed to its charming stories that their mothers told them when they were children. Its fame was such that travellers and storytellers took this little gem of a book on a journey around the world. Franklin Edgerton, who attempted to reconstruct the original text from the extant versions, commented on the popularity of the Panchatantra:

“No other work of Hindu literature has played so important a part in the literature of the world as the Sanskrit story-collection [called] the Pañcatantra. Indeed, the statement has been made that no book except the Bible has enjoyed such an extensive circulation in the world as a whole. This may be—I think it probably is—an exaggeration. Yet perhaps it is easier to underestimate than to overestimate the spread of the Pañcatantra.” (Edgerton, The Pañcatantra Reconstructed, 1924, p. 4)

The prelude to this collection of stories identifies its author as Vishnusharman, an octogenarian Brahmin. He had accepted a challenge by Amarashakti, the king of Mahilaropya, to educate his three dull sons in preparation for their royal duties. This ascription is probably a literary artifice, but it shows why a book seeking to teach politics and statecraft uses the medium of animal fables. Vishnusharman thought that stories were pedagogically more suited to teach important moral and political lessons to young children. Today, I want to tell you the story of the world travels and vicissitudes of this delightful book.

The Panchatantra was probably composed around 300 CE, although this, as most ancient Indian dates, is an educated guess. What we know for sure is that it was translated into the old Iranian language of Pahlavi around 550 CE by a Persian doctor named Burzoe.

The Panchatantra’s world travels

Why did Doctor Burzoe think that his countrymen would have liked to read the Panchatantra in their own language? Perhaps they would enjoy its entertaining and instructive animal fables. Entertain and instruct appear to be the twin goal of the Panchatantra and the reason for its global popularity. How did Burzoe translate the Panchatantra? Today, we are used to scholars rendering faithfully the original in the new target language, maintaining as far as possible the original structure. The pre-modern translations of the Panchatantra—by Burzoe and his successors—were very different. They were retellings of the original, recasting it to suit the aims of the translators within the new cultural settings.

Burzoe’s Pahlavi translation was re-translated into Old Syriac around 570 CE and into Arabic around 750 CE under the title Kalilah and Dimnah derived from the names of the two jackal ministers, Karataka and Damanaka, of the lion king Pingalaka.

The Westward migration of the Panchatantra was parallel and exceeded by its spread across the Indian subcontinent. As people read and absorbed this enchanting book of animal tales, they started producing new versions and editions. We have, for example, one from Kashmir called Tantrakhyayika, often considered one of the earliest versions. Likewise, there were versions produced in the South and in Nepal. In 1199 CE, a Jain monk named Purnabhadra produced an expanded edition of the book with many more stories, and it is this version that is commonly available in modern India. A medieval recasting of the book with the title Hitopadesha, written probably in Bengal by one Narayana, became very popular. It presents itself simply as a book of fables teaching common wisdom rather than statecraft.

Also read:

Hebrew, Spanish, Latin Panchatantra

Circling back to the international travels of the Panchatantra, the Arabic translation spawned several retranslations beginning with Persian. A Hebrew translation followed in the 12th century and a Spanish one around 1251. The Hebrew version was the basis of the Latin translation in the late 13th century. This Latin rendering was the first Panchatantra version to be printed in 1480. This printed Latin version became well known throughout medieval Europe and spawned a German translation around 1480 and an Italian one by Doni published in 1552. An Englishman named Sir Thomas North translated Doni’s version into English in 1570 under the title The Moral Philosophy of Doni.

Early in the 20th century, Professor Johannes Hertel, a pioneer in Panchatantra research, recorded over 200 versions of the book in more than 50 languages. He estimated that over 30 of the languages the Panchatantra was translated into were from outside the Indian subcontinent, its reach extending from Java to Iceland.

University of Leipzig in Germany organised an international conference titled ‘Panchatantra across Disciplines and Cultures’ with 21 scholars from India and across the world in September 2012. Participating in it was an eye-opening experience, even though I had translated the Panchatantra 15 years prior. One study that grabbed my attention was by Johannes Niehoff-Panagiotidis about the Panchatantra’s translation into classical Greek during the Byzantine period in Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul). Byzantine scholars, we are told, were notoriously averse to translating foreign fiction into Greek, the language of the Bible and the classical tradition. An exception was made with regard to the Panchatantra, but the Greek translation was kept more as an icon at the emperor’s palace rather than as a version to be read by ordinary people.

Besides the translations and retellings, the Panchatantra had a profound influence on Arabic and European fable and narrative literature. The most notable are The Arabian Nights and the French Fables by La Fontaine, who states expressly that much of his material was derived from the Indian sage Pilpay, perhaps a corruption of the Sanskrit Vidyapati or Vajapayi.

Also read: When did large Hindu temples come into being? Not before 500 AD

How West adopted Panchatantra stories

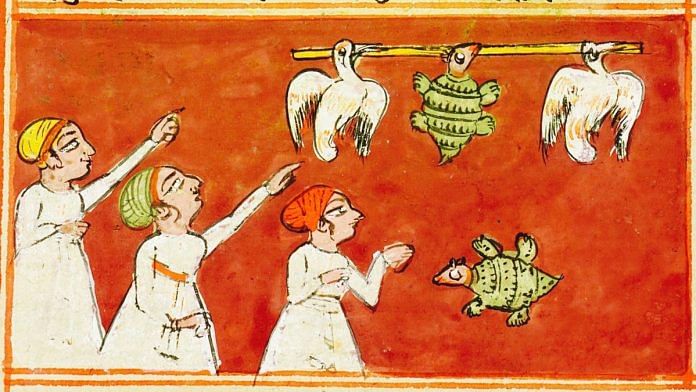

Panchatantra stories also became the subject of art. The Russian archaeological excavation in the city of Panjikent in Tajikistan (5th to 8th centuries CE) revealed several pictorial representations that the archaeologists identified as illustrations of Panchatantra tales.

Individual Panchatantra stories, furthermore, became transformed into Western folk tales, with unfamiliar animals being replaced by ones common in Europe. There is, for example, the beloved story of the Brahmin Devasharman and his pet mongoose, illustrating the peril of hasty action. Devasharman received a lucrative offer to officiate at a ritual for the king. There was a problem, however. Devasharman’s wife had gone to the river to bathe. Without anyone to look after his newborn son, he left him in the care of his mongoose. While returning home, the delighted mongoose ran ahead to meet his master with blood on his mouth.

The Brahmin, thinking the animal had eaten his son, beat it to death—only to find that the mongoose had killed a cobra that was trying to bite the infant. The Brahmin, mongoose, and cobra were transformed into knight, dog, and wolf in the Western retellings of the story. The most famous was the Welsh folktale of Prince Llewellyn and his dog Gelert. Here Gelert kills the wolf that was trying to attack Llewellyn’s child, and in turn, is killed by the prince thinking the dog with a bloody mouth had killed his son. This story gave rise to the common Welsh proverb about hasty action: ‘You will regret it like the man who killed his dog’.

The transformation of Panchatantra stories as they spread to different countries is instructive with respect to the ways in which cultures absorb foreign elements and make them their own—Devasharman became Llewellyn, and the mongoose became the dog Gelert. The world travels of the Panchatantra reveal how cultural objects are not narrowly “national” products but are open to being appropriated and enjoyed by people around the world. As we have Chinese and Tibetan Buddhism, so we have a Welsh Devasharman in Prince Llewellyn.

Further readings:

Patrick Olivelle, The Pañcatantra: The Book of India’s Folk Wisdom. Oxford World’s Classics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Chandra Rajan, Viṣṇu Śarma: The Pancatantra. Penguin Books: 1993.

Patrick Olivelle is Professor Emeritus of Asian Studies, The University of Texas at Austin. He is known for his work on early Indian religions, law, and statecraft. Views are personal.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)