A Dharmashastra text on display in the basilica of an Anglican Church in a premier European city? Most would dismiss such a claim as a joke or a hallucination. Yet, it is a fact. The city was London, the church, St. Paul’s Cathedral in the heart of that city and the display in question—an enormous statue of Sir William Jones.

Who was he? And how did all this come about?

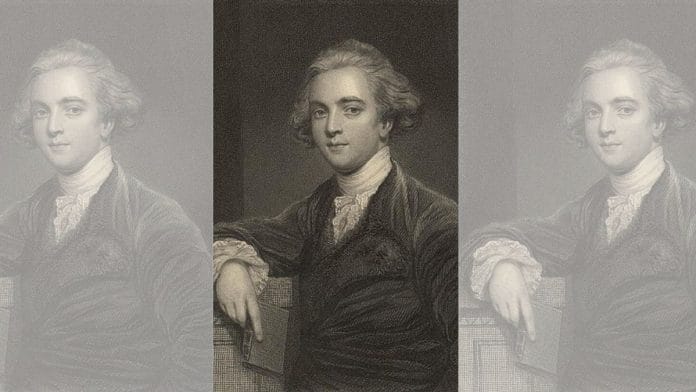

Before we unravel this strange contradiction, we need to know who Jones was since he was at the core of this astonishing paradox. William Jones (1746-1794), was a judge of the Supreme Court at Calcutta and a polyglot translator of Indian texts and laws. He played an instrumental role in setting up the Asiatic Society in Calcutta in 1784. During his time in India, he learned Sanskrit and Persian so that he could study the original sources himself. His Mohammedan Law of Inheritance was published in 1792 and Institutes of Hindu Law in 1796. He is best remembered today for his theory that several European and Asian languages like Sanskrit, Latin, Greek and Persian had sprung from a common root language (later known as Proto Indo-European). He was full of admiration for Sanskrit in particular:

“The Sanskrit language, whatever be its antiquity, is of a wonderful structure, more perfect than the Greek more copious than the Latin, and more exquisitely refined than either…”

The statue in St. Paul’s Cathedral

The carving of the Sanskrit text appears as part of a gigantic marble statue of Sir William Jones, sculpted by John Bacon and commissioned by the English East India Company. The statue is one of four large ones placed under the corners of the dome of St Paul’s Cathedral in London. The standing figure of Jones rests his hand on a book, which is his translation of the “Institutes” of Manu. Manu’s name (spelt “Menu” on the back of the book according to Jones’ peculiar scheme of transliteration) is written in the Devanagari script on the spine of the book.

There are more surprises to come. The pedestal where the statue stands portrays an intricate scene with elements from Indian mythology. The scene itself is revealed by two allegorical figures drawing back the drapes on either side. At the centre is a seated woman in a sari. In her left hand, she holds the Trimurti (a three-faced image of God in his three avatars as Brahma–the creator, Vishnu–the preserver and Shiva– the destroyer). With her right hand, she holds up a carved tablet depicting the scene of Samudra-Manthan (churning of the ocean).

Some of the treasures thrown up by the churning of the celestial ocean are carved in relief here as well—Airavat (Indra’s elephant mount), Kamdhenu (the divine cow that grants its owner any wish), Uchchaishravas (the seven horses who draw Surya’s chariot, depicted here as a single animal), the moon, and the containers of Halahal (poison) and Amrit (ambrosia). The churn, Mount Mandar, with Vasuki, the celestial serpent, as the rope, rests on the carapace of a giant tortoise (Vishnu’s Kurma avatar). The words, ‘Courma Avatar’ are inscribed above the scene. On top of the churn is seated a four-armed figure of Vishnu. American historian Thomas R. Trautmann, who has written extensively on late 18th-century British intellectual thought in relation to India, argues in his book Aryans and British India that this portrayal of images of Hindu deities in a Christian church is nothing short of unique.

Also read:

Christian Indomania

Trautmann stresses that if we wish to understand how such a sculpture found a place in a British church, we need to decipher its significance to the Anglicans (members of the Church of England) of Jones’ Day. Jones considered the first three incarnations of Vishnu (Matsya-fish, Kurma-tortoise and Varaha-boar) to be deeply connected to the biblical story of the universal flood. The Shatapatha Brahmana records how Manu was warned by a fish that a flood that would destroy the world was soon coming. Following the fish’s advice, Manu built a boat and when the deluge arrived, he was able to tie it to the fish’s horn and steer it to safety at the top of a mountain. The descendants of Manu (Manav–humans) once again populated the earth. The similarities between the story of Noah and the flood in the Bible are unmistakable.

For Jones, this story validated the biblical flood narrative and provided a sharp reply to rationalist disbelievers such as French author and philosopher M. de Voltaire.

We find further elaboration of these ideas in the writings of Thomas Maurice, an Anglican priest, scholar and an avid fan of Jones. In a pamphlet titled ‘Sanscreet Fragments, or Interesting Extracts from the Sacred Books of the Brahmins, On Subjects Important to the British Isles’, Maurice argued that the Trimurti or Hindu Trinity upheld the truth of the Christian doctrine of the Trinity (God the Father, God the Son, Jesus Christ and God the Holy Spirit). In his memoirs, he actually listed the remarkable similarities (in his view) between ancient Indian and biblical versions of the ancient past—creation of the world by a divine spirit that infused the ‘primordial waters of chaos’ with life; the fall of man; the future state of reward (heaven) and punishment (hell); a great deluge; the trinity; the incarnation of God in human form and the final destruction of the world in a fiery inferno.

Why were Jones and Maurice so keen to find similarities and links between ancient Indian and biblical narratives? Moreover, there must have been others who were just as enthusiastic about this, or else the Samudra Manthan scene with non-Christian religious imagery would never have been permitted space inside a basilica.

The answer lies in the time period in which they were writing. In the 1790s, the Christian church faced a severe challenge in revolutionary France. Scholars of the French Enlightenment – such as Voltaire, Jean-Sylvain Bailly and Constantin François de Chasseboeuf, Comte de Volney – had already criticised the overwhelming dominance of the Catholic church in the French state and society. Voltaire declared: “Every sensible man, every honourable man must hold the Christian sect in horror”. While many French people were devout Catholics, there was deep anger at the vast wealth of the upper clergy (who were mostly from the aristocracy) and the massive amount of land, power, and money held by the church in France. Between 1790-1795, the new revolutionary government in France passed a slew of laws curbing the power of the church, abolishing its privileges and confiscating its property.

It is here that Ancient India became the ‘debatable ground’ over which both warring sides laid claim. For Voltaire and the other Enlightenment sceptics, it offered an opening to a broader worldview and far deeper chronology than that provided by the Bible. Estimates based on the Bible placed the creation of the world around 4000 BCE while the cycle of the four Yugas (Satya, Treta, Dvapar and Kali) explained in the Manusmriti extends it much farther back in the past. Maurice, on his part, was determined not to let the sceptics ‘take over’ ancient Indian wisdom and inspired by Jones, wrote copiously to counter them (no less than seven volumes of Indian Antiquities published 1793-1800). For Enlightenment Christians like Jones and Maurice, the ancient Sanskrit narratives provided invaluable independent corroboration of biblical truths.

The Jones monument with Hindu religious imagery, therefore, was accommodated in a Christian church as independently validated proof of the truth of Christianity. Such an act would have been unimaginable before Jones and it became impossible afterwards, as the 19th century dawned and Indophobia unleashed by John Stuart Mill, Thomas Babington Macaulay and Charles Grant pulsated through British intellectual circles.

It was, as Trautmann put it, Christian Indomania’s brief moment.

Dr Krishnokoli Hazra teaches History at the undergraduate level in Kolkata. Views are personal.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)