Pakistan’s ongoing polycrisis, which has political, economic, and security dimensions, shows no signs of abating any time soon. Parliament dissolved weeks ago, and a new caretaker prime minister has taken charge, but there is no date yet for elections. To help move things, President Arif Alvi was expected to leverage his office and constitutional power to force the election commission to give a date. His letter to the Election Commission of Pakistan, however, was a damp squib.

Alvi’s argument that elections “should be held” by 6 November, did not do much to further the cause of the constitution in the country. In fact, his position that the election commission “may seek guidance from the Superior Judiciary for the announcement” of elections is nothing more than a copout that is likely to simply be ignored by the organisation mandated to hold timely elections as per constitutional norms in the country.

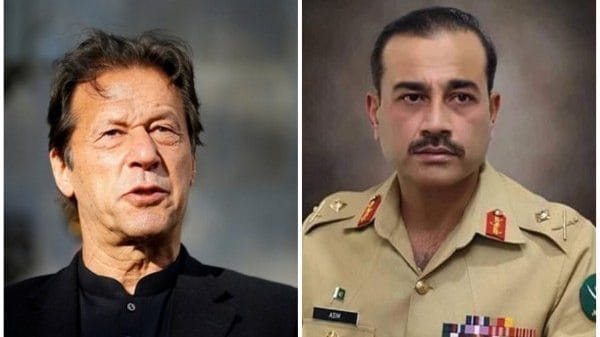

In a more normal country, there would be no argument about a key constitutional provision about the timeline for elections. But in Pakistan, bad faith actors have deployed creative interpretations of the constitution, backed by questionable actions, to subvert the will of the people. All of this seemingly to prevent the country’s most popular politician whose name must not be aired on mainstream media. Imran Khan – he who must not be named – is in prison. But as the polycrisis deepens and all sorts of tactics are deployed to cut down his party to size, his popularity continues to grow. Those at the helm of affairs believe that an economic recovery may lead the people to forget about him, but the reality is that the economic crisis is not ending any time soon.

The Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP), led by former president Asif Ali Zardari and his successor Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, has now started to play a good cop, bad cop routine. While the father signals that delays to the elections are acceptable, the son has publicly stated that he is not on the same page. In addition, the PPP is complaining about the lack of a level playing field, which is quite an interesting turn of events, given that it was part of a coalition that oversaw the decimation of Imran Khan and his Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI). It is even more interesting to see the party talk about the need for timely elections now, while it remained silent when the constitutional rights of the people of Punjab and Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa were usurped under its rule.

Also read: Pakistan president’s letter to expedite election is a paper tiger. He won’t upset the Army

The economy question

Amid this political crisis, Pakistan’s economy has continued to worsen. Proclamations about billions of dollars coming in from friendly countries like Saudi Arabia and UAE – over $50 billion by some accounts – are simply evidence of the delusions that occupy the minds of ruling elites in the country, particularly in Islamabad and Rawalpindi. Note that while the Saudi crown prince had time to stop over in Oman after his trip to New Delhi, he did not bother meeting leaders in Islamabad to announce any major economic deals with Pakistan, despite signals that he would be making a stopover.

On 14 September, Pakistan’s central bank surprised most economic analysts by not changing the key interest rate. Only 4 of the 41 economic analysts Bloomberg surveyed ahead of the announcement predicted that the rate would be left unchanged. The central bank’s explanation of its decision was nonsensical, to say the least. It is a clear signal that everything but rational economic policymaking is driving economic choices in the country. Everyone from the army chief to local intelligence officials and political leaders across party lines seem to believe that smuggling and hoarding are the primary drivers of the crisis, not runaway fiscal deficits caused by a sovereign refusing to mend its ways.

As a result, security officials have started showing up at the doorsteps of money changers to inquire what they are up to. The coercive nature of the state has scared off speculators, traders, and smugglers alike. But how long this lasts is anyone’s guess, especially when the fundamental drivers of the economic crisis remain unchanged. Information shared by the country’s central bank governor suggests that Pakistan needs another $8 billion in financing this fiscal year – which ends in June 2024 – just to meet its debt repayment requirements. How these inflows materialise when the sovereign is forcibly overvaluing its currency is a question few want to answer in Islamabad and Rawalpindi.

Also read: Nawaz Sharif is on his way back to Pakistan. But history shows he must prove his ‘piety’ first

Worsening security woes

As if the political and economic crises were not enough, Pakistan is also facing a worsening security crisis. Emboldened by the return of the Afghan Taliban in Kabul, the Pakistani Taliban have unleashed a wave of violence against Pakistan across the country’s northwest. At least four soldiers were killed just a few days ago in a battle in Chitral that went on for days. The Torkham crossing was closed in retaliation to this growing violence, leaving hundreds of trucks carrying goods stranded at the border.

Analysts monitoring the situation expect the situation to only worsen in the coming days as the Pakistani Taliban gain an even stronger foothold in the border regions. Just last Thursday, seven people were injured in Balochistan’s Mastung district in an attack targeting the JUI-F, a religious Islamic party that has historically been close to the Afghan Taliban.

Pakistan’s powerful military is facing multifaceted crises, and General Asim Munir must find a way to stabilise the situation soon. His advisors seem to have convinced him that administrative measures that curb smuggling and strengthen the rupee will stabilise the economy. This, in turn, the logic goes, will create space for him to manoeuvre a desirable outcome once elections are held (likely in early 2024).

The inflow of tens of billions of dollars from friendly countries will supposedly create a feel-good factor, lowering the anger among the general public. This strategy, however, is likely to fail – the central bank’s decision to hold the interest rate only reinforces this view. As a result, it is important for Pakistan’s most powerful man to seek more rational advice and either use what capital he has to pursue meaningful reforms or engage with political leaders across the board, including Imran Khan, to pave the way for timely, free, and fair elections in the country.

Uzair Younus is the director of Pakistan Initiative at the Atlantic Council. He tweets @uzairyounus. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prashant)