The chariot of history, to use a well-known classical Indian imagery, is driven by the Lord who creates outstanding leaders in every area of human activity to man it, and to carry out His mandate in this world.

This is why the surest way to malign a nation’s history is to defame the class of its leading lights – the heroes and heroines who once commanded the nation’s love and respect by their sheer capacity to make sacrifices for cultural and political emancipation. Accuse them of deceit, hubris, chauvinism, and treachery – thus making villains out of heroes, and, et voila! You have succeeded in turning the historical perception of a people upside down.

The historians of the Left understand this very well. They have liberally used this device to mutilate the historical perception of the Indian people – especially targeting its educated section – in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, almost reversing their opinion on what has been a glorious revolution inaugurating mass participation in India’s movement for Swaraj, i.e., freedom, from a millennia-long colonial occupation of its political and cultural spaces.

It is a remarkable achievement of the historians of the Left in India that they have succeeded in cultivating among the educated Indians—from the 1970s onwards—an indifferent and often cynical attitude toward the early 20th-century revolutionary nationalist leaders who spearheaded the Swadeshi movement of 1903–1908, and the cherished ideals of that movement. The credit for this primarily goes to their prolific historiographical writings on the subject of the Swadeshi movement in particular, and on modern Indian nationalism in general.

In such writings, modern Indian nationalism – which germinated during the radically transformative 19th-century epoch of Indian history popularly known as the ‘Bengal Renaissance’ (also called the ‘Indian Renaissance’), and which steadily grew to assume a distinctly revolutionary character by the turn of the century – has itself been equated with monstrous 20th-century Western European ideologies like Nazism. Such comparisons diluted the ideas and ideals that defined Indian nationalism, making a significant section of present-day Indians wary of its influence on contemporary culture and politics.

Also read: The how and why of antisemitism on American campuses

Pioneers of Indian historiography

The history of a people is not merely a decade-by-decade or period-by-period chronological account of their past generations’ lives, political and cultural. It is a narrative that tells their story in an inspiring manner and provides them with a binding force that imbues them with a palpable love for their home country and a sense of common purpose with regard to the country’s welfare and progress. In other words, the history of a nation is its lifeblood, an indispensable part of her people’s education and preparation for their life that gives the nation its strength and vitality.

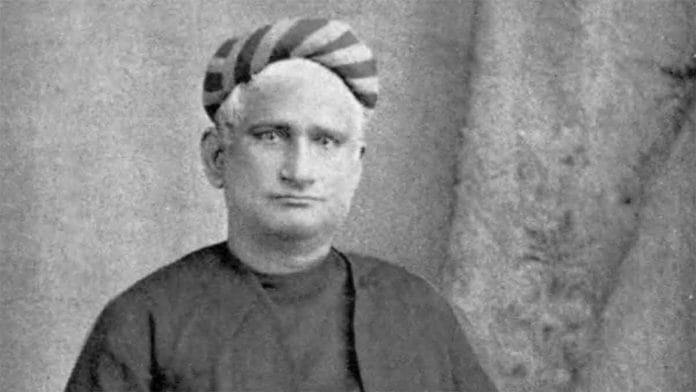

It is the national history that can help a people determine, during peacetime as well as in times of war, the overall direction or course that the nation should follow into the future. This compass-like function and vision of national history were powerfully articulated by the leaders of the Swadeshi movement – most prominently in the writings and speeches by Rabindranath Tagore and Sri Aurobindo in the early 1900s. Both built upon a similar exercise initiated in the late 19th century by Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay, who pioneered the writing of history from a nationalist perspective and upheld rationalism.

Chattopadhyay restated Hinduism in a modern philosophical idiom – in the language of Comtean Positivism – which appealed to the educated youth of Bengal. His prolific writings –historical essays, novels, dramatic dialogues on philosophy and religion, and humorous sketches satirising political and social issues – came out in the journals Bangadarshan and Prachaar, which Chattopadhyay edited and published himself. These writings captured the imagination of the Bengali youth. The high point of this literary phenomenon was the serialised publication of his fiercely nationalistic novel Anandamath between 1881 and 1882. The novel contained the Vande Mataram song.

Chattopadhyay’s influence extended beyond literature, as he also played a significant role in shaping the cultural identity of Bengal. His works resonated with the sentiments of the Bengali people, much like the discussions surrounding Bengali nationalism that emerged during the tumultuous times of the 20th century.

The nationalist historian RC Majumdar observed that no other Bengali book, or any book in any other language, had inspired the Bengali youth so profoundly. In addition to it, Chattopadhyay’s Kamalakanter Daptar (1875), Dharma Tattva (1888), Krishna Charitra (1886), Devi Chaudhurani (1884), Rajasimha (1882), and Sitaram (1887) also deeply influenced the Bengali readership to think and feel for their motherland, India, from a nationalist point of view.

Chattopadhyay passed away in 1894. About three years before that, Swami Vivekananda—who was then peregrinating all over the Indian Subcontinent—spoke emphatically about the necessity of awakening the “true national spirit” before a gathering of students in Alwar, Rajputana. Vivekananda entreated the young members of his audience to prepare themselves for the task of writing Indian history from an Indian perspective. This history, Vivekananda asserted, would become the cornerstone of a “national education”. A decade after Vivekananda’s outspoken advocacy predicated on nationalist historiography, Rabindranath Tagore, in his 1902 essay titled “Bharatbarsher Itihas” (lit. Indian History), reiterated the same in unequivocal terms.

Around this time, educator and philosopher Acharya Satish Chandra Mukherjee founded the Dawn Society to promulgate nationalist thought. By highlighting Indian intellectual heritage through the society’s regular classes and seminars, Mukherjee campaigned for self-reliance and constructive work (‘Atmanirbharta’ in today’s parlance), not only in the field of education but all areas of human activity, with an Indian approach. His efforts culminated in organising the National Council of Education and—as a concrete result of it—the Bengal National College. Together with the Saraswat Ayatan of Brahmabandhab Upadhyay, Tagore’s Brahmacharya Ashram in Bolpur, and Taraknath Palit’s Society for the Promotion of Technical Education, the National College became a tangible accomplishment of the movement for national or Swadeshi education.

A few years after Tagore’s endorsement of proliferating national education through a national history, Sri Aurobindo (then known as Aurobindo Ghose) – who had been following Chattopadhyay’s works and had written extensively on the master of Bengali novel between 1893 and 1894 – began spreading the idea of national education across the country. Closely associated with the activities of nationalist thinkers and leaders like Bipin Chandra Pal, Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Sister Nivedita, Tagore, and Satish Chandra during the Swadeshi movement, Aurobindo became involved in the project of national education from early on. When Aurobindo moved to Calcutta in 1906, having left his job in the Princely State of Baroda, he joined the newly founded Bengal National College as its first principal. He elaborated on the nature and goal of the programme through numerous speeches and writings between 1906 and 1909.

Also read: Modi’s India is coming into its own. Moon landing and G20 Delhi Declaration are just the beginning

Indian Renaissance 2.0

Stimulated by the writings and speeches of Vivekananda, Tagore and Aurobindo, a crop of nationalist scholars and writers emerged in the initial decades of the 20th century. Among them were historians Radha Kumud Mukherjee, Rakhal Das Banerji, Benoy Kumar Sarkar, Jadunath Sarkar, RC Majumdar, Hem Chandra Raychaudhuri and Kalikinkar Datta. These writers presented Indian history and sociology from a fresh perspective and established humanities research in India on firm grounds.

However, from the 1970s onwards, their works in historiography and sociology were sidelined by systematically denouncing them with labels like “historians of the Bhadralok class”. They were called authors who “romanticise militant nationalism” and are “fascinated with” the acts of “individual terrorism”. Thus, the entire programme of revolutionary nationalism in India, initiated by the well-organised Swadeshi movement of 1903-1908 with an illustrious history spanning the first four decades of the 20th century, was trivialised as a mere “cult of individual violence”—a phrase coined by Sumit Sarkar, a prominent historian of the Left. Consequently, nationalist historiography has been practically absent from the consciousness of the educated Indian of the 21st century.

It is imperative for young and budding Indian historians of our times to once again concentrate their focus on retrieving the nationalist perspective of Indian history. This is especially crucial to provide proper direction, substance, and robustness to the Indian Renaissance 2.0 – which we have been witnessing since the beginning of the current century. The chariot of history rolls forward, whipped on by the great driver – it is for a new generation of historians who would tell the story of India from a keenly Indian perspective to heed the calls of His conch shell.

Sreejit Datta is an educator, researcher and social commentator, writing and speaking on subjects critical to rediscovering and rekindling the Indic consciousness in a postmodern, neoliberal world. Sreejit is a recipient of the Rajeev Circle Scholars Fellowship for History, as part of which he is writing a book on the revolutionary nationalist aspect of India’s Freedom Struggle. He currently teaches at UID, Karnavati University in Gandhinagar, Gujarat.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)