A woman is either a mother or a wife—this was the commonly held view of women in most ancient societies, including India. In an earlier column, we met sage Yajnavalkya as he debated with the philosopher Gargi, an independent, intelligent, and self-confident woman who broke this mould.

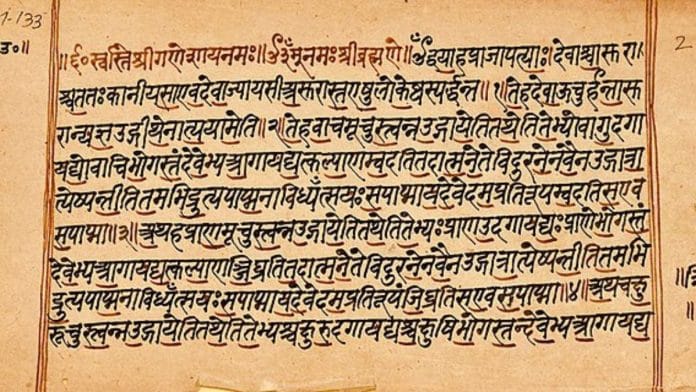

Here, I want to introduce you to two other women in another, more intimate Yajnavalkya episode. They are Maitreyi and Katyayani, the sage’s two wives. Interestingly, this story is repeated twice in the Brihadaranyaka, the oldest of the Upanishads, with many variants.

This Upanishad is preserved in two Vedic branches, Kanva and Madhyandina, each presenting somewhat different renderings. We are thus fortunate to have four different iterations of this story preserved in the tradition.

Wealth vs knowledge

Yajnavalkya is getting on in years and thinks he is going to die soon. Or, according to the other—probably later—version, he is thinking of becoming a wandering ascetic. In either case, he is about to depart from home. So, he wants to “make a settlement” between his two wives. He probably wants to bequeath to them sufficient financial resources so they can live comfortably after his departure.

At the outset, the narrator gives his assessment of the two women, offering a glimpse into how women may have been regarded during the time: “Of the two, Maitreyi was a woman who took part in philosophical discussions (brahmavadini—a philosopher like Gargi), while Katyayani’s understanding was limited to womanly matters.”

The last statement obviously reflects a patriarchal view, an ancient Indian version of the modern quip, “A woman’s place is in the kitchen.” We do not know about Katyayani’s response to her husband’s financial offering; she disappears for the rest of the narrative.

Maitreyi, on the other hand, has loftier aspirations; she wants something more than money. So, she asks her husband a probing question: “If I were to possess the entire world filled with wealth, would it, or would it not, make me amrita (immortal)?”

“No,” says Yajnavalkya, “it will only permit you to live the life of a wealthy person. Through wealth, one cannot expect immortality.”

Also read: Panchatantra had Hebrew, Spanish, Latin versions. Different cultures made it their own

Immortality within a woman’s reach

This is the first time in the literary history of ancient India that the word for “immortal” is used in its Sanskrit feminine form amṛtā, in reference to a woman. Maitreyi takes it as a given that a woman has the capacity to become immortal. If immortality here expresses the ultimate religious goal of the time—as it probably does—then that goal is not beyond the grasp of a woman.

Maitreyi then says with a hint of exasperation, “What is the point in getting something that will not make me immortal? Tell me instead all that you know.” Thus, Maitreyi anticipates her husband’s reply, recognising that knowledge procures immortality and that he possesses this knowledge.

In the earlier column, we saw Yajnavalkya engaging Gargi in a serious philosophical discussion as an equal. It appears that he was a man freed to some degree from patriarchal presuppositions and preoccupations, able to interact with women at an intellectual level.

In this episode, he is quite willing to engage his wife in one of the most significant and delightful conversations in the Upanishads. He is thrilled that his wife is willing to forego wealth for knowledge.

“You have always been very dear to me,” he says, “and now you have made yourself even more dear! Come, my lady, I will explain it to you.”

Also read: Actors of ancient India performed with ‘weapons, fire & poison’. Kautilya wasn’t a fan

The self vs the ultimate self

Yajnavalkya’s instruction is focused on atman or the ultimate self, possibly the most central theme in Upanishadic philosophy. In a nice literary twist, he picks up the term “dear” (priya) from his conversation with Maitreyi, using it as an entrée into the philosophy of atman:

One holds a husband dear, you see, not out of love for the husband; rather, it is out of love for oneself (atman) that one holds a husband dear. One holds a wife dear not out of love for the wife; rather, it is out of love for oneself that one holds a wife dear.

And it continues with reference to everything one holds dear—children, wealth, status, and so on. Indeed, one holds all of reality dear only out of love for the self.

A transition occurs here from “oneself” to the “ultimate self”, the passage seamless in the original Sanskrit, which uses the term atman for both. Yajnavalkya tells his wife:

You see, Maitreyi—it is one’s self which one should see and hear, and on which one should reflect and concentrate. For when one has seen and heard one’s self, when one has reflected and concentrated on one’s self, one knows this whole world.

He finally imparts the knowledge that procures immortality: “All this is nothing but this self.”

Yajnavalkya gives several examples to illustrate his philosophy of self, concluding: “This self is a single mass of cognition. It arises out of and together with these beings and disappears after them—so I say, after death there is no awareness (samjna).”

Maitreyi is dumbfounded by this last statement and bursts out, “Now, sir, you have utterly confused me! I cannot comprehend it at all.” No wonder. Yajnavalkya espouses an almost materialistic ideology of death—or it seems. This is not the knowledge that she expected. Maitreyi pushes Yajnavalkya to explain himself.

Also read: How Buddhists lost out to Brahmins in Nalanda. Even before the Turks came

The definition of immortality

“Look,” Yajnavalkya responds, “I haven’t said anything confusing.” When there is duality, then there can be a distinction between the seer and the seen. “When, however, everything has become one’s very self, then who is there for one to see and by what means? About this self (atman), one can only say ‘not–, not–’ (neti neti). By what means can one perceive the perceiver? That’s all there is to immortality.”

The ultimate self is beyond linguistic description. It can only be pointed to by using the negative method—not this, not that; it is not anything we may be able to name or define.

Such philosophical debates and stories like those of Gargi and Maitreyi open a small window into the lives of some women in ancient India—exceptional women who were not satisfied with the traditional role of wife/mother assigned to them. They aspired for much more than knowledge confined to “womanly matters”.

Eventually, large women-led movements within Buddhism and Jainism created monastic institutions for nuns where they could lead independent lives outside of patriarchal control. These were the earliest voluntary institutions for women outside of marriage in world history—institutions that survive to this day.

Patrick Olivelle is Professor Emeritus of Asian Studies at The University of Texas at Austin. He is known for his work on early Indian religions, law, and statecraft. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)

There are quite a few such instances in ancient India…but give at least a few such instances in Communist state who broke the mould of a comrade or a keep.