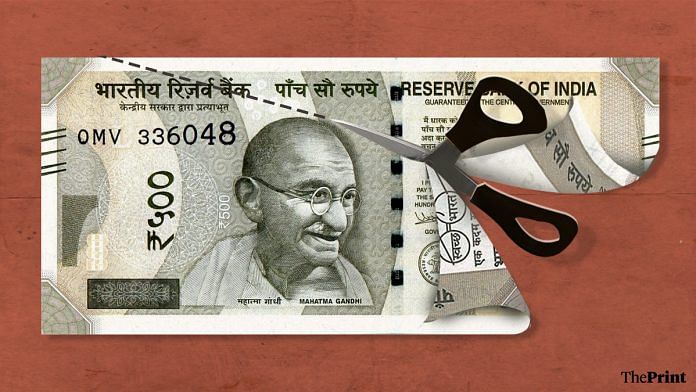

Much heat is being generated over the prices of petrol and diesel, primarily because central and state taxes account for about 60 per cent of the retail price. Even in inflation-adjusted terms, fuel prices have never been higher.

When the second OPEC-driven oil shock sent international oil prices past $30 per barrel (equivalent in today’s currency to about $100) in 1980, India’s petrol price was raised to ~Rs 5.10 per litre (today’s equivalent would be about ~Rs 80). It was no different in 2014; international oil prices had crossed $100, but India’s petrol price was a little over ~Rs 70. It is the opposite today only because excise on petrol has been trebled per litre, and that on diesel multiplied six-fold.

The government has benefited: central revenue from taxing petroleum products has multiplied more than five-fold in these last seven years. But there is a danger to such single-source revenue dependency; the high rates become visible and a subject of widespread debate, and you have no credible defence to offer for an effective tax burden of about 150 per cent. All that the government can do is to argue that it cannot afford to lower taxes because it would lose desperately-needed revenue. That much is obvious. Still, it can offer a partial solution: cap the tax load per litre of fuel. That would at least prevent more windfall tax gains if oil prices keep climbing.

There is a larger problem. This year’s Budget provides for central tax revenues to be 9.9 per cent of GDP. Before the Modi government took over, they were 10.1 per cent. Take away the surge in revenue from petroleum taxes and revenue would have fallen even further in relation to GDP. Admittedly, this reflects the impact of the pandemic, now in its 17th month of disruption. Consequently, revenue last year from goods and services tax was lower than in 2018-19, GST’s first full year of operation. This year should be better, because the staggered lockdown in May did not have the impact on revenue that the nationwide lockdown of 2020 did.

Also read: Cairn, Vodafone, Devas cases show India can’t treat outsiders like it treats its own people

Taking a leaf from the US and UK playbook

But there’s trouble round the bend: a year from now the states will run out of their five years of guaranteed 14 per cent annual GST revenue increase. Something major has to be done between now and then. Rates have to be rationalised, and the average GST rate has to be raised closer to the original intended level as soon as the current slump is over. This is over and above the commendable efforts to improve compliance, which seem to have borne some fruit.

In the interim, why not take a leaf out of the book of President Joe Biden in the US and Rishi Sunak, Britain’s finance minister? Both have raised taxes, either now or for the future.

Mr Biden has announced a major spending programme on infrastructure and payouts to poorer Americans. At the same time he has proposed to double the tax rate on capital gains, increase the income tax rate for the top tier, and raise corporate taxes — all of them taxes that are progressive in that they hit the rich, not the poor. Mr Sunak too has said he will raise corporate tax rates after the immediate economic slump is dealt with. Both Mr Biden and Mr Sunak have reversed the trend in their countries of steadily lowering rates. When the times change, policy has to adapt.

So why is New Delhi so determined to not raise rates on under-taxed forms of income and wealth, as a way of funding payouts to Covid’s economic victims?

It is the logical and indeed the obvious thing to do, and one does not have to be what Thomas Piketty calls the “Brahmin Left” (i.e. educated people who have moved from Right to Left) to say so. There is no other way to address the tax-GDP ratio and find money needed urgently for defence, health, education and infrastructure, without even more borrowing that would push up interest rates while taking the level of public debt to dangerous levels.

By special arrangement with Business Standard.

Also read: India needed a crisis to reform. It got one in 1991, thanks to Nehru & Indira’s Soviet model