The grounding of Jet Airways India Ltd., the country’s oldest private-sector carrier, isn’t just bad news for customers and its 23,000 employees. It raises yet again a question that’s puzzled two successive governments and will continue to bedevil whichever party takes power after elections conclude next month: What’s killing capitalism in India?

Jet was born in the early 1990s, when India’s closed Soviet-style planned economy had just started embracing globalization and private enterprise. Back then, few Indians could afford to fly; now the country has the world’s fastest-growing aviation market. An airline that was at one point the industry’s dominant player should theoretically have been able to thrive.

While Jet’s costs were too high compared with those of its no-frills rivals, that issue could have been fixed. The real problem is that Jet founder Naresh Goyal gambled away a perfectly fine – albeit, unprofitable – airline by not injecting equity himself into the cash-strapped business, or stepping aside in time and allowing someone else to do so.

It’s only natural for entrepreneurs to be possessive and irrational, especially when – like Goyal – they’ve been so wildly successful for so long. The bigger conundrum is why providers of outside capital (banks and capital markets) didn’t act as a disciplining force on Goyal and save the business.

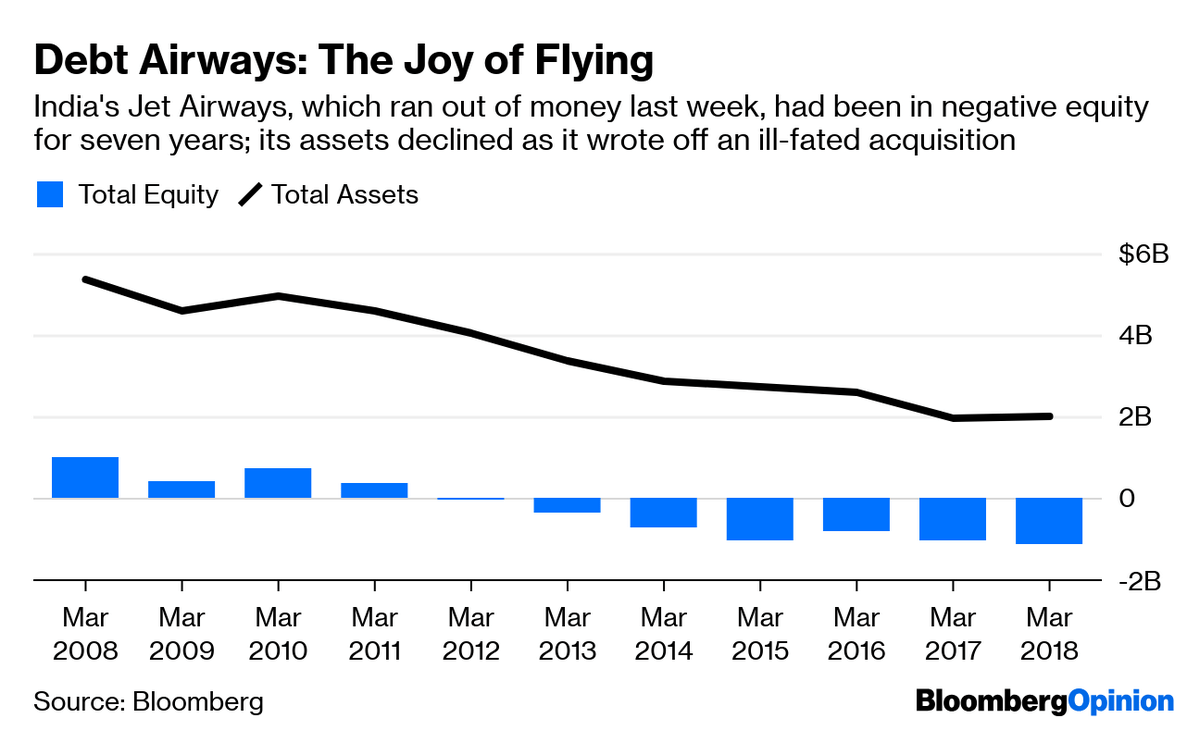

Despite Abu Dhabi’s Etihad Airways PJSC taking a 24 percent stake in the airline in 2013, Jet has been slipping deeper into negative equity for seven years. Had India’s state-run banks insisted on a timely and substantial capital infusion, and had they credibly threatened to dilute Goyal’s 51 percent controlling stake by issuing themselves new shares when the inevitable debt default occurred, Jet would now be flying under a new owner.

When Jet’s rival Kingfisher Airlines Ltd. collapsed in 2012, India didn’t have a modern bankruptcy law. Now it does. Even so, in Jet’s case – or in the high-profile $7 billion insolvency of tycoon Anil Ambani’s Reliance Communications Ltd. – creditors didn’t utilize that option. Instead they foolishly relied on entrenched insiders to make things right, thereby hurting their prospect of extracting value.

Also read: Air fares spike, staff protest as grounded Jet Airways takes a toll

Banks are now awaiting a white knight. Yet for a new owner to revive the airline after it has stopped flying will necessarily mean very deep haircuts on its $1 billion of net debt. State-run lenders will lose heavily, as will employees. It’s an unnecessary waste of capital and jobs in a country that doesn’t have enough of either.

So what’s to be done? Private investment in India has been weak for years now, first under a Congress Party-led coalition and then under Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party. There has been no dearth of new rules in this period. But rules-based capitalism cannot flourish in a business landscape so heavily dominated by insiders, who are regularly tapped by all parties for anonymous political donations.

For real change to occur, electoral financing must be overhauled and market forces strengthened so that company founders, at least in capital-intensive industries, aren’t allowed to hang around and become a risk to viability.

Almost every large business failure in India today involves providers of outside capital – and their agents – giving insiders a free pass to maintain control using other people’s money, destroying value in the process. These agents aren’t just company boards. In the case of the now-bankrupt infrastructure financier-operator IL&FS Group, it was the auditors and credit rating agencies that led even small pension plans like that of the American Embassy School staff in New Delhi into trouble.

Or consider the problems brewing in India’s mutual funds industry, which lent money to media mogul Subhash Chandra against his shareholding in Zee Entertainment Enterprises Ltd., a highly profitable television content business that dates back – once again – to the early days of India’s economic liberalization. When Chandra’s leveraged bets on infrastructure ran into liquidity problems, the mutual funds agreed not to sell the Zee shares they held as collateral.

The fund managers now have the chutzpah to tell investors that the net asset value for their maturing plans isn’t available in full – and won’t be until Chandra can find a buyer for Zee. Even more shockingly, the bilateral loans to Chandra, masquerading as bonds, are still rated A.

Relationship lending is to be expected in a state-dominated banking system prone to rigging by crony capitalists. But relationship-based fund management? That shows the extent to which even the private sector is compromised. Business “promoters,” as they’re known in Indian law, have used a mix of personality cult and proximity to political power to terrorize the ultimate providers of outside capital.

It’s lamentable that after 14 years as a publicly traded firm, operating in a capital-intensive, price-sensitive, competitive, regulated industry, Jet was still allowed to carry on basically as Goyal’s fief. Let the airline’s avoidable collapse serve as a warning for the next government: Don’t go out of the way to rescue Jet, but do save Indian capitalism from insiders.

Also read: Jet airways waits for a buyer as rivals muscle in on territory

Andy Mukherjee is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies and financial services. He previously was a columnist for Reuters Breakingviews. He has also worked for the Straits Times, ET NOW and Bloomberg News.

Only the very naive will believe that the intersection between business and government takes place only during elections and the exchange of courtesies is limited to funding required to fight an election. It is an all weather relationship. Consider a group like Videocon, associated for a long time with consumer electronics. Plot how swiftly it piled up loans after 2008. Not limited to PSBs, it now appears. No PSB Board, much less the operating levels that deal with borrowers, could have sanctioned loans icon that colossal scale. The group has some valuable oil assets abroad whose disposal may allow it to clear a major part of its principal. Other larger borrowers like ADAG may have fewer worthwhile assets to sell. The music has been playing for a long time, and no new government has felt the need to stop it. It is just that the gas tank is now empty. Fundamental changes, not just in how capitalists operate but also in how governments manage this part of the political economy, are becoming necessary.