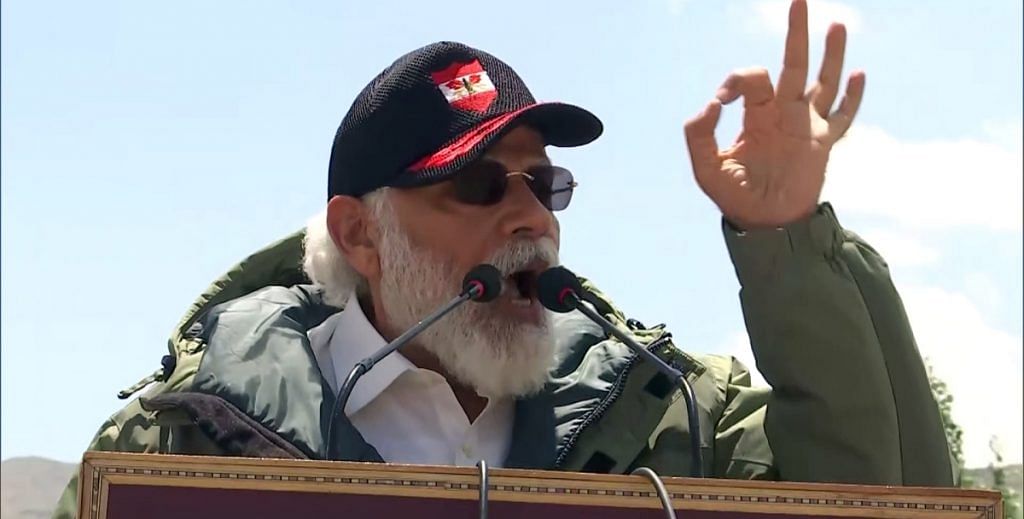

The juxtaposition of economic development and national security has been a staple item in Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s speeches on foreign policy. This came up again when he visited Indian troops in Ladakh. While sending a strong message against Chinese expansionism, he said that “today the world is devoted to development”.

This is similar to his other speeches, such as the one at the Shangri La Dialogue in 2018, in which he had contrasted cooperation with rivalry.

This binary of development and national security has been a standard assertion in Indian foreign policy strategy since the time of Jawaharlal Nehru.

Also read: Chinese threat is unlikely to go away. India needs big plans for LAC to save its land

Development or defence?

Of the many myths that populate India’s security policy thinking, none has been more enduring or as mistaken as the idea that domestic economic development can largely be a substitute for security policy. But while it was understandable during the vague welfare liberalism of previous Indian governments, it is surprising for a ‘nationalist’ like Modi. Nationalists tend to emphasise military power, and in some ways, BJP governments have reflected that association. Moreover, there is an intellectual basis for emphasising military power in Hindu nationalism, which makes this juxtaposition of security and development surprising, though scholars have noted that Modi has continued the traditional Indian emphasis on non-material power sources.

Security policy cannot be based on the hope or plans of long term economic development. Such thinking is based on the potentially fatal assumption that the country will face no unmanageable security challenges in the decades that it will take to become wealthy and strong. Unless there are other means of keeping security threats at bay in the meantime, or unless a country is extremely fortunate, this is a highly risky strategy.

The idea of development leading to security has adherents beyond politics, and within the Indian analytical community also. Leading commentator Pratap Bhanu Menta recently wrote, in the long run, development “is the only cornerstone of a defense policy”.

Also read: 1962 war was unavoidable. Goa liberation lulled India into false pride about military prowess

Lesson of 1962

India, in particular, should be wary of the pitfalls of such a strategy considering what happened in 1962. Nehru’s expectation that economic development would eventually take care of India’s security concerns did not consider what could happen in the interim. It was an expensive long-sightedness.

Sadly, not paying adequate attention to security ultimately undermined India’s developmental efforts. India had to hastily build its military capability in the 1960s, after the defeat at China’s hands. Such unplanned and rushed military spending disrupted India’s economic development efforts and set the country back significantly. The analogy may be old but still valid: spending on security is like insurance. If you balk at paying the premiums, you run the risk of paying considerably more in case of an emergency.

There were other consequences too. India’s loss in 1962 also diminished its global role. This was a role that was premised on India’s potential power, than on actual fact. The difference between potential and reality was brought home sharply to everybody after 1962. It would be another three decades before anyone talked about India seriously as a great power again.

The idea of security through development has an intuitive attractiveness — long-term economic development is indeed important for national power and security. Obviously, national power ultimately rests on wealth. Wealth permits a country not only to acquire instruments of military power, but also generate diplomatic influence. Both China and the US are good examples of countries that took on the mantle of great powerness after becoming wealthy. China’s influence today rests to a considerable degree on its economic clout.

Also read: Modi has chosen discretion on China because India’s real failure is in defence capabilities

India’s strained security policy

We see some parallels of Nehru’s logic again. Despite India’s worsening security situation, our security policy appears reluctant to come to grips with critical problems. This includes budgets, which are already low and are being further squeezed by pensions and personnel costs. There appears to be little thought being given about how to resolve this problem.

But it is much more than just budgets. For example, inadequate reforms mean continuing problems in areas such as civil-military relations, jointness, and defence acquisitions. Not surprisingly, India appears to wait for crisis to strike before it buys weapons: it has just ordered rifles for the army under the ‘fast track procedure’ and is also buying other equipment, including UAV, bombs and additional fighter planes. All of these obviously cost more when purchased in the teeth of an emergency, and are unlikely to help the actual crisis at hand.

The idea that economic development will take care of national security is particularly problematic in India’s environment. Although both the US and China were able to grow untested and become economic great powers before they became military powers, they are exceptions. The US had two oceans to keep other great powers at bay, while it developed.

China was also fortunate, in more ways than one. It was always stronger than its neighbours, but until recently, was not threatening enough to get Washington DC’s attention. China was also lucky because the 9/11 attacks and the Iraq war diverted US attention at a critical point.

Most countries, including India, are not so fortunate. Development may ultimately make India strong, but that is based on the risky assumption of calm seas during the crossing.

The author is a professor in International Politics at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), New Delhi. Views are personal.

Also read: Green tea to underpants, China’s grip on Indian lives goes beyond phone apps